The albums

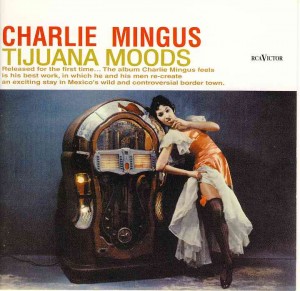

This article will look at Charles Mingus albums released in 1962, 1963 and 1964. The first of them was actually recorded in 1957, with Danny Richmond on drums for the first, and most definitely not the last, time with Mingus. This was the ever-popular Tijuana Moods , which Mingus wrote, “was written in a very blue period in my life.”

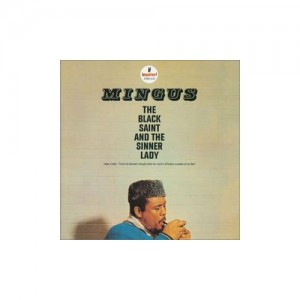

The second album is one which is very special in the whole Mingus ouvre – The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady , recorded and released in 1963.

The third album is a live album recorded at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco on 2 and 3 June, 1964. This album, called Right Now , is notable, apart from the amazing music, for the contribution of Jane Getz on piano.

Tijuana Moods

“This is the best record I ever made” – Mingus

“This is the best record I ever made” – Mingus

This album features a little-known trumpeter Clarence Shaw, who, Mingus wrote in the liner notes of the 1962 release, “by now would probably have become as famous as any of our current so-called jazz players if this record had been released six years ago when recorded.”

Shaw shines especially on the opening track, “Dizzy Moods” which is based on the Gillespie composition “Woody ‘n You”. His solo is clearly articulated and swinging, exemplifying Mingus’s comment that Shaw “doesn’t overcrowd his ideas like most improvisers. He’s like a great conversationalist, he stops and rests…” This is a typically Mingus number with frequent changes of tempo.

The next track is “Ysabel’s Table Dance” is Mingus’s successful attempt to capture his experience in Tijuana, whence he had gone to forget a break-up from his wife, and he “decided to benefit musically from this experience and set out to compose and re-create what I felt and saw around me.”

This track “contains the fire, the pulse, and all that I felt as I heard the tune in my head with the movement of her body.” A truly remarkable evocation of place and mood in jazz. The mood is greatly enhanced by the castanets played by Ysabel Morel and her vocal interjections.

Its a driving, swinging and exhilarating choice from the opening bars with Mingus’s bowed riff and the castanets setting up a fabulous rhythm which is maintained throughout. Wonderful piece, altogether.

“Tijuana Gift Shop” is a tightly swinging number with gorgeous ensemble work, featuring amazing unison riffs from Shaw on trumpet and alto player Shafi Hadi. Jimmy Knepper’s trombone growling in the background adds a great feel to the whole thing. Shaw’s muted few bars at the end are things of great beauty.

In the liner notes Mingus tells of finding himself, after arriving in Tijuana at six in the evening, “wandering through the street followed by local bands of five to ten musicians with bass, sax, guitar, and typical Spanish instruments.” That is the feeling he creates in “Los Mariachis” which, he wrote, “typifies the blues beat.” This is a gloriously atmospheric piece, alternating between hard-driving blues beat and moments of quiet, when typically just two instruments will play. In the first such break there is a superb dialogue between Shaw and Mingus himself. That is worth buying the whole album for! It’s one of those moments of total magic that sometimes happen in great music, when everything else falls away and one becomes lost in that timeless time. There are whole worlds and long beguiling stories told in this number.

The final number on the original album was “Flamingo” which is marked by an absolutely gorgeous solo from Shaw.

The final track on 2000 double CD re-issue is entitled “A Colloquial Dream (Scenes In The City)”, a great spoken poetry with music mix which was recorded in the same session as the rest of Tijuana Moods. It features the voice of Lonnie Elder, who declaims “I love jazz” and “I guess I must be the only man in the world who wakes up with jazz music!” Its a great mood piece and a fine end to the album. The words and the music are wonderfully evocative and supportive to each other. “Beautiful like a woman, a real woman,” as Elder says at the end.

Besides those already mentioned the personnel on this album include Frankie Dunlop on percussion, and Bill Triglia on piano.

The production of the two-disc re-release from 2000 that I have is great for many reasons, not least of which is the sound which is superb.

The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady

This album has been hailed by critics as having “a special place in Mingus’s work,” and “one of the greatest achievements in orchestration by any composer in jazz history.” It certainly was a very ambitious project on Mingus’s part, to write a ballet for an 11-piece orchestra, a ballet which would capture all the emotions of which his psychologist Edmund Pollock would write in the liner notes: “Mr. Mingus cries of misunderstanding of self and people.” The music does indeed, as Pollock continues, “present a brooding, moaning intensity about prejudice, hate and persecution.”

This album has been hailed by critics as having “a special place in Mingus’s work,” and “one of the greatest achievements in orchestration by any composer in jazz history.” It certainly was a very ambitious project on Mingus’s part, to write a ballet for an 11-piece orchestra, a ballet which would capture all the emotions of which his psychologist Edmund Pollock would write in the liner notes: “Mr. Mingus cries of misunderstanding of self and people.” The music does indeed, as Pollock continues, “present a brooding, moaning intensity about prejudice, hate and persecution.”

My contention, though, is that if that were all this music did it would not grab us as it does, with deep emotion, yes, but with that emotion expressed in so “right” a way, and covering a wide range of human experience, fittingly made musical in the adoption by Mingus of themes and modes from many different musics, and blended into an artistically unitary whole of immense power.

