“A picture is worth a thousand words” – this is a popular and frequently-heard saying. And yet it cannot be taken at face value. Philosophers and artists have during the past hundred years or so argued about the purpose and content of art, ever since art theoreticians like Roger Fry, Clive Bell and Herbert Read contended that art should not convey any message other than the formal contents of the work of art itself, the form, line, colour, texture of the work itself.

These three philosophers of art were reacting to the extreme sentimentalisation of art of the Victorian era, where art became the servant of “prettiness” and bland subjects that did not require any depth of thought but just a superficial reaction of pleasure, much like what we would today call “comfort food” gives us when eaten – no nourishment for body or mind, just a pleasant taste.

Which brings us to the question of the “purpose” of art – or does it not have any purpose outside of itself? What would life be like without beauty around us? What is beauty?

Painting of bisons in the caves at Lascaux

Indeed there is also the question, “Is art good for us, or bad for us?” The Puritans and some fundamentalists would argue that art is a distraction which takes our minds of the serious business of life, and feel this so strongly they would ban it from any places where this seriousness is pursued, like places of worship or work.

The answer given by such people gives us a clue that art has an impact, quite a big impact, on our lives. The earliest people made paintings and drawings of sometime haunting power on the walls of caves, depicting the life around them and their responses to that life, practical or spiritual. They clearly needed to surround themselves with these images, the images enriched their lives in some way, they invested these images with meaning which could not be gained in any other way.

Likewise mediaeval monks in their monasteries created works of art in the manuscripts that they wrote out, embellishing the words with exquisite miniatures of scenes from life or myth, which added to the meaning of the words themselves. Clearly these monks in the otherwise austere lives found these embellishments not only added to the manuscripts but to their own lives as well.

With the dawn of the modern era in the 19th Century art became more and more separated from this kind of context and came to be pursued as “art for art’s sake.” This is a concept which would have been unthinkable to the cave artists or to the monks creating those magnificent manuscripts.

From the Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius

In the 20th Century this was taken to extremes, but perhaps necessary extremes, when one thinks about the poor, meaningless stuff that was favoured by the Victorians, the “comfort food” type of art.

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

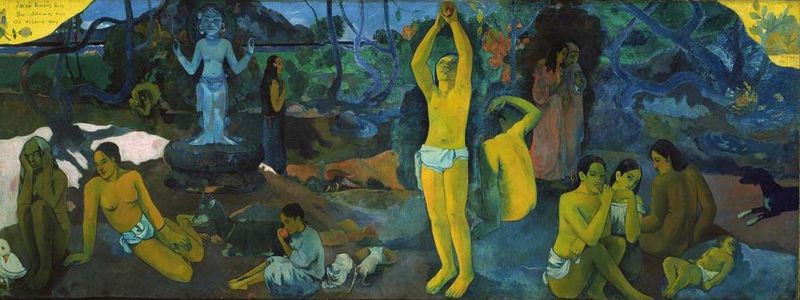

So what is meaning in art? Another artist, Paul Gauguin, painted a huge canvas which also took on the issue head on. This painting is frankly philosophical in intent: “I have completed a philosophical work on a theme comparable to that of the Gospel,” he wrote to his friend Daniel de Monfried in 1898. He called the painting “Where have we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” and the painting was large, like its theme. It measured six metres in length and almost two metres in height.

Gauguin had high aspirations for the philosophy expressed in this painting, which he saw as having a definitive and moral result, “the liberation of painting, already freed from all its fetters, from that infamous tissue knotted together by schools, academics, and above all else by mediocrities.” It is a painting dense with meaning, but the meaning needs to be teased out, it cannot be simply assumed. It is, in Herbert Read’s words, “a correlative for feeling and not an expression of feeling.”

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?

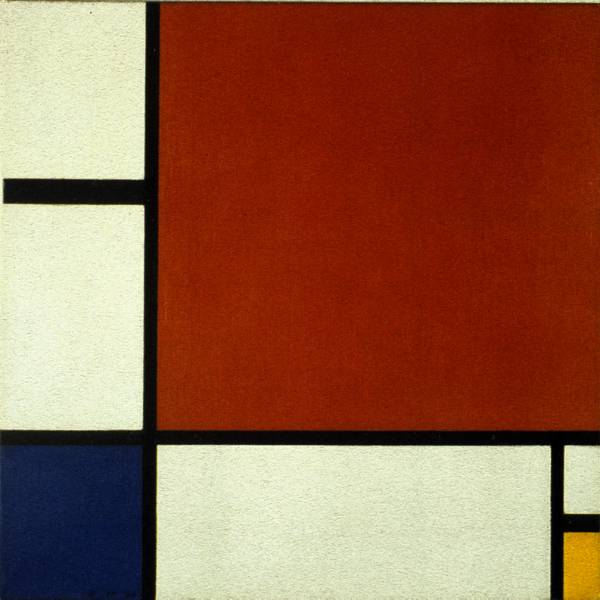

This painting would seem on the surface at least to be light years away from paintings such as those of Piet Mondrian, which are simply grids made on the canvas by lines of grey or black, with the spaces between filled with white or primary colours, seemingly at random. These paintings cannot be “read” like a story, so what are they about, what do they mean? Mondrian called his style “neo-Plasticism” and it related to the neo-Platonic “positive mysticism” of Dutch philosopher (Mondrian was also Dutch) M.H.J. Schoenmaekers and the teachings of the Theosophical Society. This philosophy was an attempt to penetrate the reality behind nature and to give it expression. As Herbert Read said of Mondrian’s approach, “Art becomes an intuitive means, as exact as mathematics, for representing the fundamental characteristics of the cosmos,” (in A Concise History of Modern Painting, Thames and Hudson, 1959).

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

The viewer’s life and understanding is therefore enriched by contemplating the work of art and connecting his or her experience and situation to that of the artist. This is no “comfort food” but good, wholesome, hearty fare, well-cooked and needing to be thoroughly digested for the goodness to be available to the consumer. And like such wholesome food, time and effort put into the contemplation is rewarded with a sense of completion, of healthy and lasting fullness, quite different from the quick and transient satisfaction which comes from “comfort food”.

Speak Your Mind