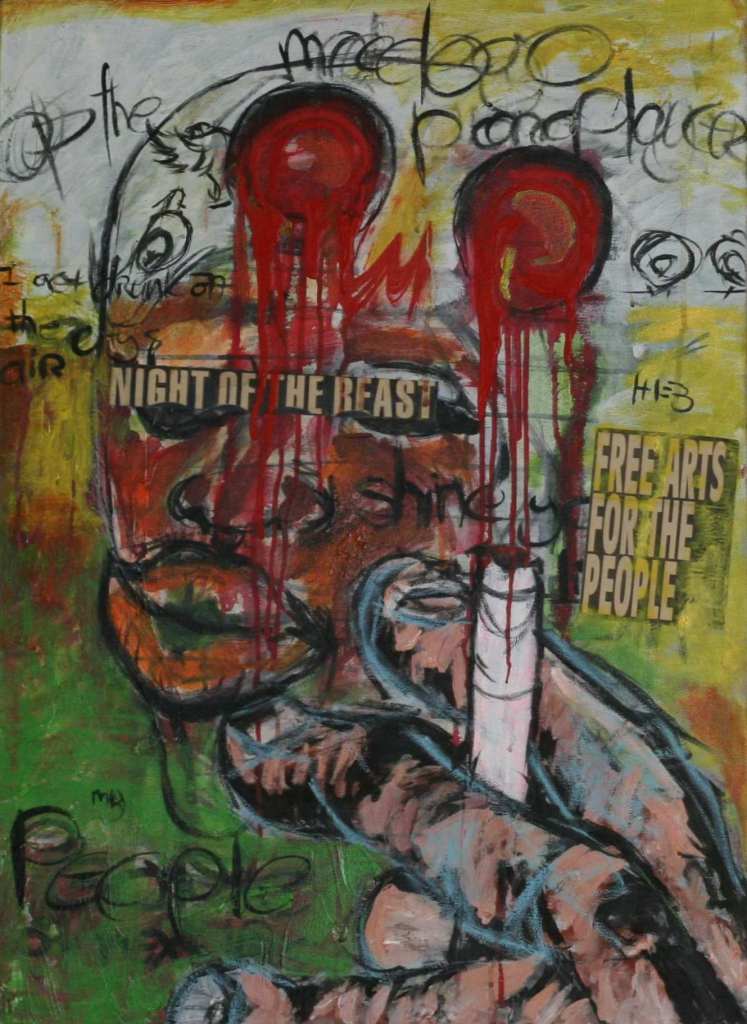

“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

What is the meaning of art in the South Africa of the 21st Century? Wesley Pepper is answering that question by doing art, not theorising about it.