The first track “Solo Dance” is introduced by Danny Richmond opens with what Mingus describes in his 1963 notes about the album, as a “written repeated rhythmatic (sic) bass drum to snare drum to sock cymbal figure that suggests two tempos along with its own tempo.” This complexity is maintained throughout the track, through some wonderful ensemble work and a just a few solos, most notably a longer one on the alto, by Charlie Mariano, sounding like a voice “calling to others.”

The second track, “Duet Solo Dancers”, starts with a gentle piano theme, almost classical in feel, at a slow tempo, then the whole ensemble comes in with sonorous harmonies, Ellingtonian in feel (Black, Brown and Beige comes strongly to mind) In Pollock’s words, “The music then changes into a mood of what I would call mounting restless agitation and anguish as if there is tremendous conflict between love and hate.” There is an amazing muted trombone solo which again sounds like a voice calling out in anguish.

“Group Dancers” opens with some interesting piano and features some wonderful Spanish-tinged music played on a classical guitar by Jay Berliner, reminding strongly of Tijuana Moods. There are again multiple tempo changes which mirror the changing emotions. According to Dr Pollock Mingus said that the use of the guitar was meant to mirror the Inquisition and El Greco’s “mood of opppressive poverty and death.”

The final track, consisting of three movements or modes, is an even more complex piece than any of the preceding. the sub-titles of the numbers are revealing of what the music expresses: “Mode D — Trio and Group Dancers” Stop! Look! and Sing Songs of Revolutions! ; “Mode E — Single Solos and Group Dance” Saint and Sinner Join in Merriment on Battle Front; “Mode F — Group and Solo Dance” Of Love, Pain, and Passioned Revolt, then Farewell, My Beloved, ’til It’s Freedom Day. Pollock notes that “the ending seems unfinished but one is left with a feeling of hope and even a promise of future joy.”

Its a “monster” of an album, which required a very special corps of musicians to handle all the music, and Mingus had assembled a stellar cast for the recording. The personnel were, besides Mingus himself, Jerome Richardson on soprano and baritone saxes and flute; Charlie Mariano on alto; Dick Hafer on tenor and flute; Rolf Ericson and Richard Williams on trumpet; Quentin Jackson on trombone; Don Butterfield on tuba and contrabass trombone; Jaki Byard on piano; Jay Berliner on acoustic guitar; and Danny Richmond on drums.

As Steve Huey wrote on All Music (http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=A4f867ur070jd): “The result is one of the high-water marks for avant-garde jazz in the ’60s and arguably Mingus’ most brilliant moment.”

A date in ‘Frisco: Right Now

This just happens to be the first Mingus album I ever bought, back in the days of vinyl and I was living in Durban, in the South African province now known as kwaZulu-Natal and then simply known as Natal, with my family. Not sure why this particular album, but it must have sounded good to me at the time, the early 1970s, and I loved the sound and the feelings of the whole thing.

This just happens to be the first Mingus album I ever bought, back in the days of vinyl and I was living in Durban, in the South African province now known as kwaZulu-Natal and then simply known as Natal, with my family. Not sure why this particular album, but it must have sounded good to me at the time, the early 1970s, and I loved the sound and the feelings of the whole thing.

Had a bit of fun with a rather serious friend who fancied himself as a bit of an expert on classical music (to be fair, he was actually), by playing him the few bars of Mingus bowing his bass in the upper register at the beginning of “Meditation for a Pair of Wire Cutters”, the second side of the vinyl LP, and asking my friend to identify the composer. He was baffled and tried John Cage, Hindemith and a few other of the modernists, and was furious with me when I let him into the secret!

This is a wonderful album, which still sounds good to me. The first track is an updated version of “Fables of Faubus” which really cooks, as the saying goes. John Handy on alto really wails, to the great pleasure of his leader, who shouts his customary encouragement. Mingus’s own solo iks a veritable tour de force, a virtuosic display, with quotes from “Down by the Riverside” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So” woven into the swinging flow. Clifford Jordan on tenor is also inspired and uses some Coltranesque “sheets of sound” in his solo. Danny Richmond on drums is fervent and swinging and very supportive. Jane Getz doesn’t get much chance to shine but her presence is nevertheless felt. The blues with which the track ends is simply stunning..

“Meditation” starts with bowed bass introduction with which I teased my friend all those years ago. It then gets down to some serious swinging. The group on this track is without Handy but otherwise the same as the first track. Jordan gets a long solo and so does Getz. Towards the end of the track Getz and Jordan play together, he on flute, while Mingus gets out his bow again, for some interesting, almost modern-chamber music style stuff. It’s really inspired playing by all three and becomes almost atonal until the very last chord. A brilliant piece of music which in its 24 minutes covers a great range of styles and sound.

A musician of powerful originality

This ends my review of what is possibly the most creative decade of Mingus’s career, although there would still be some great albums in the years that followed, more surprises and explorations of what music is all about.

To my mind Mingus is quite simply one of the giants of 20th Century music, not just of jazz. He displayed a range of music that stretched any definition of jazz beyond the limits. No-one interested in music of any sort can really avoid the contribution of this massive genius and he certainly deserves to be taken very seriously indeed, as he demanded during his lifetime.

Nat Hentoff wrote about Mingus: “Charles Mingus was not only the most powerfully original bassist in jazz history, but he was one of the few legendary soloists and band leaders to leave an utterly distinctive body of continually unpredictable compositions. In that respect, he was in the rare company of Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk.”