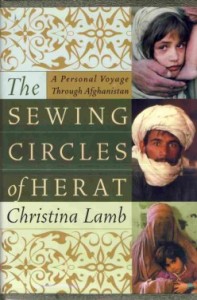

War isn’t beautiful

“War wasn’t beautiful at all. It was the ugliest thing I had ever seen and it made me do the ugliest thing I had ever done. The real story of war wasn’t about the firing and the fighting, some Boy’s Own adventure of goodies and baddies. It wasn’t about sitting around in bars making up songs about the mujaheddin we called ‘The Gucci Muj’ with their designer camouflage and pens made from AK47 bullets. It was about the people, the Naems and Lelas, the sons and daughters, the mothers and fathers.” – from Christina Lamb’s The Sewing Circles of Herat (HarperCollins, 2002).

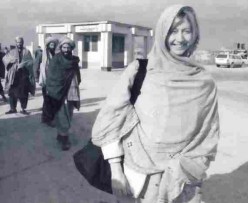

“Dizzy with Kipling and diesel fumes.”

“Dizzy with Kipling and diesel fumes.”

The Sewing Circles of Herat is about the human cost of the “great game” that has been played in and about Afghanistan by the three major powers of imperial Britain, Soviet Russia and the United States, each of them playing the game by the rules of their own particular perceptions of realpolitik , their own interests in the stony and impoverished land made, according to Pashtun legend, from a pile of rocks left over when Allah had finished making the rest of the world.

Lamb’s book, quite different from David Loyn’s Butcher and Bolt , is the story of a foreign correspondent’s personal experiences in the roiling cauldron of violence that has been Afghanistan for the past 30 years, since the December 1979 invasion by the Soviet army, violence that has only increased in intensity since the horror of 9/11.

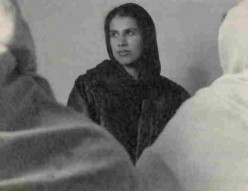

It is also the story of a young woman, Marri, who wrote a series of letters and a diary during the dark days of the Taliban oppression “On my desk is a handful of letters from a woman of about my own age in Kabul. She risked her life to get them to me and this is also her story.”

The two intersecting stories make for a very moving and at times horrifying read, starting from Lamb’s arrival in Afghanistan, “…stumbling out of a battered mini-bus in the Old City of the frontier town of Peshawar, dizzy with Kipling and diesel fumes.”

“If ever there was a country whose fate was determined by geography,” writes Lamb, “it was the land of the Afghans.”

While Afghanistan was never a colony, it has “always been a natural crossroads – the meeting place of the Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and the Far East – and thus frequently the battlefield and graveyard of great powers. Afghans spoke of Marco Polo, Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, and Tamerlane, as well as various Moghul, Sikh and Persian rulers as if they had just passed through.”

Into this complex land Lamb came as a “gawky English girl”, a “graduate of philosophy at university and of adolescence in British suburbia”, to witness at first hand the struggle of the mujaheddin against the Soviet occupiers and then again, 12 years later, the effects of the “war on terror” that followed the 9/11 attacks in New York.

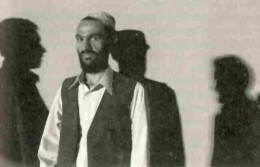

The torturer

One of Lamb’s early encounters after the fall of the Taliban was with 30-year-old Mullah Khalil Ahmed Hassani, a business studies graduate from Peshawar University. He was forced to leave his job as an accountant for a trading company in Quetta to join the Taliban who had arrested Hassani’s 85-year-old grandfather in Kandahar and would only release him if a male member of the family joined up.

Hassani was drafted into the secret police and at first patrolled the streets looking for anyone disobeying the many intricate and often absurd regulations such as: women not allowed to buy from male shopkeepers; any woman showing her ankles to be whipped; a ban on shoes with heels or that make any noise as no stranger should hear a woman’s footsteps; a ban on cosmetics, meaning that any woman with painted nails should have her fingers cut off.

A later assignment for the “Taliban torturer” was to guard some shipping containers full of Hazara women and children. Hazaras had been declared, by the governor of Mazar-i-Sharif, Mullah Manon Niazi, non-Muslim “Kofr” and thus “legitimate” targets for the worst possible treatment.

In the 40 plus degree Centigrade heat the 450 or so prisoners were kept in the containers without water, food, or toilet facilities, in what Hassani called “among the worst of many bad things” he and his men had been forced to do. “I can still hear the noise, the desperate banging on the metal and the muffled cries that gradually grew softer,” Hassani told Lamb.

