A unique and brave musician

“This is the uniqueness of this man: he jolts with the unexpected and the new. He has something to say and he will use every resource to interpret his messages.” – Dr Edmund Pollock, Ph.D., Clinical Psychologist. (From the liner notes to the album The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady , 1963)

I wonder how many other jazz musicians would have invited their therapists to write liner notes for their albums? Charles Mingus was a unique and brave jazz musician, and the tribute to his qualities by his therapist is both fitting and insightful.

Few jazz musicians could have achieved what Mingus did in terms of taking jazz into a totally new space while maintaining strong, clear roots in the history (and stories) of both the music itself and the people who played it.

Two Charles Mingus albums reach their 50th anniversary this year, both recorded by Teo Macero at the 30th Street Studios of Columbia Records, the same studios which produced Miles Davis’s classic Kind of Blue and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out in the same year. Macero was clearly a busy man! And a very perceptive, sensitive one also, to have recognised and promoted such diverse talents, each of whom could make significant contributions to the richness of jazz, the power of its sound, and its huge emotional content and appeal.

In this regard the two Mingus albums stand as significant and beautiful manifestations: they are rooted in the history and story, yet are individual responses to that history and story, as Dr Pollock wrote, “Mr Mingus has never given up. From every experience such as a conviction for assault or an an inmate of a Bellevue (a New York psychiatric institution) locked ward, Mr Mingus has learned something and has stated it will not happen again to him.”

Listening to Mingus is to experience a person with an intense, almost terrifying, self-awareness and a furious determination to share, through his music, the pain, the anger, the joy and elation of this condition we call being human.

To quote Dr Pollock again, this time writing of the three tracks of side B of the original vinyl LP release of Black Saint , though the words could equally be applied to almost any music Mingus wrote or played: “…repeating and integrating harmony and disharmony, peace and disquiet, and love and hate… one is left with a feeling of hope and even a promise of future joy.”

Mingus was a restless searcher for media, styles, forms of music that would be adequate to convey his urgent emotions about and understanding of life. So he listened with “big ears” to the jazz “old-timers” and the new players bringing their own insights and styles to the music, to the old classical composers and the avant garde , always searching for sounds that would express himself, help him to say what he felt he had to say.

As Dr Pollock wrote, with considerable understatement: “Inarticulate in words, he is gifted in musical expression which he constantly uses to articulate what he perceives, knows and feels.”

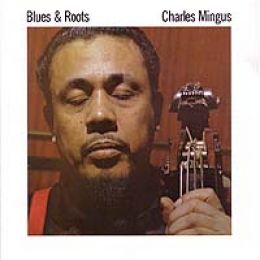

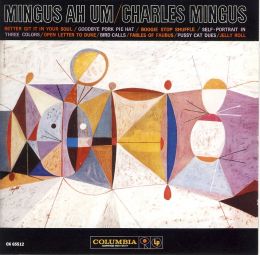

Mingus Ah Um

The first of the two 1959 albums is often regarded as Mingus’s greatest: Mingus Ah Um.

The first of the two 1959 albums is often regarded as Mingus’s greatest: Mingus Ah Um.

The personnel on the album is made up of great musicians, all individualists with their own styles and personalities, who come together brilliantly to blow their hearts out for Mingus. On tenor sax Booker Ervin makes a weighty and soulful contribution. John Handy plays alto, clarinet and tenor on various tracks, the clarinet most notably on “Pussy Cat Blues” which he said was the only time he had played clarinet on a recording. The third tenor seat is held down by Shafi Hafdi, who doubles on alto on some of the tracks. Two trombones complete the horn line-up: Jimmy Knepper and Willie Dennis. The rhythm section consists of, besides the leader, Horace Parlan on piano and long-serving Mingus drummer Dannie Richmond.

Each of these players is noteworthy in their own rights and play significant roles both as soloists and in ensemble work on the album. Besides Mingus, only Parlan, Richmond and Ervin play on all the tracks, the other tracks having different combinations.

