Back in those unenlightened, un-wired days of 1967, I and my then girl-friend used to attend art classes at the old Cape Town Art Centre on Greenpoint Common. And every Sunday evening there was a jam session there which we also often attended.

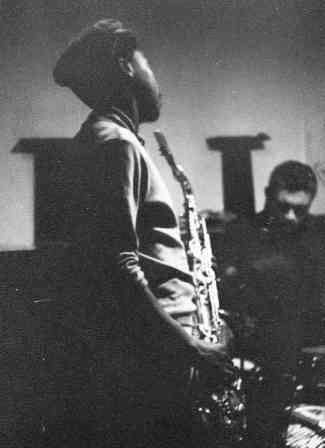

One of the players at these sessions was one Winston Mankunku Ngozi. He was dynamite in a cloth cap indeed.

Those sessions, usually with Midge Pike on bass and Monty Weber on drums, were incredibly good. There was a pianist also but I can’t remember who he was.

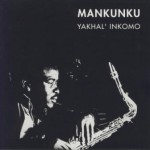

Of course Mankunku was the one who released into the South African soul that instantly-recognisable anthem which electrified the townships much better than Escom ever could, “Yakhal’ inKomo”! And he is best known for that wonderful song.

The album on which it appeared, also called Yakhal’ inKomo, has been re-released many times and is still one of the top selling South African jazz albums of all time. One only has to listen to the album to understand why – those sounds are just dripping in soul and emotion, gripping and beautiful.

Having heard Mankunku play the song live, however, just makes the recording sound rather flat. No recording could ever capture the soul of the man in full-throated roar. It was simply awe-inspiring to hear.

Which is not to say the recording doesn’t merit serious listening – of course it does. It is an amazing album with some pretty amazing musicians on it.

The story of the album and its title is sometimes disputed, but in essence I think the reason it found such resonance in the townships (and, of course, elsewhere) is that it touched on a particularly raw edge at the time, the raw edge of the pain of apartheid, the pain of life in the townships, in a way that had never before (and not since either) been touched.

Mankunku at the Cape Town Art Centre. Midge Pike in the background and Monty Weber partially obscured

As soon as those opening notes from Agrippa Magwaza’s bass come from the speakers one knows one is in the presence of a very special musical experience. The soulful funky groove laid down by Magwaza and pianist Lionel Pillay in the title track makes a fine foundation for the entrance of Mankunku’s declamatory horn. It is a moment of jazz magic, one that is unique among South African jazz albums.

By the time Mankunku died in October 2009 he was a true legend of South African music, a tenorman without peer in the land.

At a time when many of his contemporaries were leaving South Africa to escape the strictures of apartheid Mankunku refused to go. He stayed on in the country in spite of all the hassles of trying to stay alive in a society that was not just oblivious to his greatness, but actually in many ways sought to deny it.

As a result Mankunku had to suffer many indignities and try to fend off the deleterious effects of them on his physical health. In one famous incident, to circumvent the law against mixed bands, he played his tenor behind a curtain while a white musician mimed his moves in front of the curtain. I don’t think many listeners were fooled, but it kept the authorities at bay.

To survive such things takes enormous ego strength and self-belief. And yet Mankunku was almost self-effacing, not pushing himself into the limelight at all. Hence for many he was more of an absence than a presence, and yet when one experienced him in the context of a group playing he was powerful and energetic.

Mankunku was born in 1943 in Retreat on the Cape peninsula outside Cape Town. He was born into a musical family and as a teenager he began to tenor and alto saxes. John Coltrane and Horace Silver were major influences, as were famed Cape Town reedman “Cup and Saucers” Kanuka and bassist Midge Pike.

It was in Midge Pike’s band that Mankunku began his career as a professional musician. It was a career that would include working with many of the greatest names in South African jazz: Dudu Pukwana, Chris McGregor, Barney Rachabane and Victor Ntoni.

The last time I heard Mankunku live was at the Carling Circle of Jazz gig on Greenmarket Square, Cape Town. On that occasion Mankunku gigged with the Victor Ntoni big band and guest artist Chris McGregor. It was a beautiful moment.

On that occasion old friends played with him: Barney Rachabane, Duke Ngcukana, Ezra Ngcukana and Johnny Mekoa, among others. There was also a strong contingent of the younger generation of players like Rashid Lanie, Vusi Khumalo and Bakhiti Khumalo.

However great his other accomplishments, however, the song that remained linked with Mankunku in the minds of jazz lovers in South Africa was “Yakhal’ inKomo.” It was such an important song – in much the same way as Abdullah Ibrahim’s “Mannenberg” would become – in social terms too.

As Mongane Serote wrote about Mankunku: “He just went deep, right down to the floor of despair, and reached the rim of fear and hatred. He just spread and spread out and out in meditation, with his horn, Mankunku, Ngozi, that guy from the shores of South Africa, and he said: ‘That was it.’ For that is what he was doing with his horn, Yakhal’ inKomo…” (Quoted in Michael Titlestad’s Making the Changes, Unisa Press, 2004).

