“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

“I believe in people, art, poetry, music, creativity and love … my art is an interaction between me and my surroundings.” – Wesley Pepper

What is the meaning of art in the South Africa of the 21st Century? Wesley Pepper is answering that question by doing art, not theorising about it.

The Johannesburg-based artist was born in Kimberley in the Northern Cape

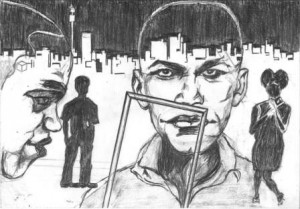

“Dark skin” – a drawing by Wesley Pepper which was included in a collection of poetry by local writers

Province of South Africa in July 1978. He studied art, majoring in oil painting and drawing, at the Free State Technicon in neighbouring Bloemfontein before moving to Port Elizabeth where he studied computer graphics at a Further Education and Training (FET) college, before moving on to Cape Town.

After a short stay back in Kimberley where he was active in an arts-and-crafts collective Pepper moved to Johannesburg in 2002.

“I sold a piece within five hours of arriving here,” he says with characteristic enthusiasm.

A concern that Pepper expresses is about the commercialisation of art: “People look at the price tag before they look at the work.”

He would like with his art to challenge the conservative world-views of many South African communities with regard to art, the conservatism of blue suits and ties!

The challenge Pepper makes is through his engagement, through postering and workshopping, through involvement with other artists, musicians and writers.

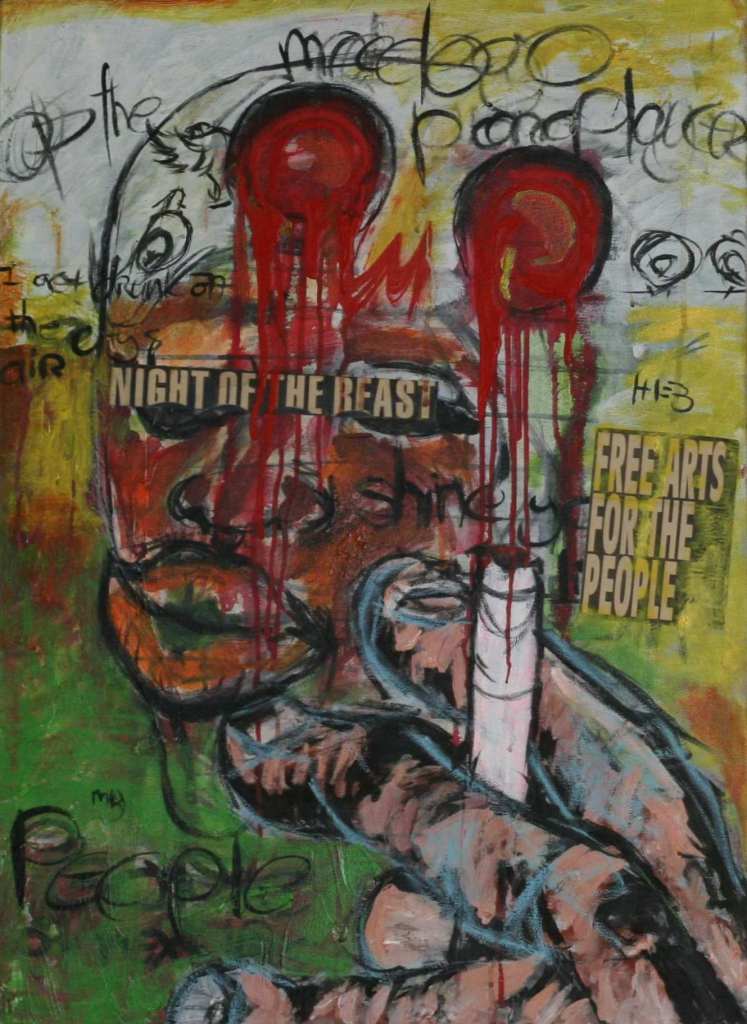

“I call my art ‘open spaces’ coz exactly of that, I involve myself in various spaces and my art is about what I experience,” says Pepper.

Together with local writers Pepper has produced three collections of poetry for which he has provided art works. He has also facilitated creativity workshops and been involved with artists’ collectives.

“I love organising people,” he says.

The collective with which he is currently involved is planning a large exhibition for 2013 – which he says will take art out of the gallery and into the street.

I asked Pepper about his views on what constitutes art, on what an artist is. His

reply: “An artist (according to me) is someone who is conscious about their creativity and has the talent to ‘make art’ and make a living off it.”

“As an artist you are measured by your work and hopefully my work made a statement and that’s what defines me.”