The Johannesburg-based artist was born in Kimberley in the Northern Cape

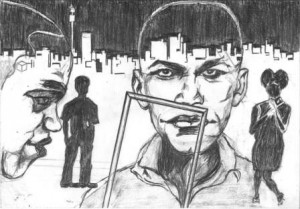

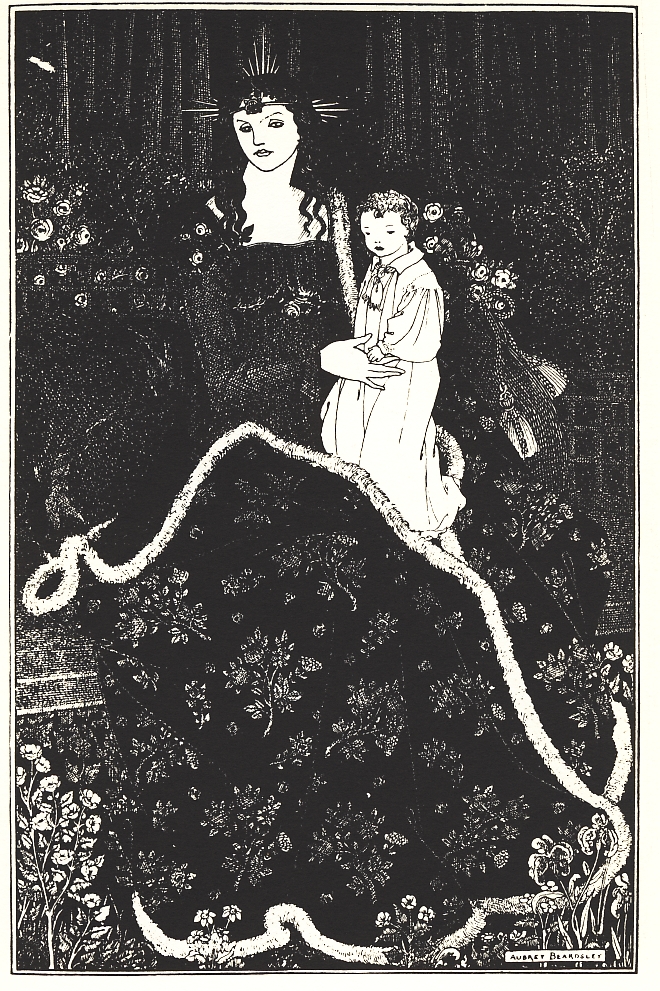

“Dark skin” – a drawing by Wesley Pepper which was included in a collection of poetry by local writers

Province of South Africa in July 1978. He studied art, majoring in oil painting and drawing, at the Free State Technicon in neighbouring Bloemfontein before moving to Port Elizabeth where he studied computer graphics at a Further Education and Training (FET) college, before moving on to Cape Town.

After a short stay back in Kimberley where he was active in an arts-and-crafts collective Pepper moved to Johannesburg in 2002.

“I sold a piece within five hours of arriving here,” he says with characteristic enthusiasm.

A concern that Pepper expresses is about the commercialisation of art: “People look at the price tag before they look at the work.”

He would like with his art to challenge the conservative world-views of many South African communities with regard to art, the conservatism of blue suits and ties!

The challenge Pepper makes is through his engagement, through postering and workshopping, through involvement with other artists, musicians and writers.

“I call my art ‘open spaces’ coz exactly of that, I involve myself in various spaces and my art is about what I experience,” says Pepper.

Together with local writers Pepper has produced three collections of poetry for which he has provided art works. He has also facilitated creativity workshops and been involved with artists’ collectives.

“I love organising people,” he says.

The collective with which he is currently involved is planning a large exhibition for 2013 – which he says will take art out of the gallery and into the street.

I asked Pepper about his views on what constitutes art, on what an artist is. His

reply: “An artist (according to me) is someone who is conscious about their creativity and has the talent to ‘make art’ and make a living off it.”

“As an artist you are measured by your work and hopefully my work made a statement and that’s what defines me.”

