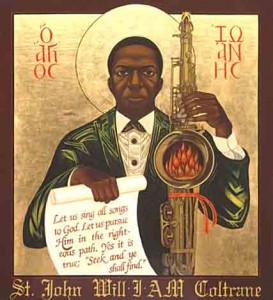

Enough energy to power a spaceship

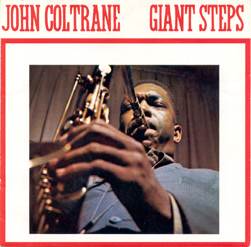

One of the greatest talents among many great talents on Miles Davis‘s seminal album Kind of Blue was tenor man John Coltrane and he also produced an outstanding album which broke new jazz ground in1959: Giant Steps .

One of the greatest talents among many great talents on Miles Davis‘s seminal album Kind of Blue was tenor man John Coltrane and he also produced an outstanding album which broke new jazz ground in1959: Giant Steps .

“Trane” as he was affectionately called, came from Hamlet in North Carolina, where he was born in September 1926. He moved to Philadelphia in 1943 and joined the US Navy in 1945. He played in a Navy band in Hawaii for about a year. He played with Davis from 1955 to 1957, with Thelonius Monk in the later part of 1957 before rejoining Davis in January 1958.

The stint with Monk was critically important for Coltrane as playing with Monk encouraged him to play more riskily, with higher levels of alertness to what was going on around him musically: “I learned new levels of alertness with Monk,” Coltrane told writer Nat Hentoff. “If you didn’t keep aware of what was going on, you were lost.”

It was also during this time with Monk that Coltrane developed the style which critic Ira Gitler would dub “sheets of sound” to describe how Trane would fit many, many notes into each bar, each phrase.

Monk also started Coltrane off on his habit of playing long, long solos.The anecdote about Davis asking Trane why he didn’t stop a solo is indicative. Trane said he didn’t know how to end the solo. “Take the mouthpiece out of your mouth,” said Davis.

Hentoff records how one of Trane’s solos could last an hour. Few other tenor players could keep up the physical demands of such long solos, never mind the ability to produce fresh ideas and sounds over such extended periods. As Gitler remarked: “His continuous flow of ideas without stopping really hit me. It was almost superhuman. The amount of energy he was using could have powered a spaceship.”

Also while with Monk Trane began to explore the limits of music in terms of both rhythm and harmony. With his only album as leader for Blue Note Records, the 1957 release Blue Train , he introduced into jazz the so-called “Coltrane changes” as two of the numbers on the album used this technique, namely “Moments Notice” and “Lazy Bird.” This technique of chord substitution would be a major feature of the Giant Steps album two years later.

The recording sessions

Giant Steps is the first album to contain only compositions by Coltrane and no standards, though five of the original seven tracks could be considered to have become standards by now, i.e. “Giant Steps”, “Naima”, “Cousin Mary”, “Countdown” and “Mr P.C.”

The album was recorded in four sessions on 26 March, 4 May and 5 May, and the final session on 2 December 1959. The personnel on each session was slightly different with Paul Chambers on bass the only constant beside Coltrane. In the original version of the album the takes from 26 March were not released, and were only released as alternative takes on the later re-releases in 1974 (the album Alternate Takes , Atlantic) and the 1995 Rhino release John Coltrane: The Heavyweight Champion, The Complete Atlantic Recordings .

In this Hub I will only be discussing the tracks from the original release. I will also not go into technical detail about the “Coltrane changes” – maybe the subject for another Hub?

The Atlantic album was produced by famed Turkish producer and Atlantic executive Nesuhi Ertegun.

The tracks in order

Track 1: Giant Steps

Animated sheet music for “Giant Steps”

The first track is “Giant Steps”, recorded on 5 May 1959 with Tommy Flanagan on piano and Art Taylor on drums.

The composition is based on a cycle of major thirds from B (it starts with a B triad) through G to E flat. According to some writers Coltrane was interested in this form by the bridge in the Richard Rodgers song “Have You Met Miss Jones?” Whatever, it is a medium tempo romp with wonderful solos first from Trane, followed by Flanagan in a relatively short one.

The next track is “Cousin Mary” recorded in the same session. Longish solo by Trane followed again by Flanagan for a few choruses and then a typically eloquent bass solo by Chambers before Trane comes back to wrap it all up.

The next track is “Countdown” which is based on a harmonic inversion of Davis’s tune “Tune Up” and is rich in “Coltrane Changes.” It is a fast, swinging number which starts with a drum intro which, after a few bars, Coltrane makes into a drum and tenor duet for a few more bars before the bass and piano come in to take the number into a swinging conclusion.

The track entitled “Spiral” is a medium tempo number recorded on 4 May, as was “Countdown.” Again the first solo isTrane’s, followed by Flanagan and Chambers, before Trane re-enters to put a seal on it.

“Syeeda’s Song Flute” is a happy medium tempo composition inspired byTrane’s then 10-year-old daughter. A very accessible jazz tune.Flanagan takes a long, happy-sounding solo, with some wonderful basslines from Chambers, who has his own also longish turn after a chorus or two, and before Trane comes back to round it off.

Track 6 is the gentle, beautiful “Naima”, named for Coltrane’s first wife. Hentoff, in the original liner notes wrote: “There is a ‘cry’ – not at all necessarily a despairing one – in the work of the best of the jazz players. It represents a man’s being in thorough contact with his feelings, and being able to let them out, and that ‘cry’ Coltrane certainly has.”

Naima was recorded in the 2 December session with Wynton Kelly on piano and Jimmy Cobb on drums.

The piece is a quiet rumination in complete contrast to the next number,”Mr. P.C.” which was recorded in the 5 May session. This is an up-tempo tribute to Paul Chambers, of whom Trane is quoted by Hentoff as saying: “I feel very fortunate to have had him on this date and to have been able to work with him in Miles’ band so long.”

Flanagan has a long, sprightly solo before Trane and Art Taylor have a session of trading fours and then Trane re-introduces the theme to bring the proceedings to an exciting end.

Conclusion – the legacy of the album

Of the many great jazz albums recorded in 1959 this is one of the most interesting and certainly has been long regarded by jazz musicians as the “gold standard” in improvisation, both in terms of the beauty of the results and in terms of the technical demands the music makes on the soloist.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2012