“If you can’t see the country’s past, if you can’t hear the voices from the past then you can’t understand the present.” – Anglican priest Michael Weeder, quoted in Mike Nicol’s Sea-Mountain, Fire City (Kwela Books, 2001).

“On its own the passage of time neither heals injustices nor pacifies antagonists.” – Bernard F. Connor OP, The Difficult Traverse (Cluster Publications, 1998).

When ANC Youth League president Julius Malema made his now-infamous statement that “all whites are criminals”, in reference to what he termed the “theft” of land by whites from blacks, the response of most whites was defensive – taking the form of either an aggressive denial or a personal attack on Malema himself.

While understandable, these responses are not helpful, and also show a very basic misunderstanding of the history of this complex country. Perhaps such misunderstanding is not surprising, given the many years of racist propaganda to which many whites have been subject for so long.

Certainly Malema’s statement was calculated – and he is too clever a politician not to have calculated this – to excite his followers and to provoke his white opponents. He certainly succeeded in achieving both those outcomes, though his very success raises many other questions.

The most basic question is, what sort of South Africa do we want? And how do we want, in this envisaged country, to relate to our past? We need to ask these questions, and to begin to search for answers, before we can move on, because we will not be able to move on until our relation to our past is clarified. The experiences of Northern Ireland, the former Yugoslavia, Chile, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, Argentina and even the United States, attest to this, as indeed do the responses to Malema’s statement.

Lithuanian philosopher Emmanuel Levinas who lived through a time of unparalleled violence against his fellow-Jews wrote:

“Violence does not consist so much in injuring and annihilating persons as in interrupting their continuity, making them play roles in which they no longer recognise themselves, making them betray not only commitments but their own substance, making them carry out actions that will destroy every possibility of action.”

Police supoervise the destruction of Modderdam on the Cape Flats, August 1977. Image from "A Shanty Town in South Africa" by Andrew Silk, 1981.

South Africa has certainly experienced much of this type of violence in the more than 500 years of white intrusion onto the soil of this southern tip of the great continent.

The first violence in this intrusion took place in 1487 when Portuguese sea captain Bartolomeu Días, using his cross-bow, shot and killed a black African at the place he called São Bras, which we now call Mossel Bay.

In the light of the later propaganda about who was here first, it is perhaps relevant to note that the people who were seen on that fateful shore in 1487 were “blacks, with woolly hair like those of Guinea” – i.e. most likely Bantu-speaking people and not Khoisan, indicating that the apartheid discourse that whites moved into empty land when moving east from the Cape Colony and that the Bantu-speaking people arrived there at about the same time was a lie.

Emblem of the Dutch East India Company carved above the entrance to Cape Town Castle Circa 1680. Photo by Andrew Massyn via Wikipedia

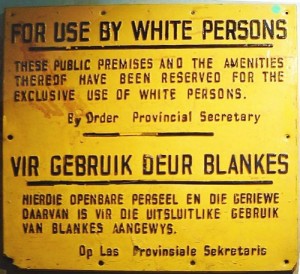

When the Dutch arrived at the Cape and started to develop their replenishment station below Table Mountain in 1652 they found Khoikhoi people already in residence there and began systematically to displace them. The first “apartheid” barrier was the almond hedge planted by Jan van Riebeeck to keep the Khoikhoi out of the Dutch East India Company’s gardens growing on land that the Khoikhoi had for generations considered “theirs”. This was perhaps the first “land grab without compensation” in South Africa’s history. The first, but by no means the last.

The planting of the Dutch settlement at the Cape was also a grave interruption of the continuity of the indigenous people. It interrupted the continuity of the grazing of their cattle; it interrupted their freedom of movement across the land and interrupted the natural power relations between groups by introducing outside influences.

The very beginning of what we now call South Africa was steeped in violence and the voices of those who suffered need to be heard, even at the distance across time of more than 500 years, as do those who suffered after.

We all in South Africa at the beginning of the 21st Century need to open our ears to those voices which call to us down the centuries, those voices which, if we are still and listen, we might hear carried on the winds which blow down the crevasses and kloofs of Hoerikwaggo (or Sea-Mountain, as Table Mountain was called by the Khoikhoi), or in the hot winds of the Karoo or the gales across the Highveld, the songs and laments of Khoisan, of slaves, of Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Tswana. We might, if we listen carefully, also hear the cries of children and women and old people trekking through the unknown, fearful and tired.

History, it has been said, is always written by the victorious. In Africa we also have a saying, that until the lion tells his story, the hunter is always the hero.

And so I think we have to re-imagine our history. We have to use our minds’ eyes to see how people have lived and died, and begin to re-interpret the meaning of that living and dying. We have to try to imagine what it must have been like for those people on the shore at São Bras to have seen these strangers arrive, and to have seen one of their own killed by this hither-to unknown weapon.

