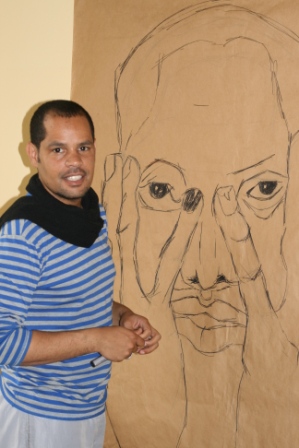

“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

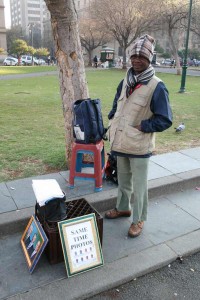

What is the meaning of art in the South Africa of the 21st Century? Wesley Pepper is answering that question by doing art, not theorising about it.

The Johannesburg-based artist was born in Kimberley in the Northern Cape

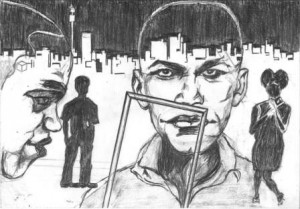

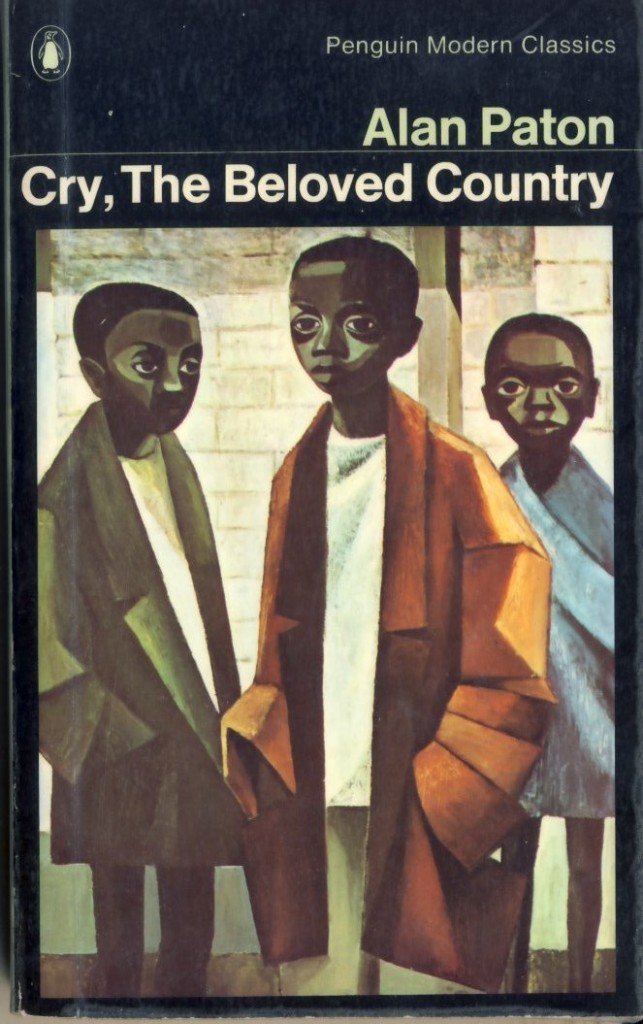

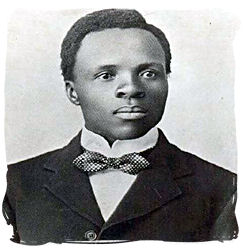

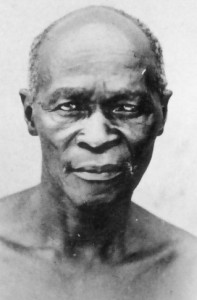

“Dark skin” – a drawing by Wesley Pepper which was included in a collection of poetry by local writers

Province of South Africa in July 1978. He studied art, majoring in oil painting and drawing, at the Free State Technicon in neighbouring Bloemfontein before moving to Port Elizabeth where he studied computer graphics at a Further Education and Training (FET) college, before moving on to Cape Town.

After a short stay back in Kimberley where he was active in an arts-and-crafts collective Pepper moved to Johannesburg in 2002.