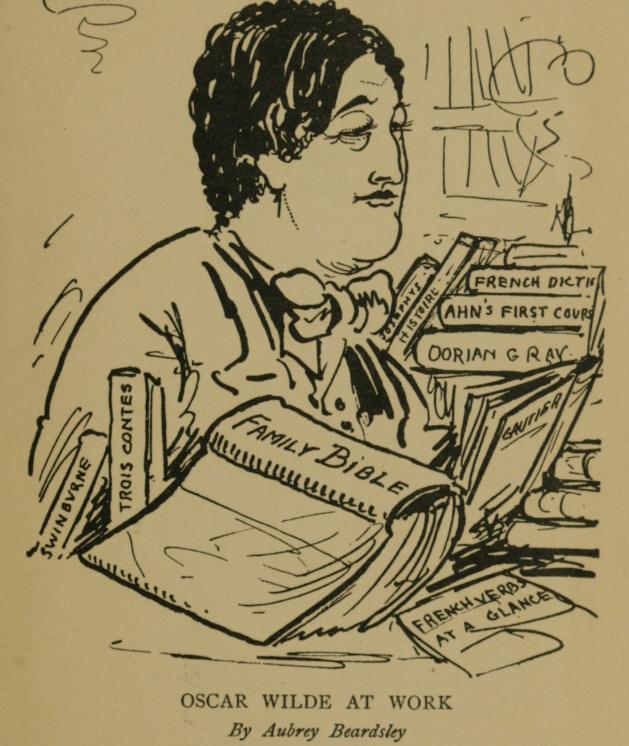

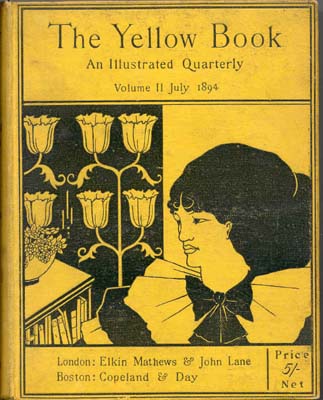

Beardsley was associated with various publications including the

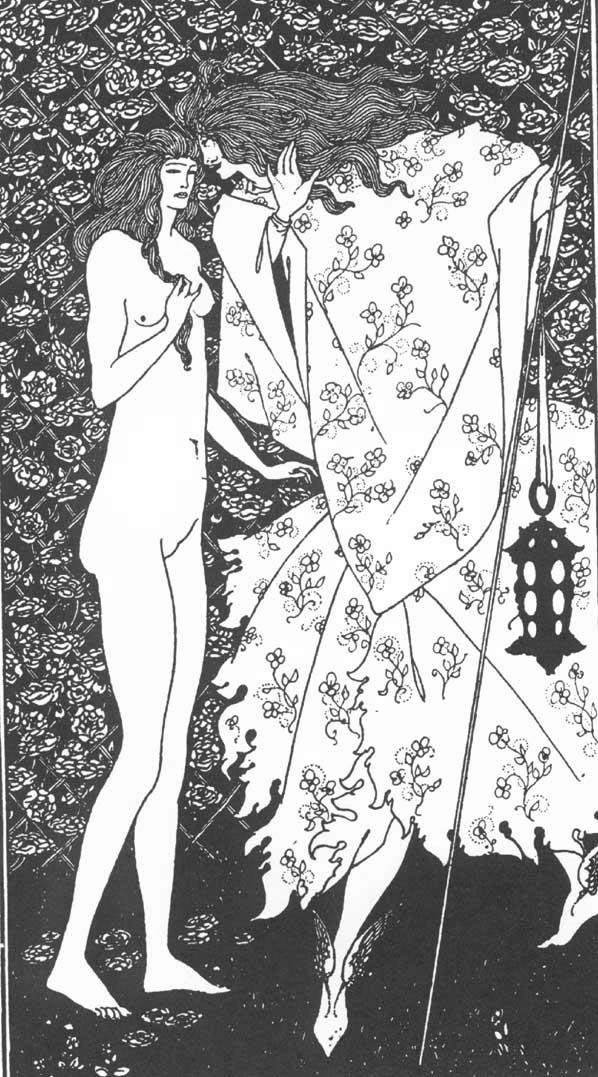

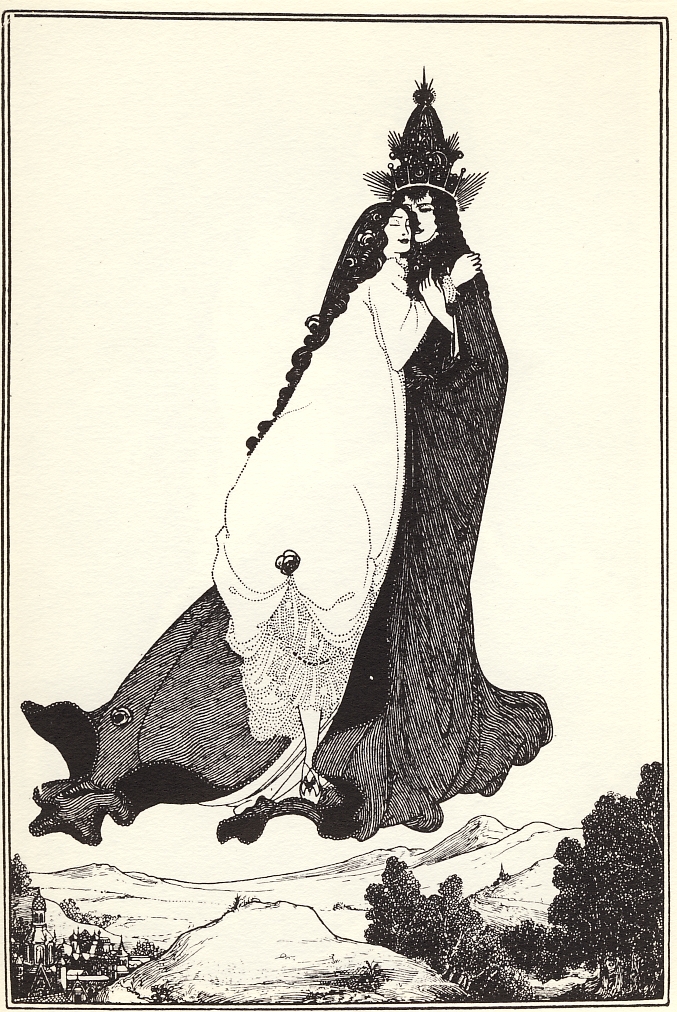

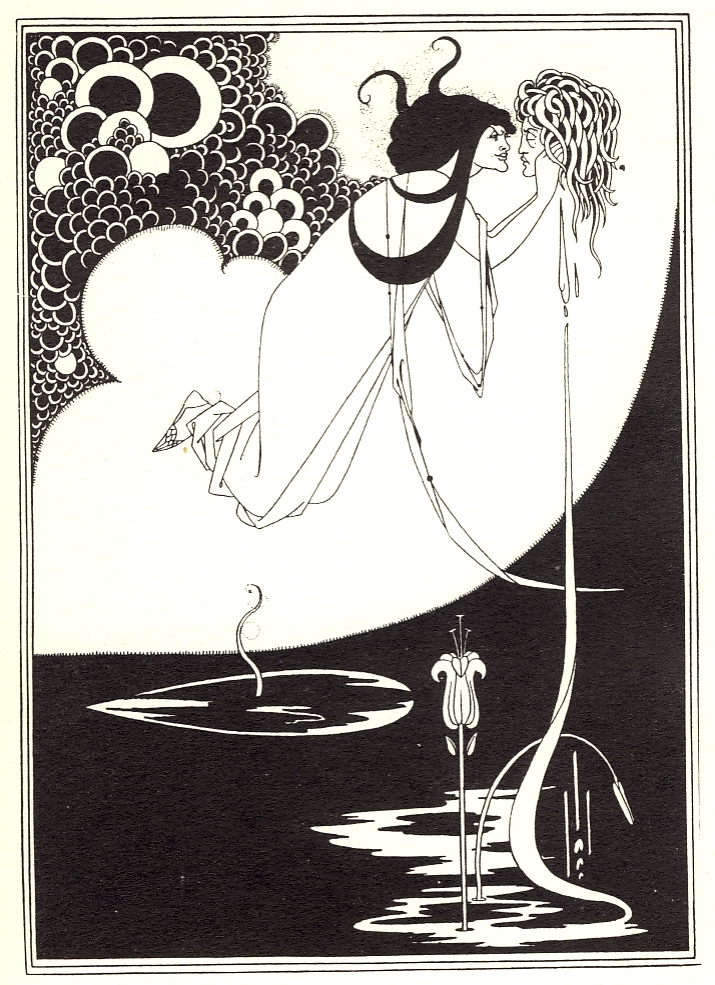

Beardsley was associated with various publications including the  The first of these is the lovely Mysterious Rose Garden, which, according to Stanford, “conveys a sense of Beardsley’s elaborated gospel of sin.” The drawing, “is eminently successful, depending on the contrast between the naked, slender figure of the woman and the voluminously full figure of the ‘Dark Angel’ clad in a swirling loosely skirted robe and bearing his long-tipped staff and glowing lantern.” It is indeed a haunting image of great beauty and not a little disturbing for all that.

