An unfinished lament for Margery McGregor

An unfinished lament for Margery McGregor

I think of your crisp blue eyes and wispy white hair That framed your face like a penumbra of snow I remember the night before you died and I sat On the floor by your bed holding your hand I think I never was as close to you as then, so connected Although we didn’t speak and I knew that the end was near I felt you like a little girl wanting to give up and trust What was not in your nature to trust And just be there and slowly not be there You who loved to be in touch and free and felt so deeply But showed so little out of consideration. Lying on that high bed with the trees hiding the moon and the stars as the night went on And you didn’t say a word. The window at my back was cool And Dad snoring quietly in the bed next to your all unknowing And not ready to let you go and not knowing that he had no choice. How dependent he was on you. The bed lightly covered with the pinkish knitted blanket you loved so much And that had been with you through so many years Over your feet the crocheted cover from one of your sisters I think And the pillows downy and soft just as you liked them. I just held your hand all through the dark and lightening hours Dad got up to shave and I noticed your breathing getting lighter and lighter Until I knew it was time to call him All he could say was “How will I live without you?” And I knew that was literally true for all that he lived For another twelve years it was not really life He had relied on you too much to give him The sense of connection and place. And the dahlias and vygies[1] you loved so much Are less bright and there is no marmalade bubbling on the stove With bees being nuisances – Life is less rich.

What about the roads you longed to travel and didn’t? What kept you from going there? How did you feel about not Seeing all the places you had wanted to see? So a symphony will not be written for you nor will your voice Rise in song nor speak lovingly and wisely again. But what a symphony sounds in my ears for you And ends always on that melancholic Celtic chord. I miss those hands so business-like and loving That held me back and pushed me forward.

[1] Vygies are very colourful, small, succulent flowers in the mesembryanthemum family which are endemic to the somewhat arid west coast of South Africa.

Unfulfilled desires

My mother Margery was born on 28 December 1907 and died on the last day of December 1986, a little more than a year after she and my father Murray had celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

My mother Margery was born on 28 December 1907 and died on the last day of December 1986, a little more than a year after she and my father Murray had celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

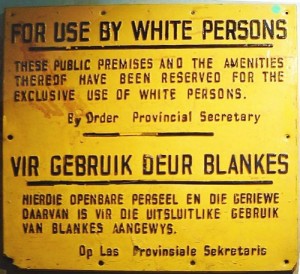

She was the daughter of a pharmacist who came to South Africa from the United Kingdom and settled with his family first in Oudtshoorn in the Karroo and then in the small city of George, also in the Western Cape. She was one of five sisters.

The piece above I wrote a few years ago, just after my father died, but have never been able to finish or polish it.

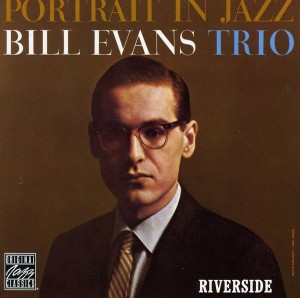

My brother Chris was a great musician who lived in France. He came back to visit our father when our mother died. He told me he had always wanted to write a symphony for her, but that he feared no-one would want to play it.

Chris himself died in France at the age of 53 on 26 May 1990, coincidentally our father’s 82nd birthday.

Mother had always had a sort of wanderlust, a desire to move and explore, in contrast to our father’s desire for stability and routine.

Mother’s dream was, when my father retired, to sell all their possessions, buy a caravan, and hit the road! Dad on the other hand wanted his books around him, and teas regularly at 11.00 a.m. and 4.00 p.m.!

So mother threw herself into things like gardening, cooking (especially jamming) and looking after things. When we lived in Blythswood she kept cows, made butter and cheese, explored natural remedies and folk medicine.

I have these great memories of her in the kitchen with huge pots of bubbling jams on the wood stove, bees buzzing around them and sometimes falling into the hot sugary geysers, while outside the garden hummed with colour and energy, flowers and vegetables flourishing from the compost she made.

I have these great memories of her in the kitchen with huge pots of bubbling jams on the wood stove, bees buzzing around them and sometimes falling into the hot sugary geysers, while outside the garden hummed with colour and energy, flowers and vegetables flourishing from the compost she made.

Even when she became very ill with the cancer that finally killed her she wouldn’t give in, wouldn’t acknowledge that she was suffering, so I don’t think Dad was even aware of how serious it was, how close to death she was.

Mother died without doing the travelling she yearned to do. I always feel very sad when I think about that.

So I guess this piece is all about unfulfilled desires – for a life of adventure and travel, a symphony and a poetic tribute. And life goes on for all that. We get past the Celtic chord and move on, leaving a bit of our hearts someplace, but finding new lives, new connections.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2012