In his short, sad life he was controversial. More than 100 years after his death, he seems not much less controversial. But he still manages to weave a spell for anyone interested in art, particularly Art Nouveau and the art of illustration.

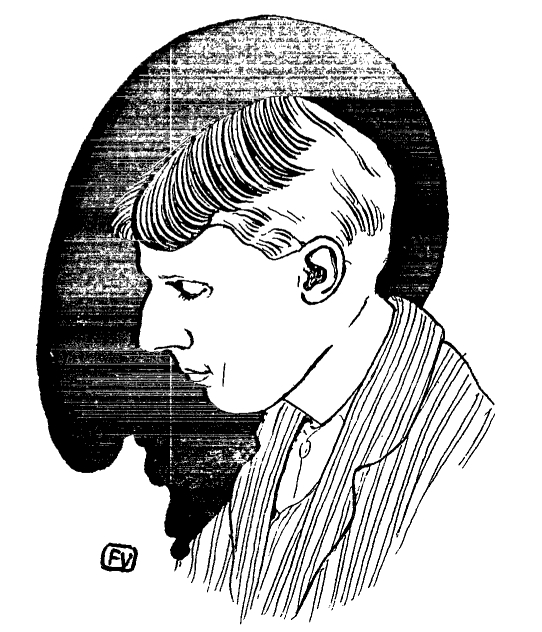

Beardsley by Valloton

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley, dubbed by his contemporaries, often not too kindly, “Awfully Weirdly”, was born on 21 August 1872 in Brighton, England. His mother, Ellen, was the daughter of a Surgeon General of the Indian Army and his father, Vincent Paul, the son of a tradesman.

Aubrey’s family moved to London in 1883 and he was soon thereafter sent to Bristol Grammar School where he wrote and performed in a play with some of his fellow-students. He also at that time started to draw, and some of his cartoons were published.

In 1892 he began to study art at the Westminster School of Art, having been advised to take up art seriously by Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir Edward Burne-Jones and French artist Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes.

Two things which made Beardsley so controversial were his strange, unconventional drawings and his intense interest in sex, at a time when the society in which he moved was still extremely Victorian, prudish in matters of sex, to say the least. His style flouted the norms of “decent” society, society which could accept art which amounted to the erotic so long as it was cloaked in conventional, usually “classical”, forms.

As critic and editor Derek Stanford has written (in his introduction to Aubrey Beardsley’s Erotic Universe, Four Square, 1967), “Working in black-and-white, he brought to this narrowly limiting medium an immense resonance of suggestion; and it is this power of suggestion which makes him the superb eroticist that he is.”

Stanford explains why Beardsley was, and still is, a haunting, perplexing artist, whose images still have the power to hold the viewer’s attention, and stay in the memory long after they have been looked at.

The reason is that Beardsley is an eroticist par excellance, but not a pornographer.

There is always debate around the difference between the two, and Beardsley is an excellent subject with which to explore the difference, as he produced works which could be called erotic, indeed, the bulk of his output tends to be in this category, but he also produced a small number of clearly pornographic images, mainly in support of a play, Aristophanes’ Lysistrata which was published in 1896.

Stanford explains the difference between erotica and pornography thusly: “The pornographer’s business is solely to state; even in his fantasies he must be literal. In contrast, the erotic artist conveys his effect largely by suggestion. And what he suggests must be more than the erotic fact itself.”

In 1997, William J. Gehrke, then chairperson of the MIT Lecture Series Committee, explained the difference between pornographic and erotic films in this way: “Pornographic film has as its primary purpose the graphic depiction of sexually explicit scenes. It generally depicts these scenes in a way that is degrading to women or, less frequently, to men. It tends to perpetuate the myth that rape and sexual assault are appropriate forms of behavior. Erotica, on the other hand, seeks to tell a story that involves sexual themes. Sexually explicit scenes in these films serve a secondary role to the plot. Erotic film displays sexually explicit scenes in a more realistic and equal fashion that is not degrading to either gender.”

Beardsley’s work provides nice examples of the fine line that exists between the merely obscene and the high art of the erotic.

Beardsley contracted tuberculosis at age seven, and his struggle with ill health dominated his life. As Matthew Sweet wrote in The Independent of 15 March 1998, “Sex was a profound influence on Beardsley’s work, on the company he kept, and on the progress of his illness.”

Beardsley died in France on 16 March 1898, having been received into the Catholic Church the year before. He was 25 years old, and as far as anyone knows, still a virgin, despite his intense interest in all matters sexual. There was a rumour that his sister Mabel and he had had an incestuous relationship, but this was never proven.