It is important too that we try to understand the feelings of Khoikhoi at the Cape when Van Riebeeck planted the Dutch flag (or was it the flag of the Dutch East India Company?) on their soil. And the fears of the Dutchmen who were given the task of making the Cape a viable investment for that company – what were their feelings about being stuck in this strange land, surrounded by people who were so different?

Ven. Michael Weeder, now Dean of St George's Cathedral, Cape Town. Image from http://cape-slavery-heritage.iblog.co.za/2011/01/12/people%E2%80%99s-dean-cadre-padre-father-michael-weeder-named-new-dean-of-st-georges-cathedral/

To quote Michael Weeder again (from Nicol’s book) talking about the Slave Tree monument in Cape Town: “Families were destroyed here. Children sold to one person, their mothers sold to another. A woman sold to a farmer in Stellenbosch, her man sold to a merchant in Cape Town. Can you Imagine that? Can you just imagine what it was like, all the misery that happened here on the ground beneath our feet?”

Can you imagine how the great chief Maqoma felt, lying on the ground with the booted foot of that hyperactive Governor of the Cape Harry Smith on his neck?

Can you imagine the pain of a young mother dumped with her little children in the veld at Dimbaza in the middle of winter?

Can you imagine the anguish of a father watching the home he had painstakingly built for his family at Modderdam or Crossroads being demolished?

Can you imagine how a descendent of Sekwati (chief of the Pedi at the time of the Great Trek) must feel every time he or she sees the Voortrekker Monument?

South Africa is a complex country with a rich history which, like all histories, is an interpretation of what we have been taught, what we have read, what we have experienced. No one history or interpretation of history, can adequately do justice to where we are today in this country.

If we are to make something of this country, we need to listen and understand each other, and that takes patience and a willingness to learn. A willingness, a humility, to allow another person’s history, in a sense, to become my own.

Of course we cannot change the past – what has happened has happened. There can be no turning back of the clock – indeed to which time would we turn it? But we have to deal with the past some creative way without denying anything in it. As Beyers Naude said, “No healing is possible without reconciliation, and no reconciliation is possible without justice, and no justice is possible without some form of genuine restitution.”

In the Interim Constitution, which was the basis for the elections of 1994 and the subsequent Government of National Unity, a statement about reconciliation was included which might be a basis for our moving forward. The Interim Constitution spoke of the “need for understanding but not for vengeance; a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for ubuntu but not for victimisation.”

In the Preamble to the Freedom Charter is the statement “that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people.”

In his recent speech at Stellenbosch, which has aroused the fury of so many whites, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu said:

“Our white fellow citizens have to accept the obvious: You all benefited from apartheid. But that does not mean that all are responsible for apartheid.

“Your children could go to good schools. You lived in smart neighbourhoods. Yet so many of my fellow white citizens become upset when you mention this. Why? Some are crippled by shame and guilt and respond with self-justification or indifference. Both attitudes make that we are less than we can be.”

We are all here now and belong here simply because we are here. There is absolutely no profit for any of us in self-justification or indifference.

To make our future together we have to let go of guilt and let go of the need to justify any of the evils of the past. We have to understand where we come from by hearing those voices from the past and make active efforts to change ourselves, to, in Gandhi’s famous words, “be the change we want to see.”

We defeat ourselves if we wallow in guilt or recrimination, or, with indifference, wait for the passage of time to heal the many injustices and antagonisms that have arisen in the course of our complex, rich and fascinating history.

We can be so much more.

© Text and photos, unless otherwise indicated, copyright by Tony McGregor 2011

How can whites live with the legacy of apartheid? – a moral question

Prison wall on Robben Island. Photo by Tony McGregor

South Africa has always been, in Allan Drury’s words, “A very strange society” so it should perhaps not surprise us that 20 or so years after the official death of apartheid, that strangeness still afflicts us so severely. Drury wrote his book in 1967, when official apartheid was just 20 years old. Since then the strangeness has only grown.

The 1994 settlement which saw beloved elder statesman Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela become the first democratically-elected president in our twisted history, was heralded by many as a “miracle” – and there was much that seemed miraculous. For the first time that I know of in history a ruling oligarchy negotiated itself out of power.

But that miracle had some serious flaws, flaws which are more and more coming to light as the strains of adjusting to a globalised economy and a rapidly-evolving world political scene start to take hold. The very fact that the settlement was negotiated has left us with issues that need to be resolved. Negotiation is frequently, though not necessarily always, done through compromise and letting go of interests.

Negotiations took place in the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) and the subsequent bi-lateral negotiations between the ruling National Party of President F.W. De Klerk and Mandela’s African National Congress, and then in the broader Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF) which hammered out an interim constitution for the country. In all these negotiations some critical issues were left to the future, one of them, the issue of land distribution which was greatly in favour of whites thanks to the 1913 Land Act which had made 87% of the land surface of South Africa an exclusively white preserve.