Partial discography

At the time I was listening to Mankunku in Cape Town his seminal and most famous album, Yakhal’ inKomo, had not yet been released and he was not the famous tenorman he became. This album was released in 1968, and has since sold well over 50000 copies – an astounding achievement for a South African jazz which album. The title track is one of those songs that is almost instantly recognised by music fans – they only have to hear the first bar or two and they are already excited! The personnel on this album included, as mentioned, Agrippa Magwaza on bass, Lionel Pillay on piano, with Early Mabuza laying down the beat at the drumkit. The story behind this album seems to depend on who tells it. My own friend Ernest Mothle shared with me his version. Whatever the truth, it remains a superb, exciting, moving album from a musician who was only 24 when he made this recording.

At the time I was listening to Mankunku in Cape Town his seminal and most famous album, Yakhal’ inKomo, had not yet been released and he was not the famous tenorman he became. This album was released in 1968, and has since sold well over 50000 copies – an astounding achievement for a South African jazz which album. The title track is one of those songs that is almost instantly recognised by music fans – they only have to hear the first bar or two and they are already excited! The personnel on this album included, as mentioned, Agrippa Magwaza on bass, Lionel Pillay on piano, with Early Mabuza laying down the beat at the drumkit. The story behind this album seems to depend on who tells it. My own friend Ernest Mothle shared with me his version. Whatever the truth, it remains a superb, exciting, moving album from a musician who was only 24 when he made this recording.

The next album featuring Mankunku is a strange one, though also beautiful. It is called The Lion and the Bull and pairs Mankunku with fellow-tenorman Mike Makhalelemele in front of, of all things, a white pop group called “Rabbit” which comprised wizard guitarist Trevor Rabin (who later joined Rick Wakeman and Jon Anderson in “Yes“), bass guitarist Ronnie Robot and drummer Neil Cloud. This album (plus a large number of other South African classic albums) can be downloaded free at Electricjive. As journalist and later record producer Patric van Blerk wrote about this album at the time: “This album brings the magnificent Mankunku together with another very special person – a new and very bright star – Mike Makhalemele. Mike as the Lion could not be more gentle – Winston as the Bull is strong yet alone.The Bull and the Lion will make you feel sexy – and your wash will be whiter.”

The next album featuring Mankunku is a strange one, though also beautiful. It is called The Lion and the Bull and pairs Mankunku with fellow-tenorman Mike Makhalelemele in front of, of all things, a white pop group called “Rabbit” which comprised wizard guitarist Trevor Rabin (who later joined Rick Wakeman and Jon Anderson in “Yes“), bass guitarist Ronnie Robot and drummer Neil Cloud. This album (plus a large number of other South African classic albums) can be downloaded free at Electricjive. As journalist and later record producer Patric van Blerk wrote about this album at the time: “This album brings the magnificent Mankunku together with another very special person – a new and very bright star – Mike Makhalemele. Mike as the Lion could not be more gentle – Winston as the Bull is strong yet alone.The Bull and the Lion will make you feel sexy – and your wash will be whiter.”

In 1986 Mankunku was involved in the recording of yet another classic of South African jazz, Jika, recorded in both Cape Town and London, which featured pianist/arranger Mike Perry and some other great South African musicians living in the United Kingdom like guitarist Lucky Ranku, pianist Bheki Mseleku, trumpetter Claude Deppa and percussionist Russell Herman. As Perry notes, “Jika was composed and recorded during the period here known as ‘the bad years’, ie. when the system of racial oppression called apartheid was at its height under P.W . Botha ‘s ‘Imperial Presidency'”. The word “Jika” mean to turn around, to change. Clearly what was on the minds of those who played the music and produced the album. This album is available for download (though not free!) at Rhythm Music Store.

In 1986 Mankunku was involved in the recording of yet another classic of South African jazz, Jika, recorded in both Cape Town and London, which featured pianist/arranger Mike Perry and some other great South African musicians living in the United Kingdom like guitarist Lucky Ranku, pianist Bheki Mseleku, trumpetter Claude Deppa and percussionist Russell Herman. As Perry notes, “Jika was composed and recorded during the period here known as ‘the bad years’, ie. when the system of racial oppression called apartheid was at its height under P.W . Botha ‘s ‘Imperial Presidency'”. The word “Jika” mean to turn around, to change. Clearly what was on the minds of those who played the music and produced the album. This album is available for download (though not free!) at Rhythm Music Store.

In 1996 Mankunku recorded another album in collaboration with Mike Perry. This was a much more laid-back sort of album, on which bassist Spencer Mbadu particularly shone. The album, called Dudula, meaning “Forward”, is notable especially for the tracks “Khawuleza (Hurry Up)” which features a great solo by Mbadu, and the great song “Shirley” on which Mankunku really shines. This album was recorded in Cape Town. Other tracks on this album are “Amanzi Obomi” (Water of Life); the mbaqanga “Masihambe” (Let’s Go); and “Green and Gold”. Other musicians on this album are Richard Pickett, Errol Dyers, Charles Lazar, Buddy Wells, Marcus Wyatt, Graham Beyer, and the Merton Barrow String Quintet.