The first of these is the lovely Mysterious Rose Garden, which, according to Stanford, “conveys a sense of Beardsley’s elaborated gospel of sin.” The drawing, “is eminently successful, depending on the contrast between the naked, slender figure of the woman and the voluminously full figure of the ‘Dark Angel’ clad in a swirling loosely skirted robe and bearing his long-tipped staff and glowing lantern.” It is indeed a haunting image of great beauty and not a little disturbing for all that.

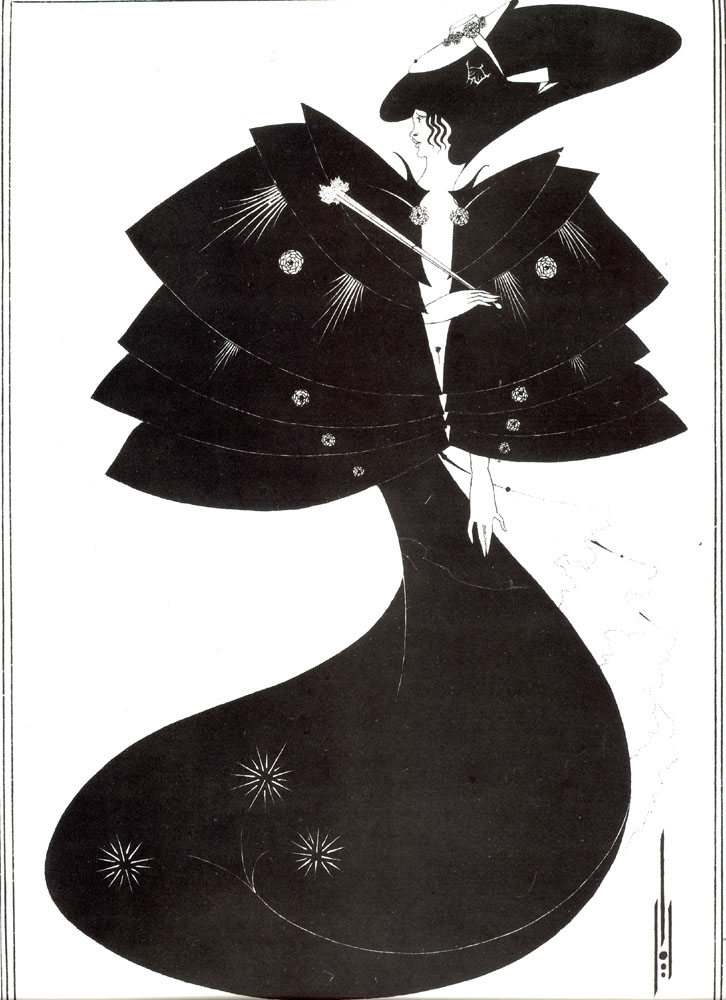

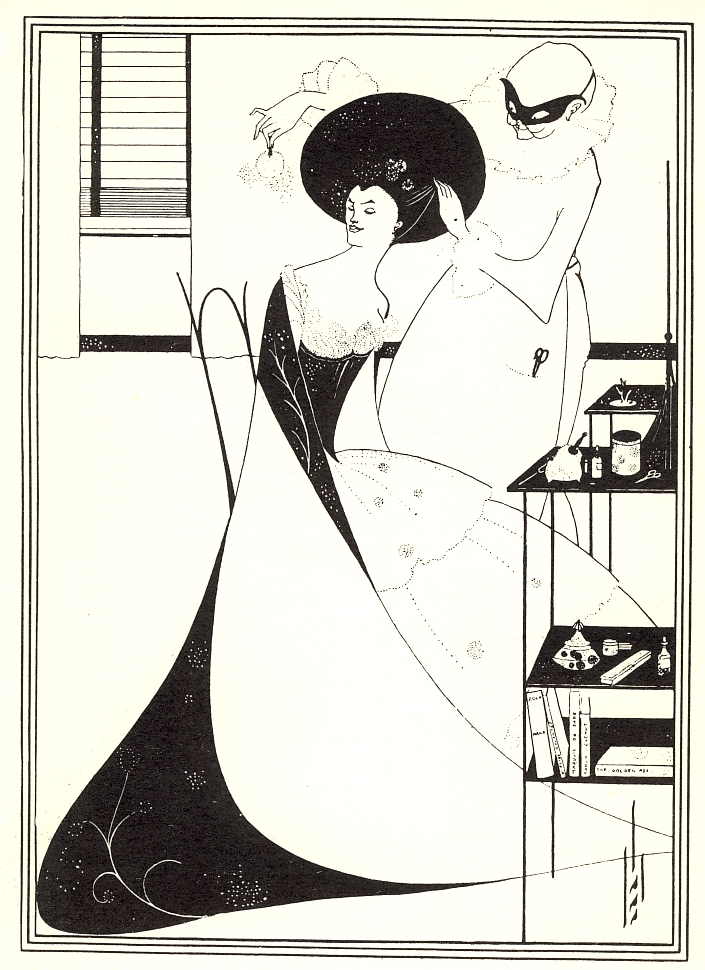

One of Beardsley’s most famous pieces is “The Black Cape”. In this work the influence of Japanese print makers is clear, even to the mark that Beardsley used as his signature. The balance and swirl of this piece is ravishing to the eye, in spite of its being in sober black and white.

One of Beardsley’s most famous pieces is “The Black Cape”. In this work the influence of Japanese print makers is clear, even to the mark that Beardsley used as his signature. The balance and swirl of this piece is ravishing to the eye, in spite of its being in sober black and white.

