“Jack Spurling was the pilot who sailed many a pretty clipper ship through memory straits and anchored her again before the eyes of those who knew her best and loved her most.” – from the Sydney Morning Herald of 30 September 1933: obituary of Jack Spurling written by “Redgum”.

Born John Robert Charles Spurling on 12 December 1870 he preferred to be known simply as “Jack”.

As a youngster he haunted the London’s East India Docks at Blackwall near his parent’s home where he sketched the ships he saw there.

“Redgum” in the Obituary quoted above mentions an incident when the young Spurling, always “nosing” around the ships in the docks, was asked by the captain of the ship “Mermerus”, Captain Cole, what he was doing.

Spurling replied, “I like to watch the men at their work. Some day, sir, I hope to go to sea.”

Captain Cole allegedly told Spurling to “keep away from ships, for, as sure as God made little apples, they will get you.”

Luckily the young Spurling did not take the captain’s advice and a few years later went to sea aboard the “Astoria” bound for the East.

In Singapore Spurling fell from a yard arm and sustained injuries which necessitated a long stay in hospital and when he was discharged he joined the Devitt and Moore company, eventually gaining his second mate’s ticket. He then joined the Blue Anchor line as a second mate and did service in steamships in the colonial trade.

After some seven years at sea Spurling left to join the theatre where he was kept busy in the musicals of impresario and theatre owner George Edwardes, who in turn worked with Richard D’Oyly Carte and the famous light opera composers Gilbert and Sullivan.

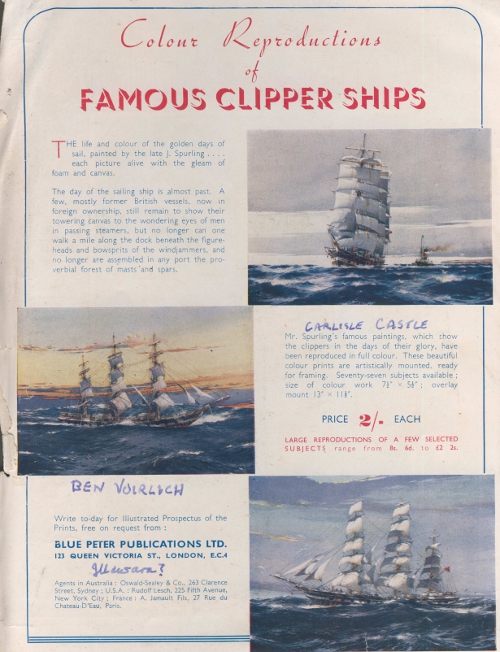

Advertisement in “Blue Peter” for the Spurling prints. Annotations by my late father Murray McGregor who was passionate about ship recognition.

His paintings came to the attention of the editor of the shipping journal Blue Peter, Frederick Hook, who placed several in the magazine where they attracted a great deal of favourable reaction from readers. Hook then commissioned Spurling to contribute more paintings for the journal, which also proved extremely popular, so that the journal in the 1930s offered 77 of Spurling’s paintings as “artistically mounted, ready for framing” colour prints at two shillings each.

The most famous and popular of the tall ships were the tea and wool clippers which Spurling painted with unparalleled skill. Indeed he was renowned for being exceedingly accurate in his depictions of the riggings of these ships.

The editor of the Blue Peter offered a reward to anyone who could fault the rigging on one of Spurling’s paintings – the reward was never paid.

Two of the most famous ships painted by Spurling were the “Thermopylae” and the “Cutty Sark”. “Thermopylae” was built in Aberdeen, Scotland, and launched in 1868. She was built for the Aberdeen White Star Line and was designed to be very fast in order to get tea from China to London in as short a time as possible for her owner, George Thompson. Getting the tea from China to London quickly was good business and turned a tidy profit for the owners of tea clippers.

A rival of George Thompson was the former sea captain turned ship owner John “Jock” Willis who wanted a ship to beat the “Thermopylae”. He got marine architect Hercules Linton of Glasgow to design a ship to beat “Thermopylae”. This ship was to become one of the most famous sailing ships of all time and was launched in November 1869 and christened the “Cutty Sark”.

Spurling’s 1924 painting of “Thermopylae”. “The picture shows ‘Thermopylae’ sheeting home the fore lower topgallant sail in a strong breeze” (from the “Blue Peter” caption to this picture).

Nannie chased Tam on his horse Maggie but only managed to pull Maggie’s tail off. The ship “Cutty Sark” was designed to pull the tail off the “Thermopylae”!

These two famous ships were engaged in a famous race from Shanghai to London in 1872 – actually the only time they were to race each other.

The “Thermopylae” got to London first as the “Cutty Sark” lost her rudder and had to go into Table Bay for repairs which took 13 days. However, she reached London just six days after “Thermopylae” and was declared the winner because of the speed which she had achieved – some 17.5 knots.

Spurling, apart from the accuracy with which he painted the rigging of the tall ships, was also able to create a sense of drama in his paintings, especially in his treatment of the sea in various conditions.

As “Redgum” wrote in his obituary of Spurling: “Only the groans of the ships and the howl of the gales beat him. Whatever could be drawn he would set down.”

Apart from his treatment of the sea – which is always superb – his paintings usually have some intriguing details like the clothing of the sailors or a flock of seagulls whirling around the stern of a tall ship at full speed with all sails set.

By the time he died on the last day of May 1933 – or as “Redgum” put it rather poetically, “dropped below the horizon a little before nightfall” – Spurling had a reputation among people who love ships and the sea somewhat akin to that of his near-contemporary and fellow seaman John Masefield who was to become, after some time spent (though much less than that spent by Spurling) “before the mast”, the Poet Laureate of Britain and who’s poem “Sea Fever” is well known:

“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking.”

I imagine that Spurling, at the end of his life, would have appreciated the last two lines of the poem: “And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.”

He certainly told many a “merry yarn” in his wonderfully evocative paintings of ships and the sea.