Track 1: Better Git It in Your Soul

This album opens with the bluesy, gospelly “Better Git It in Your Soul” which is suffused with the sounds and rhythms that Mingus grew up with in the Holiness Church he attended with his step mother in Watts – it is a foot-stomping, shouting and moaning declaration of all the “harmony and disharmony, peace and disquiet, and love and hate” that Dr Pollock wrote about.

The hand-clapping and shouts (Halleluia! Oh Yes!) add to the “Holiness” feel of the song, which never lets up in emotional intensity throughout its more than seven minutes duration. It’s a stunning and engaging performance.

Track 2: Goodbye Pork Pie Hat

One of Mingus’s best-known compositions follows, his soulful, keening tribute to great tenor sax player Lester ‘Prez’ Young, who had died in March 1959, just two months before this recording date. the title was a reference to Young’s favourite headgear.

The song is a 12 bar blues and, unlike most others of Mingus’s tunes, has been covered by many musicians, including Joni Mitchell who wrote lyrics for it and included it on her Mingus album released in 1980.

Track 3: Boogie Stop Shuffle

Next up is “Boogie Stop Shuffle”, a combination of boogie and shuffle rhythms with stop time. Stop time is defined in Jazz: The Essential Companion (Carr, Fairweather and Priestley, 1988) as “a lengthy series of breaks, so that the rhythm section marks only the start of every bar (or every other bar) for a chorus or more, remaining silent between each of the stop-chords.” On the face of it boogie and shuffle rhythms would seem to be incompatible. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (Kernfeld, 1996) defines boogie as a “percussive style of piano blues” and shuffle as being a “smooth” rhythm “played legato and at a relaxed tempo.” In the hands of Mingus’s group, it makes for exciting and unusual listening, especially with its four themes and alternating backing behind the soloists.

Track 4: Self-Portrait in Three Colours

The next tune, “Self-Portrait in Three Colours”, was originally written for the John Cassavetes movie Shadows, but for budgetary reasons was not used in the film. This is a relatively unusual piece for Mingus in that it is composed throughout, with no solos or improvisations. It starts in a quiet, beautiful way, just piano and bass, but then the horns come in with some clever voicings which give the impression of collective improvisation.

Tracks 5 and 6

The next track is a rollicking tribute to Duke Ellington called “Open Letter to Duke” and the following one is an exciting tribute to Charlie Parker called “Bird Calls.” Of this latter song Mingus wrote, “It wasn’t supposed to sound like Charlie Parker. It was supposed to sound like birds – the first part.”

Track 7: Fables of Faubus

“Fables of Faubus” comes next on the programme. This is a searing, angry meditation on segregation and injustice, occasioned by the attempts of Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus who attempted to prevent the integration of schooling in the state in the 1950s by sending the Arkansas National Guard to block the entry of African American students into Little Rock Central High School in defiance of a Supreme Court ruling. This piece was one Mingus returned to again and again in his career, giving voice to his strong feelings about justice and freedom.

Tracks 8 and 9

The next track, “Pussy Cat Dues” is a stunningly lovely down-tempo blues with some brilliant solo work by Handy, Knepper and Handy. Simply exquisite playing and brilliant arranging. Knepper especially stands out on this number, as he does on the next, called “Jelly Roll”.

Tracks 10, 11 and 12

The last three tracks on the 1998 re-issue are bonus tracks not found on the original LP. Indeed many of the tracks on the re-issue are released at full length for the first time as they were edited into shorter versions for the LP. The tracks are “Pedal Point Blues” which features Mingus joining Parlan on another piano, “GG Train” and the only non-Mingus composition on the album, “Girl of My Dreams.”

The rewards of open ears

This album is a great example of authentic, real music. It is definitely not “easy listening” but will reward anyone willing to really listen with some moments of transcendent beauty, deeply spiritual experience and true feeling.