“Then along came Ayler. Holy shit! Brash and bold . . . Wailing, parading Albert Ayler – Psalm-swinging, Song-singing to you. Free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty free at last.” – Hal Russell

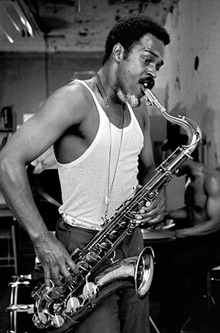

Albert Ayler (pronounced “Eyeler”), the soft-spoken but hard-blowing free jazz saxophonist took many of his devoted fans by surprise in September 1968 when he released the album New Grass (think Bob Dylan fans when he walked onto the stage of the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 with his electric guitar!).

Ayler was a leading proponent of the “New Thing” (or “Free Jazz” or even “Great Black Music” as it was variously called) being explored by fellow-saxophonists John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, trumpeter Don Cherry and others in the 1960s.

Born into a musical family in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, in July 1936, he played in his mid-teens with R&B singer Little Walter Jacobs and after graduating from High School he joined the US Army and played in the regimental band. While in the army Ayler jammed with other enlisted musicians, in particular with drummer Beaver Harris and sax player Stanley Turrentine. After his discharge from the army his music was already moving out of the mainstream and into very different places.

The difference and perceived “difficulty” of Ayler’s playing meant he got little work, especially in the US. He found a slightly better reception in Europe where he spent a lot of time, touring and playing in Scandinavia and France in particular.

Musically he was both going forward into the spaces indicated by John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman and at the same time digging deep into the old roots of jazz in the blues and New Orleans-style group improvisation.

His explorations lead him into experimentation with timbre more than harmony and melody, making his music sound furious, and yet his own tender feelings were injected into the sound, making it simultaneously lonely, sad. Having said that, melody was incredibly important to Ayler and he used it largely for its own sake rather than as a springboard for improvisation, returning again and again to the main lines of any melody, working on them to bring out every nuance of meaning.

Ayler’s commitment to the new sounds was total and his fans, small in number, but growing, were also deeply committed.

Like Coltrane Ayler was deeply spiritual and his songs reflect that. Also like Coltrane, Ayler saw music as a spiritual calling, a way to overcome evil in the world – hence his song “Music is the Healing Force of the Universe.”

Valerie Wilmer quotes Ayler in her book As Serious as Your Life (Serpent’s Tail, 1992):

“My music is the thing that keeps me alive now. I must play music that is beyond this world. That’s all I’m asking for in life and I don’t think you can ask for more than just to be alone to create from what God gives you.”

In his published recordings up to that September of 1968 Ayler was making music more and more “beyond this world,” so the release of New Grass with its R&B flavoured music complete with backing singers was a great shock to his devoted followers.

Because the album seemed to be a retreat in many ways from his explorations of the outer limits of the music the album was quickly dismissed by fans and critics as indicating a “sell out” by the great man.

Because the album seemed to be a retreat in many ways from his explorations of the outer limits of the music the album was quickly dismissed by fans and critics as indicating a “sell out” by the great man.

While it is true the album does not achieve some of the depth of his earlier (and many of his later) albums, I think it is another aspect of the trajectory of his development. After all, he had in his teenage years spent two summers touring with an R&B outfit and the blues were etched into his soul.

The album was also perhaps on a personal level something he had to do. Always spiritually searching he felt he had, as he put it in an interview in 1970, to “give the American people another chance” to appreciate his music.

So when producer Bob Thiele asked him to do an album with pop musicians Ayler agreed, but on his own terms. As he put it in the interview, “if I have to play pop music let me get the men together and play the music.”

New Grass opens with a typical Ayler wail on the tenor and then he does a short spoken introduction in which he says of the music on the album that it is “of a different dimension in my life” and he adds a plea – “I hope you will like this record.”

And he ends with a reiteration of his spiritual message: “We must restore universal harmony … we must have love for each other.”

The six songs on the album were composed by Ayler in collaboration with, among others, his companion of the time Mary Maria Parks.

The musicians on the date were a combination of R&B and rock musicians which gave the album a very different sound than Ayler’s usual output, although his tenor with its characteristic broad vibrato still seems at home.

As for “selling out” to commercialism as has been suggested by some critics, I really don’t think this album would ever be a commercial success – the music is still too raw, the emotion too real and up front, for it to be widely accepted in a “pop” way.

And yes, Mr Ayler, in spite of the critics, I like this record!