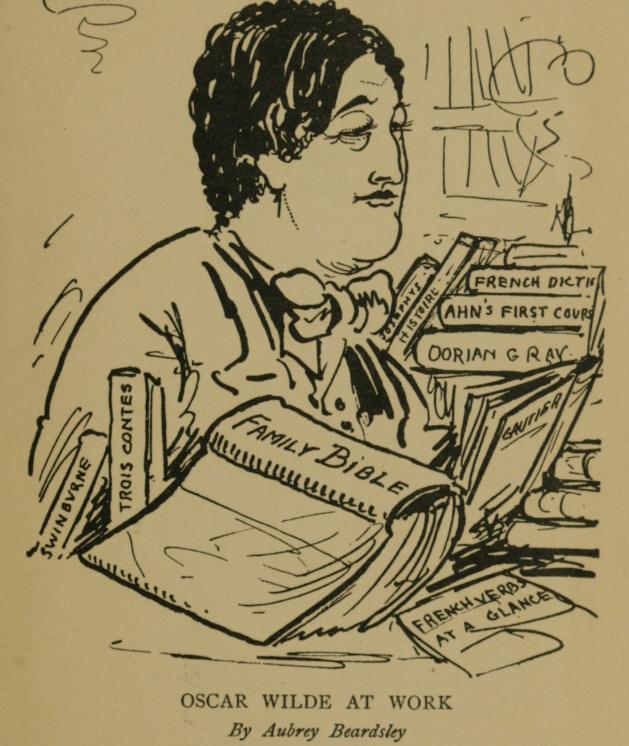

Oscar Wilde by Beardsley

Although he kept company with known homosexuals, including Oscar Wilde, it is fairly certain that he was not himself homosexual.

For one who was so sickly and whose life was so short, Beardsley managed to produce a large number of works of art of unquestionable value and great, if sometimes strange, beauty. And in his short lifetime he managed also to have a great influence on Art Nouveau and the art of illustration.

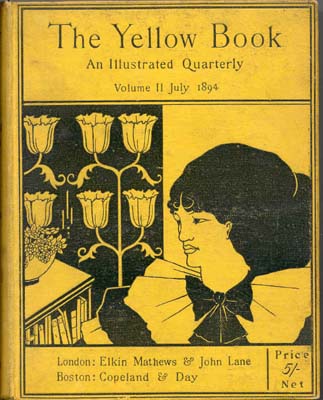

Beardsley was associated with various publications including the Yellow Book, a famous British literary and artistic journal of the 1890s. Many of the leading artists and writers of the day were published in this journal, including Max Beerbohm, Arnold Bennett, George Gissing, Henry James, H. G. Wells, and William Butler Yeats .

Beardsley was associated with various publications including the Yellow Book, a famous British literary and artistic journal of the 1890s. Many of the leading artists and writers of the day were published in this journal, including Max Beerbohm, Arnold Bennett, George Gissing, Henry James, H. G. Wells, and William Butler Yeats .

In this article I will discuss only ten of Beardsley’s works, drawing on comments by Stanford.