“I sold a piece within five hours of arriving here,” he says with characteristic enthusiasm.

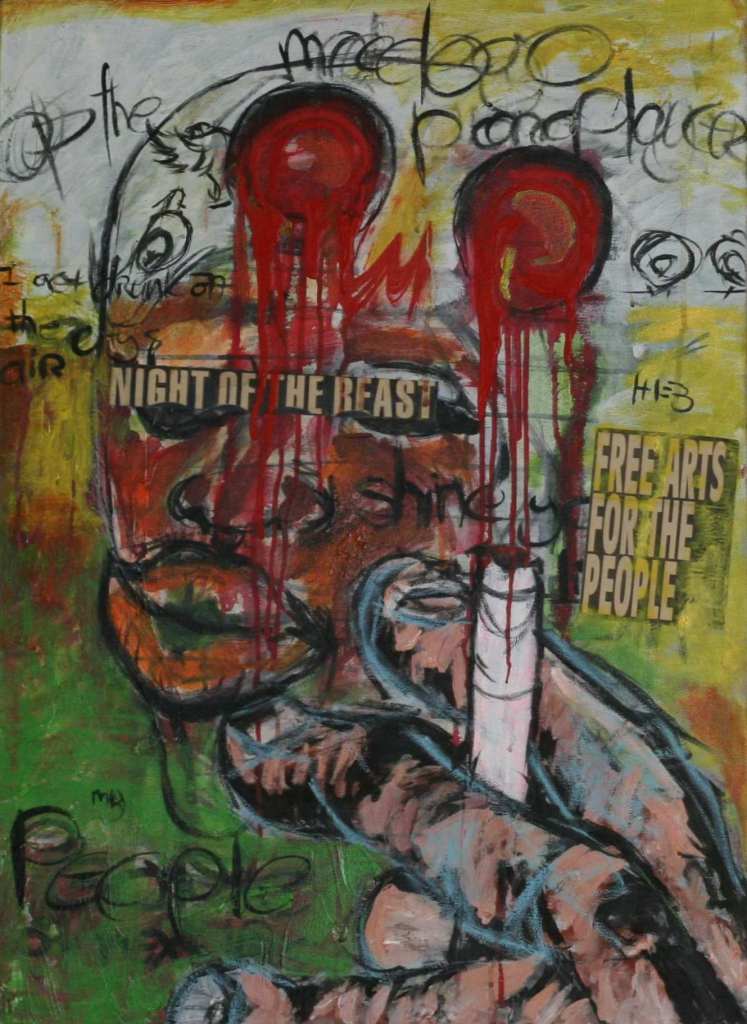

A concern that Pepper expresses is about the commercialisation of art: “People look at the price tag before they look at the work.”

He would like with his art to challenge the conservative world-views of many South African communities with regard to art, the conservatism of blue suits and ties!

The challenge Pepper makes is through his engagement, through postering and workshopping, through involvement with other artists, musicians and writers.

“I call my art ‘open spaces’ coz exactly of that, I involve myself in various spaces and my art is about what I experience,” says Pepper.

Together with local writers Pepper has produced three collections of poetry for which he has provided art works. He has also facilitated creativity workshops and been involved with artists’ collectives.

“I love organising people,” he says.

The collective with which he is currently involved is planning a large exhibition for 2013 – which he says will take art out of the gallery and into the street.

I asked Pepper about his views on what constitutes art, on what an artist is. His

reply: “An artist (according to me) is someone who is conscious about their creativity and has the talent to ‘make art’ and make a living off it.”

“As an artist you are measured by your work and hopefully my work made a statement and that’s what defines me.”