Marri’s story – a bird singing in the tree

“…I hope this will help you outside understand the feelings of an educated Afghan female who must now live under a burqa.” – Marri’s first letter to Christina Lamb, dated 24 September 2001.

Marri and Christina did not know each other when Marri first wrote to Christina. The process of learning about each other, the discovery of the humanity behind the rhetoric of Afghanistan symbolised by their search for each other, is the focus of this book, which makes it indeed as much Marri’s as Christina’s story.

On 13 November 2001 Marri wrote to Christina: “Kabul is free, can you believe it!” The Northern Alliance had advanced on the city and the Taliban had left, as Marri wrote, “like thieves in the night.”

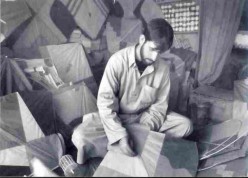

After the Taliban rule ended Marri wrote of the return of simple, everyday things that had been banished by the religious fanaticism: “Our new neighbours have small children and they are laughing – their father has brought them a pink and green paper kite and it is flying high in the sky. How long it is since we heard laughter – now imagine, that was banned too.”

Marri ends this letter: “This is a sweet night.”

In a diary entry in February 2002 Marri wrote, “Soon it will be spring, there will be cherry blossoms, maybe we will hang up our burqas for good and even start to love again.”

During the Eid holiday in 2001 Christina began to search for Marri in the crowded part of Kabul called Microrayon, having only Marri’s letters to guide her. The search lasted two months, two months of meeting and questioning many, many people, following false leads and getting discouraged.

It was only on the day before Christina was due to leave Afghanistan that she got word that her helper Tawfiq Massood had found Marri, not in Microrayon but on the other side of Kabul, where she and her family had fled to escape the noise and the bombs.

“Since the Taliban left I cannot stop smiling,” Marri told Christina. “The snows have come back to the city and today there was a bird singing in the tree. And now you have come.”

Christina pointed out that Marri had taken a huge risk in writing and smuggling the letters out of Afghanistan, and asked why she had done it.

“We thought we were the forgotten people,” Marri said. “…it gave us hope that someone somewhere wanted to know…”

When they parted Marri gave Christina a parcel wrapped in a cloth – when Christina opened it she found it was Marri’s diary.

“We must never forget”

One of the enduring themes of this book is the survival of human values, human activities, in spite of the dreadful effects of the inhumanity of war and religious fanaticism, ideology and economics.

One symbol of that was the Sewing Circles of Herat, which give the book its title. Under the Taliban, literature, especially Western literature, was a forbidden subject, especially for women, who were not allowed education of any sort.

In an alley in Herat was a doorway with the sign: “Golden Needle, Ladies’ Sewing Classes, Mondays, Wednesdays, Saturdays”.

“Three times a week for the previous five years, young women, faces and bodies disguised by their Taliban-enforced uniforms of washed-out blue burqas and flat shoes, would knock at the yellow wrought-iron door. In their handbags, concealed under scissors, cottons, sequins and pieces of material, were notebooks and pens.”

This was the home of Mohammed Nasir Rahiyab, professor of literature at the Herat University, where he gave the women lessons on literary criticism, aesthetics and poetry, including western classics. All subjects forbidden by the Taliban, more especially to women.

Why run this “Sewing Circle”?

The professor explained: “If the authorities had known that we were not only teaching women, but teaching them high levels of literature we would have been killed. But a lot of fighters sacrificed their lives over the years for the freedom of this city. Shouldn’t a person of letters make that sacrifice too?”

The professor added: “A society without literature is a society that is not rich and does not have a strong core. If there wasn’t so much illiteracy and lack of culture in Afghanistan then terrorism would never have found its cradle here.”

Words of amazing optimism in a land in which, in a few years, one-and-a-half million people had been killed, and millions more horribly injured and displaced. And typical of the incredible power of the human spirit to endure and to choose life, if not to flourish, even in the most unconducive conditions.

As Christina’s friend Hamid Gilani put it in the final words of this fascinating and important book, “… we lost so many people. One and a half million. That’s too big a number. Every one of them had their story and we must never forget.”

Copyright Note

The text on this page, unless otherwise indicated, is by Tony McGregor. The illustrations are taken from the book The Sewing Circles of Herat by Christina Lamb (HarperCollins, 2002) and are copyright by the author.

Should you wish to use any of the text feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2012