The 1960 albums

The year 1960 saw Mingus record five great albums, three released in 1960, one in 1961 and one in 1980. The 1961 release was the result of his collaboration with conductor and musicologist Gunther Schuller and entitled Pre-Bird Mingus. The album released in 1980 was the live set at the Antibes Jazz Festival.

The 1960 release which will not be part of this Hub is the Candid album Reincarnation of a Lovebird, produced by Nat Hentoff, as was the album we will discuss here, Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus.

The other album we will discuss here is the live set recorded at that year’s Antibes Jazz Festival.

Mingus at Antibes

On 13 July 1960 Mingus appeared at the Antibes Jazz Festival, Juan-les-Pins on France’s Côte d’Azur, with Ted Curson on trumpet; Eric Dolphy on alto and bass clarinet; Booker Ervin on tenor; and Dannie Richmond on drums. Bud Powell joined the group for “I’ll Remember April”.

The group’s set opens with an atmospheric, swinging version of “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting”, which sounds indeed like a Holiness Church meeting, complete with shouts, moaning and hand-clapping, which generates an incredible emotional energy, especially during Dolphy’s amazing solo. A solo from Richmond is followed by a brief but exciting chorus from Curson before the whole meeting is wrapped up with another short Richmond solo just before the whole group comes together with Mingus chanting “Oh yeah, my Lord” which others take up.

“Prayer for Passive Resistance” opens with a slapped bass figure from Mingus which Richmond quickly echoes, leading into Ervin’s soulful solo.

Next comes that great Mingus number “What Love” which features great solos by Dolphy and Curson.

Bud Powell delivers a typically great solo on “I’ll Remember April”, a kind of bebop revival thing in this context. Powell’s solo is a feat of creativity – the track is 14 minutes long and the solo lasts almost half of that time. The number swings furiously throughout. and features solos by Curson, Dolphy and Ervin besides Powell. There is a long passage of play in which Ervin and Dolphy enthusiastically trade fours, building up to a great finale in which Curson also gets involved in some group improvisation before the head comes back and Powell signs it all off.

“Folk Forms No 1” is introduced by Mingus playing a funky figure before the ensemble comes in equally funkily. Ervin, Dolphy and Curson again do some great group improv with Mingus providing some enthusiastic support and playing off the others. This all generates enough energy to light up New York City, never mind the crowd at Antibes who get enthusiastically into the swing of the whole thing. Mingus’s solo on upright is enough to make any bass guitarist worried. The three horns just keep on going, playing off each other, sometimes with rhythm section and sometimes without. An incredible performance all round.

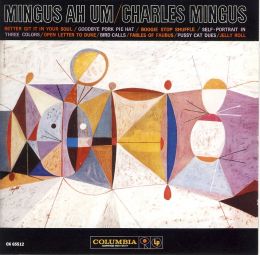

The final track is that great Mingus number we first met on Mingus Ah Um: “Better Git Hit in Your Soul”, here taken at breakneck speed and with an incredible load of energy pulsing along. It gets so breathtaking at times I keep expecting the band to collapse with exhaustion, especially seeing they had by this time been going for an hour of high intensity music, but they just seem to get higher and higher on the energy. Amazing stuff! Again the gospel feel is heightened by hand clapping and shouting, encouraging the players to ever new heights of expression.

This is an album I return to again and again, an album of really exciting, emotional music, just as Mingus said: “Music is, or was, a language of the emotions.”

Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus

This recording was a relatively rare instance of Mingus recording with a quartet – besides himself there were his current favourite collaborators in the Jazz Workshop: Dannie Richmond on drums, Eric Dolphy on reeds and Ted Curson on trumpet. In spite of Mingus’s interjections and introductions this is a studio recording and there was no audience. Mingus wanted to replicate the ambiance of a club date without the distractions of such gigs, like ice clinking in glasses and cash registers ringing. It was in fact recorded at Nola Penthouse Sound Studios in New York City

The first track is listed on the cover as “Folk Forms No 1”, but Mingus seems to have been a bit unsure about the title in the actual performance, he calls it “Opus”, or “New Series 1”, “Folk Series”. Whatever, it is a swinging vehicle for each of the collaborators to shine, which the leader and Richmond proceed to do, each taking longish solos. Mingus introduced the number as being based on “folk song form” and if jazz can be termed a “folk form” then it surely is.

The next number is listed as “Original Fables of Faubus”, perhaps a wry reference to the banning of the lyrics from the “Fables of Faubus” track on the Columbia album the previous year. Mingus dedicates the piece to “the first, or second, or third all American heel”:

Oh, Lord, don’t let ’em shoot us!

Oh, Lord, don’t let ’em stab us!

Oh, Lord, don’t let ’em tar and feather us!

Oh, Lord, no more swastikas!

Oh, Lord, no more Ku Klux Klan!

The next number, “What Love?” featuring a great solo by Mingus and otherwise very similar (with, of course, a smaller force!) to the arrangement on Antibes. It’s a great tune and gives especially Dolphy a chance to really shine on that bass clarinet! Great stuff.

Mingus introduces the next track as “a tribute to all mothers.” I’m not sure if he means “mothers” in the jazz sense, but whatever, it has a ridiculous title (must be one of the longest in jazz): “All the things you could be by now if Sigmund Freud’s wife was your mother.” Yes? Even Mingus admits “it means nothing.”

What it is, is a another Mingusian (how’s that for a made up word?) romp at high speed through the changes. Curson especially makes the most of the opportunity to take some high flying liberties with the whole thing. Then Dolphy just makes mincemeat of everything with some amazing pyrotechnics, to the shouted encouragement of Mingus. It’s great fun and wonderful to listen to. I love the way the solos sound as if they cannot stop at all and then do, very suddenly. The changes in the tunes are not anywhere near those in “All the Things You Are” but Mingus apparently told his players to keep that tune in mind as they played this one. Weird idea but it makes for great fun.

The reviewer of CD Universe (http://www.cduniverse.com/search/xx/music/pid/1224780/a/Charles+Mingus+Presents+Charles+Mingus.htm accessed 21 July 2009) wrote of this album that “The songs here feature a fiery amalgam of blues, gospel, and folk with group improvisation.” Fiery it is, and like things that have been tried by fire, it is very pure Mingus, to my mind one of his best.

Ronnie Lankford, Jr is quoted on the Accoustic Sounds website (http://store.acousticsounds.com/browse_detail.cfm?Title_ID=16452 accessed 21 July 2009): “The album accomplishes what the best of Mingus accomplishes: the perfect tension between jazz played as an ensemble and jazz played as totally free.” I totally agree. It’s a blast, it’s thoughtful, it’s angry and it’s fun.