The making of music history

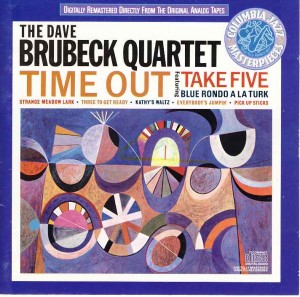

What happened when producer Teo Macero, who had just months before had Miles Davis and his musicians in the Columbia 30th Street Studio to record, brought Dave Brubeck and his quartet into the same studio, was to make more jazz history – the album Time Out with the hit track “Take Five”.

What happened when producer Teo Macero, who had just months before had Miles Davis and his musicians in the Columbia 30th Street Studio to record, brought Dave Brubeck and his quartet into the same studio, was to make more jazz history – the album Time Out with the hit track “Take Five”.

So in three days of recording in the summer of 1959 the Dave Brubeck Quartet, already popular even outside of jazz circles, made an album which would send their popularity into orbit, even gaining them recognition on the Billboard Charts in 1961 in the categories “pop album” where the album reached second spot, “adult contemporary”, where “Take Five” ranked 5th, and “pop singles” where the same number reached the 25th spot. Not bad for a jazz outfit playing some fairly challenging music in time signatures very far from the standard four-in-a-bar pop tunes.

The album is probably the most famous of all jazz albums, especially seeing that it is known by people who are not jazz fans per se .

Time Out is sometimes derided by jazz purists as something like “jazz lite” in spite of the rather awesome intellectual gifts that spawned it.

Brubeck on Time

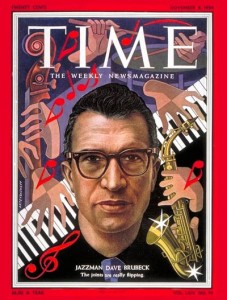

Dave Brubeck had already appeared on the cover of Time magazine (the second jazz artist to do so -the first was Louis Armstrong) by the time Time Out was recorded. This was in November 1954 when the magazine described him as playing “some of the strangest and loveliest music ever played since jazz was born.” And that was five years before Time Out . (I can’t help thinking about the different meanings of “Time” in the magazine and album titles).

Dave Brubeck had already appeared on the cover of Time magazine (the second jazz artist to do so -the first was Louis Armstrong) by the time Time Out was recorded. This was in November 1954 when the magazine described him as playing “some of the strangest and loveliest music ever played since jazz was born.” And that was five years before Time Out . (I can’t help thinking about the different meanings of “Time” in the magazine and album titles).

Brubeck himself had studied with Darius Milhaud who advised him to keep on with jazz improvisation. But the modern “classical” training shows through in the way Brubeck handles both harmony and rhythm. Clearly the time spent with Milhaud was very instructive for Brubeck.

Track 1: Blue Rondo a la Turk

The first track, “Blue Rondo a la Turk” is based partly on the Rondo in Mozart’s Piano Sonata No 11 and the Turkish folk rhythms Brubeck and Company heard on the US Foreign Department sponsored tour the group undertook in the 50s. This tour, in the view of some, was a cold war ploy by the US government, as can be seen from this blog comment (I have unfortunately lost the reference so don’t know where this comes from): “The story behind Time Out placed it squarely as a product of the cold war. Dave Brubeck was sponsored by the US government to tour the periphery of the Soviet Union to show how rich American culture was. This tour took the band to such places as Turkey where the indigenous music and time signatures inspired the album. Hurrah for cultural imperialism.”

I guess that point of view is at least debatable.

Track 2: Strange Meadow Lark

Brubeck can sound very esoteric one moment and the next be downright earthy. This makes for some very interesting listening, and not always that “easy listening.” Listening to how the piano part develops in the second “Strange Meadow Lark” from the almost cocktail lounge style rather long introduction to the way drummer Joe Morello comes in quietly with brushes to bring in a solo from Paul Desmond which is typically lyrical but swinging. Followed by some Brubeck soloing which sounds almost Monkish with very rapid time and key changes going seemingly all over the place. A piece of rare beauty which has hidden depths, like a shallow pool of clear water which suddenly gets very deep and crystalline cold.

Track 3: Take Five

The third track on the album is, of course, that ubiquitous number “Take Five.” This number, written by Desmond as the vehicle for a Joe Morello solo, has become a standard, and has been played almost to death (I even heard a South African band which managed to play the whole song in good old common time, i.e. four beats to the bar, completely ignoring the original time signature which made the song so irresistible in the first place!).

“Take Five” is so strongly associated with Dave Brubeck that to a great number of people it is a surprise to learn that Desmond actually wrote it. The number itself is five minutes of sheer jazz joy, and the solo by Morello which was its original purpose, is stunning in its build up and complexity. Morellohas been described as the most technical of jazz drummers and in this piece he shows exactly why. It is a tour de force of outstanding drumming which holds the listener’s attention from start to finish.

The Side Two tracks

On the original vinyl LP “Take Five” rounded off Side 1. Side two opened with another interesting Brubeck number, “Three to get Ready” which starts, as the name implies, in a rollicking three four or waltz time, then quickly gets into a pattern of three four alternating after two bars with two bars of common time and the pattern repeats throughout the song. This presents more of a challenge to listeners than it seems to have done to the musicians who seem to be having a ball all through.

The song “Kathy’s Waltz”, named for Brubeck’s daughter, “Everybody’s Jumpin'” and “Pick up Sticks”, another Morello vehicle, follow.

The amazing Paul Desmond’s unique sound and contribution

The quartet was made up of musicians who were each of them outstanding in their own ways, but perhaps the most outstanding was Desmond, who’s sound really gave the quartet its unique timbre, its signature feel.

Many people have not appreciated the Desmond sound or his music, putting it into a category, boxing it in, and then condemning it for qualities applicable to the box or category, but not necessarily to the man and his music.

One who appreciates Desmond is avant-garde readman Anthony Braxton, who said of Desmond: “I have never stopped loving this man’s music. The first thing I recall that struck me about it was his sound. The sound grabbed me.”

Braxton went on to say, in interviews with Graham Lock (Forces in Motion , Quartet Books, 1988): “I think Paul Desmond’s music is widely misunderstood on many levels. He was fashionable for the wrongs reasons and he was hated for the wrong reasons.”

Desmond himself once made the comment, “I have won several prizes as the world’s slowest alto player, as well as a special award in 1961 for quietness.” So Braxton’s next comment is especially rich: “He was far ahead of what you heard: what you heard had been edited completely, only the essence remained. Desmond understood how to get to the point quicker than most players ever learn. This is a lightening-fast improviser, who understood sound logic and how to prepare the event.”

The clarity of both his sound and his thinking certainly shine through on all the tracks on this masterful album, and provide some of its highest moments.

And maybe what has attracted so many to this album, making it one of the most successful jazz albums ever made, is captured in Braxton’s comment: “You can say what you like, but masters can touch your heart and change your life. In the case of Desmond, I know that’s true.” (Emphasis in the original)

So in the somewhat unlikely event that you have not heard this album, may I respectfully suggest you go out and get a copy. You will not be disappointed.