In 1996 Mankunku recorded another album in collaboration with Mike Perry. This was a much more laid-back sort of album, on which bassist Spencer Mbadu particularly shone. The album, called Dudula, meaning “Forward”, is notable especially for the tracks “Khawuleza (Hurry Up)” which features a great solo by Mbadu, and the great song “Shirley” on which Mankunku really shines. This album was recorded in Cape Town. Other tracks on this album are “Amanzi Obomi” (Water of Life); the mbaqanga “Masihambe” (Let’s Go); and “Green and Gold”. Other musicians on this album are Richard Pickett, Errol Dyers, Charles Lazar, Buddy Wells, Marcus Wyatt, Graham Beyer, and the Merton Barrow String Quintet.

Mankunku’s next album was the SAMA award-winning Molo Africa of 1999 (released in 1998). Writing  about this album on the All About Jazz site Nils Jacobsen said: “If you listen carefully to what Mankunku has to say, he lingers on melody in the same way Albert Ayler used to, deeply aware and celebrating each note.” A great list of artists appears on this album, including Feya Faku, Tete Mbambisa, Spencer Mbadu, Vince Pavitt, Vusi Khumalo, Graham Beyer, Sylvia Mdunyelwa, Jack Van Poll, Lucien Lewin, Errol Dyers, Basil Moses, Bongiwe Gcabe, George Werner, Octavia Tengeni, Themba Fassie, Boytjie Philiso, Lionel Beukes, Soi-Soi Gqeza, Blackie Thempi, Denver Furness, Sipho Yhintsa, Nopinkie Ngxengane, Mzwandile Ngxengane.

about this album on the All About Jazz site Nils Jacobsen said: “If you listen carefully to what Mankunku has to say, he lingers on melody in the same way Albert Ayler used to, deeply aware and celebrating each note.” A great list of artists appears on this album, including Feya Faku, Tete Mbambisa, Spencer Mbadu, Vince Pavitt, Vusi Khumalo, Graham Beyer, Sylvia Mdunyelwa, Jack Van Poll, Lucien Lewin, Errol Dyers, Basil Moses, Bongiwe Gcabe, George Werner, Octavia Tengeni, Themba Fassie, Boytjie Philiso, Lionel Beukes, Soi-Soi Gqeza, Blackie Thempi, Denver Furness, Sipho Yhintsa, Nopinkie Ngxengane, Mzwandile Ngxengane.

In 2003 Mankunku released his final album (though no-one was to know that) called Abantwana be Afrika (Children of Africa). This album is a “return to roots” type of venture, with a relatively small group backing and Mankunku  himself in quiet mood. The musicians around the master on this album are all of the younger generation of jazz musos in South Africa, but no less interesting for that. Apart from Mankunku on both tenor and soprano saxes the group consists of Prince Lengoasa – flugelhorn, Andile Yenana – piano, Herbie Tsoaeli bass, Lulu Gontsana – drums. All the musicians also share in performing the vocal chores. This is a stunningly beautiful album showcasing Mankunku at his best in terms of warmth of tone and emotional expressiveness. The track listing is “Give Peace a Chance (Een Liedtjie vir Saldanha Bay)”, “Ndizakuxhela Kwamajola”, “Bantwana Be Afrika (Children of Africa)”, “George & I”, Makaya Davashe’s incredibly beautiful “Lakutshon’ Ilanga”, “Dedication (to Daddy Trane & Brother Shorter)” which Mankunku debuted on the Yakhal’ inKomo album, “Inhlupeko”, “Tshawe”, “Ekuseni”, “Thula Mama”. A treat indeed.

himself in quiet mood. The musicians around the master on this album are all of the younger generation of jazz musos in South Africa, but no less interesting for that. Apart from Mankunku on both tenor and soprano saxes the group consists of Prince Lengoasa – flugelhorn, Andile Yenana – piano, Herbie Tsoaeli bass, Lulu Gontsana – drums. All the musicians also share in performing the vocal chores. This is a stunningly beautiful album showcasing Mankunku at his best in terms of warmth of tone and emotional expressiveness. The track listing is “Give Peace a Chance (Een Liedtjie vir Saldanha Bay)”, “Ndizakuxhela Kwamajola”, “Bantwana Be Afrika (Children of Africa)”, “George & I”, Makaya Davashe’s incredibly beautiful “Lakutshon’ Ilanga”, “Dedication (to Daddy Trane & Brother Shorter)” which Mankunku debuted on the Yakhal’ inKomo album, “Inhlupeko”, “Tshawe”, “Ekuseni”, “Thula Mama”. A treat indeed.

© Text and photos copyright Tony McGregor