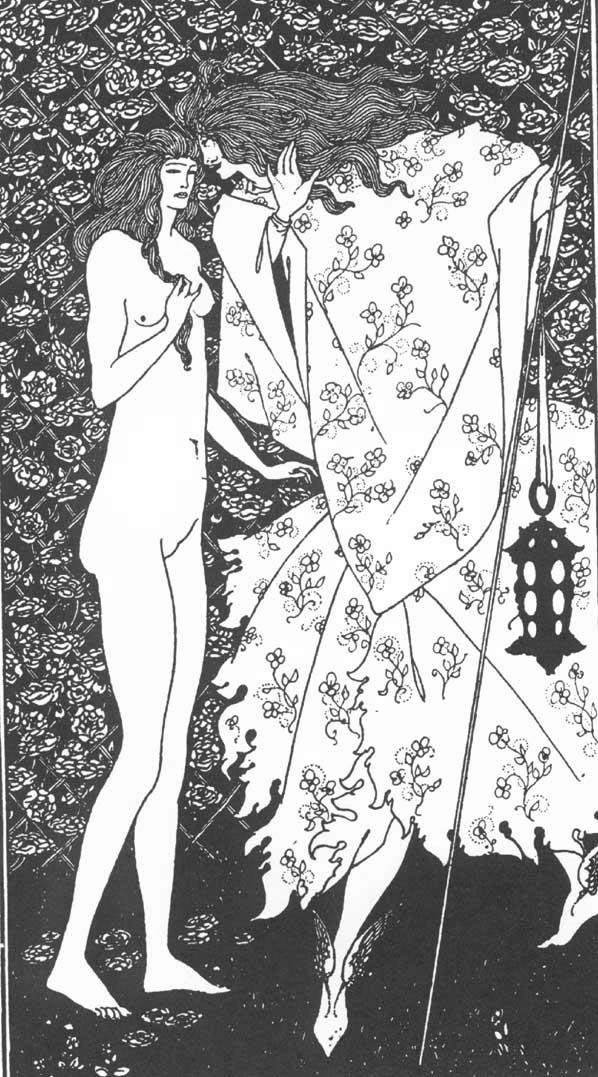

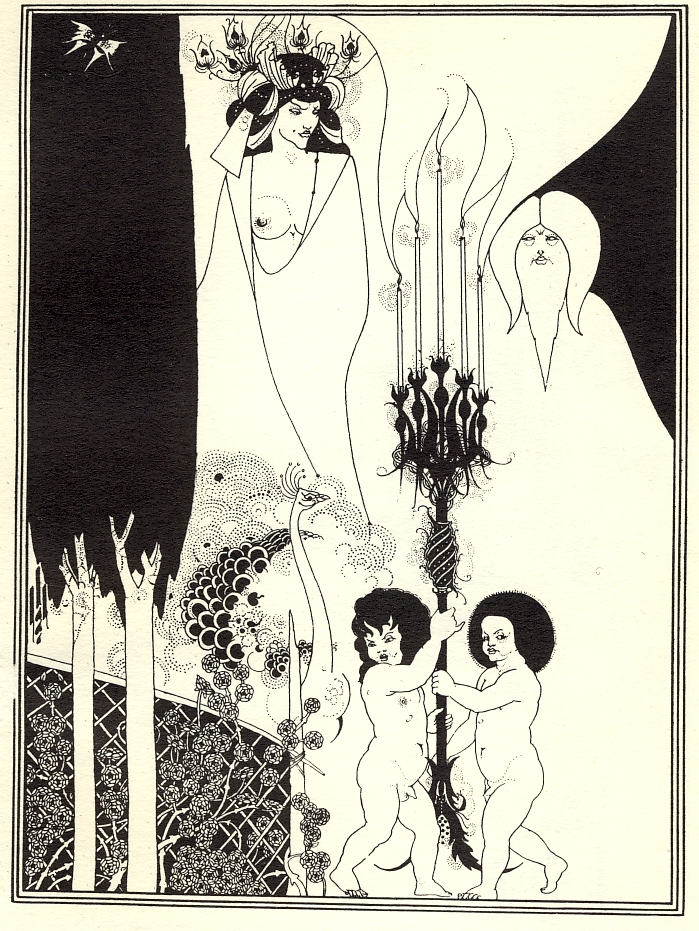

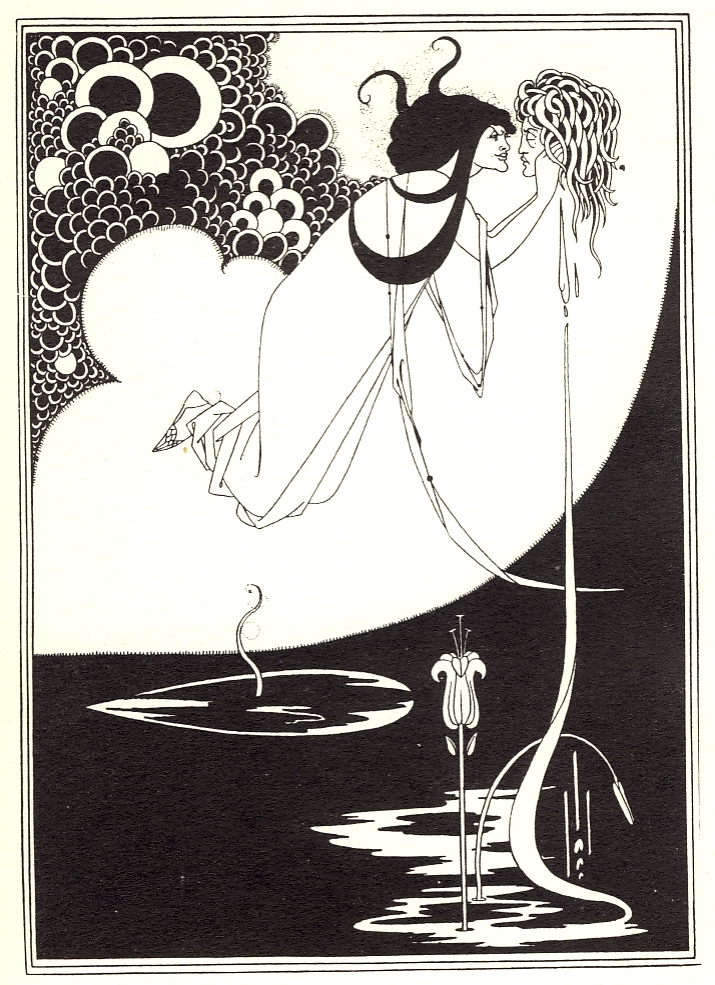

The first of these is the lovely Mysterious Rose Garden, which, according to Stanford, “conveys a sense of Beardsley’s elaborated gospel of sin.” The drawing, “is eminently successful, depending on the contrast between the naked, slender figure of the woman and the voluminously full figure of the ‘Dark Angel’ clad in a swirling loosely skirted robe and bearing his long-tipped staff and glowing lantern.” It is indeed a haunting image of great beauty and not a little disturbing for all that.