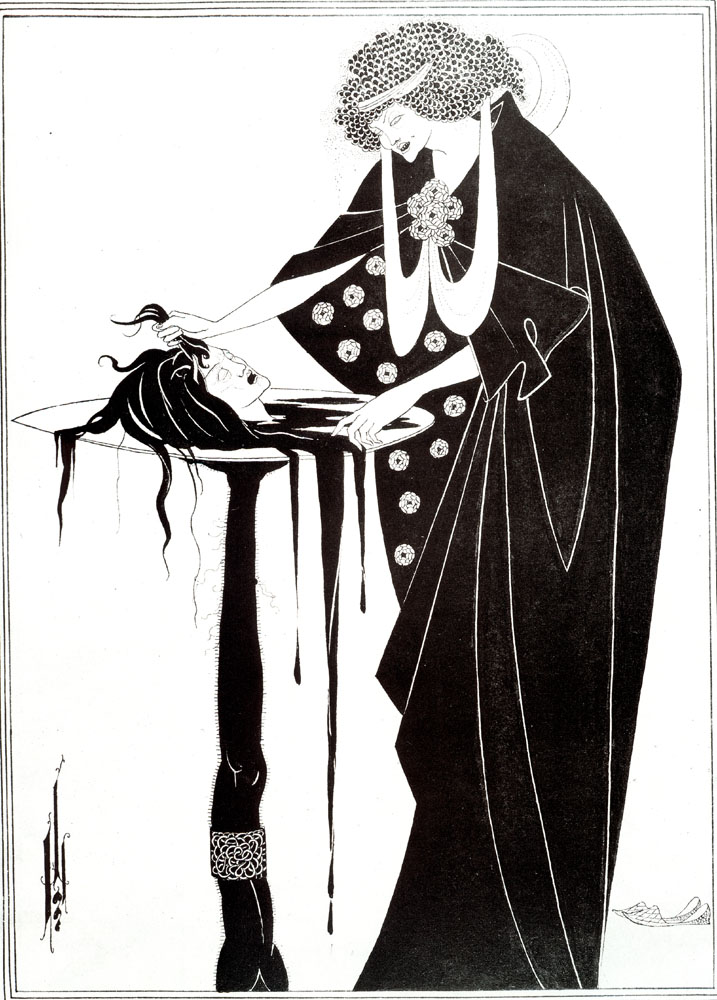

A really horrifying climax in which the illustration, by its starkness captures the horror and strange fascination of it. There is in Salomé’s response the horror of necrophilia, the wild abandon to the lusts of death: “If thou hadst looked at me,” she tells the dead head, “thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.”

A really horrifying climax in which the illustration, by its starkness captures the horror and strange fascination of it. There is in Salomé’s response the horror of necrophilia, the wild abandon to the lusts of death: “If thou hadst looked at me,” she tells the dead head, “thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.”

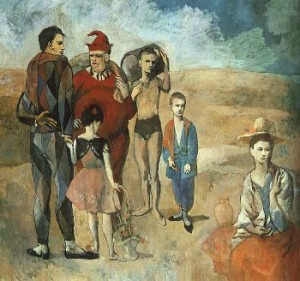

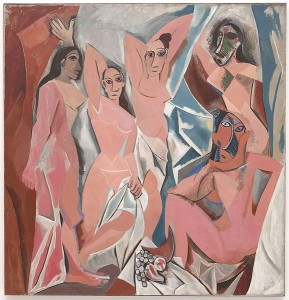

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

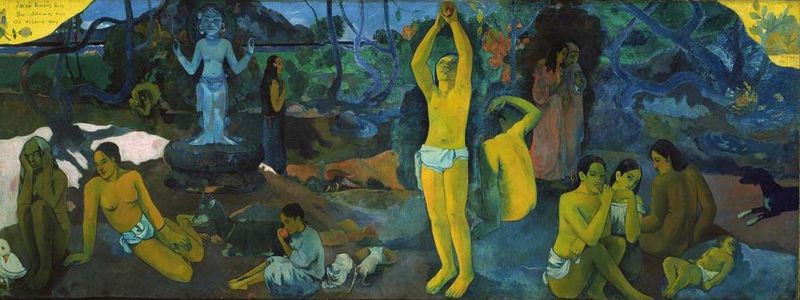

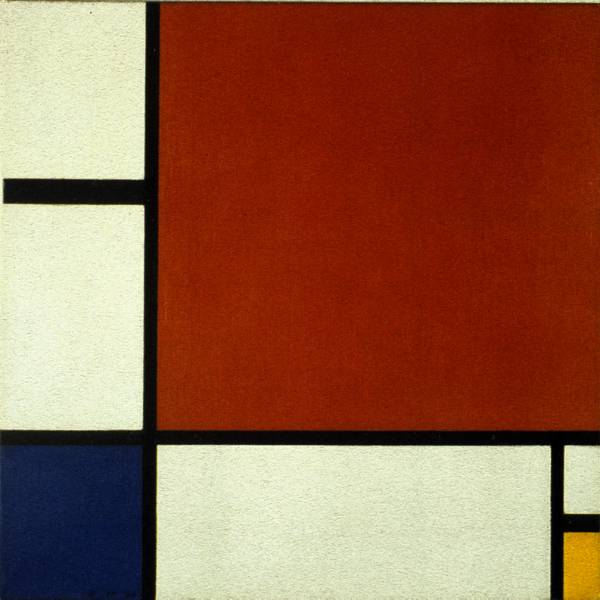

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.