The MPNF left land tenure issues to be resolved by the so-called “willing buyer, willing seller” mechanism. By 2008 this policy had failed to resolve the land tenure issue satisfactorily and, according to Professor Ben Cousins of the University of the Western Cape, more people have lost access to land than have gained it through this mechanism. As Prof Cousins points out: “If land questions remain unresolved, the possibility clearly exists for populist politicians to focus strongly on these issues in order to build a support base, leading to unrealistic policies that promise much but fail to deliver real benefits. This in turn could lead to discontent and unrest.” (On the “Livelihoods after land reform” site, http://www.lalr.org.za/ accessed on 21 August 2011).

It is this discontent and unrest that is very visible in South Africa today, and is articulated very vividly by the former president of the ANC Youth League Julius Malema, who not long ago called whites “criminals” because they stole the land from the blacks. “They (whites) have turned our land into game farms… The willing-buyer, willing-seller (system) has failed,” Malema was reported as saying. “We must take the land without paying. They took our land without paying. Once we agree they stole our land, we can agree they are criminals and must be treated as such.” Many whites responded to these statements with defensiveness which, while understandable , showed but little historical insight.

Solomon T. Plaatje

In fact much of the land was taken by force and, in 1913, by law, when the infamous Land Act was first promulgated by the Parliament of the newly-formed Union of South Africa. This Act made a black South African, in the words of contemporary writer Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje “… not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.” That perception of pariah status reached its apogee during the apartheid era and has continued to some extent up to the present.

A disturbing result of the demise of official apartheid has been the rise of white denial of the distress caused by apartheid – the rise of people who would argue that apartheid was not that bad, that blacks under apartheid were better off than blacks in the rest of Africa, and even, to some extent, than blacks in other parts of the world, for instance, the United States.

The other side of this denialism is that the same critics use the undeniable corruption that is plaguing South Africa to discredit the ANC government and imply that blacks cannot be trusted or are naturally prone to corruption and are un-skilled or other such racist inferences.

Philosopher Samantha Rice from Rhodes University in Grahamstown asked in a recent (2009, Journal of Social Philosophy) article, “How do I live in this strange place?” Rice points out that “…an honest and sincere public dialogue about race has not yet happened in South Africa—the subject is too close to the bone for many and too much is at stake and too confused—race is the unacknowledged elephant in the room that affects pretty much everything, in and outside academia”

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu. Photo by Tony McGregor

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu recently caused some more concern among whites when he raised the issue of reparations for blacks who had suffered under apartheid – remarks which, not for the first time, caused some to call him racist. Tutu has consistently argued for more moral dialogue, for a greater commitment from whites to engage with their black fellow-citizens about issues which concern both. Tutu, however, is articulating, in more reasoned tones, to be sure, what Julius Malema is also saying – for the vast mass of blacks have up to now experienced little improvement while whites continue to live much as they did under apartheid. Whites continue to live in white areas, their children go to well-resourced schools, they have regular holidays and participate in many cultural activities. Most of these things are denied to blacks.

Now of course there is the class issue – but in South Africa class and race coincide to a very large degree and whites are seemingly in the main so habituated to privilege that they don’t see themselves as privileged, and hence the denialism, the refusal to engage in the debate but rather to minimise the negative effects of apartheid. As Rice noted, “Because of the brute facts of birth, few white people, however well-meaning and morally conscientious, will escape the habits of white privilege; their characters and modes of interaction with the world just will be constituted in ways that are morally damaging.”

So how can a white person really live a moral and authentic life in the circumstances of South Africa at the beginning of the 21st Century? Certainly not by attempting to minimise or deny the evil of apartheid. Certainly not by attempting to escape the dilemma by claiming not to have benefited from the system. Rice is rather more pessimistic than I would be about this. She states flatly “I do not think that it is possible for most well-intentioned white South Africans who grew up in the Apartheid years to fulfill their moral duties and attain a great degree of moral virtue.”

Her prescription to deal with this moral issue is that whites should adopt a demeanour of humility and silence. I agree with the humility part, but not necessarily with the silence part.

In the face of the great moral evil that apartheid represents, humility on the part of whites is most definitely appropriate. We benefited greatly from a great evil, there is no doubt about that; even though many white individuals might have struggled through the apartheid years, their struggles were not of the same order, either physically or morally, as the struggles of blacks.

From that position of humility, of appropriate contrition for apartheid, we should express our solidarity with all South Africans in the struggle for a just, more equitable society, to listen to others with openness in order to understand what they would expect from us in the struggle, to accept black leadership and initiative in these matter.

Neither condemnation nor retreat is likely to be useful. A humble engagement might help ourselves and the country more. Failure to do this, failure to commit to the struggle to overcome the painful legacy of apartheid, will in a very real sense mean forfeiting our right to stay here.