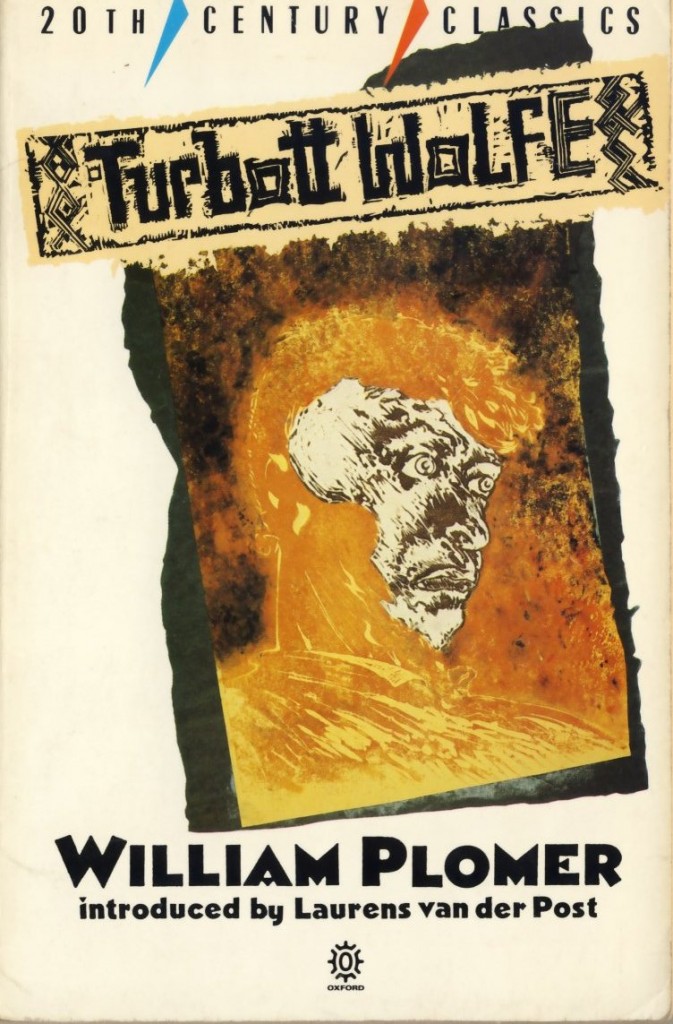

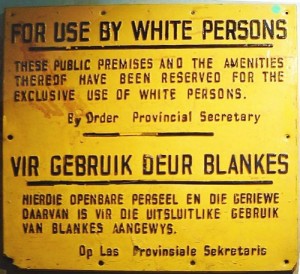

From Apartheid to Zaamheid – a book review

From Apartheid to Zaamheid is a readable and practical book about making a difference, being a positive force for change in South Africa, rather than a perpetual whinger about all that is wrong in the country.

My only complaint really is, why did the book take so long to arrive on my desk? It was published by Aardvark Press in 2004 and yet I only came to see it this week. Well, maybe I’m not as awake as I like to think I am!

The author is Advocate Neville Melville who played a significant role in the transition from the apartheid regime to the non-racial democracy we live in today. He has also been the Banking Ombudsman as well as being appointed by former president Nelson Mandela as the Police Ombudsman.

The book is 130 pages long and presents, in very readable ways, the problems facing South Africa and a number of possible ways that individuals can make contributions to solving these problems – not in grand, sweeping ways, but in small ways that touch people’s lives.

The word “Zaamheid”, Melville explains, he coined from the international symbol for South Africa, namely “ZA”, and the initial letters of the words “alle mense (all people)” to form the “Zaam”, which sounds a lot like the Afrikaans word “saam” which means “together”. The suffix “-heid” means roughly “-ness” as in “apart-ness”.

Melville defines his new word as meaning “everyone working together” and he writes, “The choice of an Afrikaans-sounding word would, in itself, be an act of bridge building.”

That introduces the major theme of the book, which is also its sub-title: “Breaking down walls and building bridges in South African society.”

Some of the chapter titles give an idea of how this theme is explored by Melville: “The crack in the wall”; “The great wall”; “Behind high

In his analysis of the problems facing South Africa Melville makes it clear that the walls, both real and metaphorical, which continue to keep South Africans apart from each other are the source of the ills besetting the country: “The affluent continue to barricade themselves from the rest of the world in security villages with checkpoint controls. The workplace is increasingly becoming a no-go zone for whites, particularly if they are males.”

In the final chapter of the book, “The way ahead”, Melville makes some pertinent points, like “We are, as a country, spending too much of our energies in trading blame and squabbling amongst ourselves. Instead we should be focussing all our efforts into the challenges that face us. Until every last person has a stake in the country’s wealth, none of our individual wealth is secure.”

The book as a whole is a challenge to all South Africans to become bridge builders rather than wall builders.