The first of these is the lovely Mysterious Rose Garden, which, according to Stanford, “conveys a sense of Beardsley’s elaborated gospel of sin.” The drawing, “is eminently successful, depending on the contrast between the naked, slender figure of the woman and the voluminously full figure of the ‘Dark Angel’ clad in a swirling loosely skirted robe and bearing his long-tipped staff and glowing lantern.” It is indeed a haunting image of great beauty and not a little disturbing for all that.

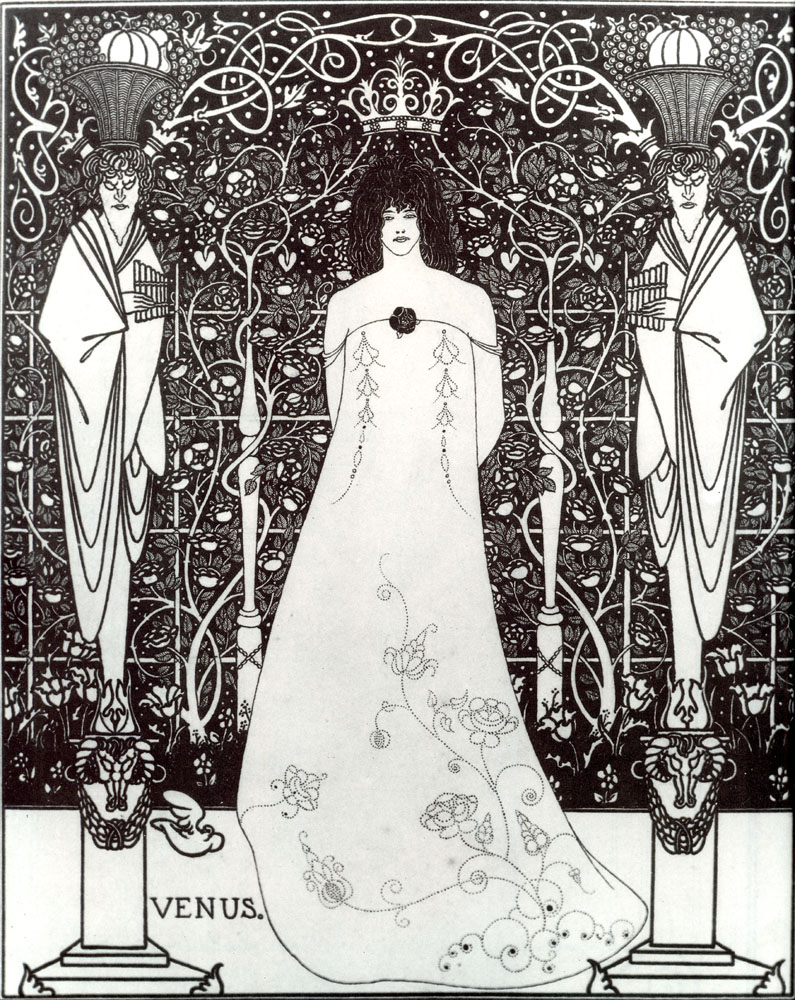

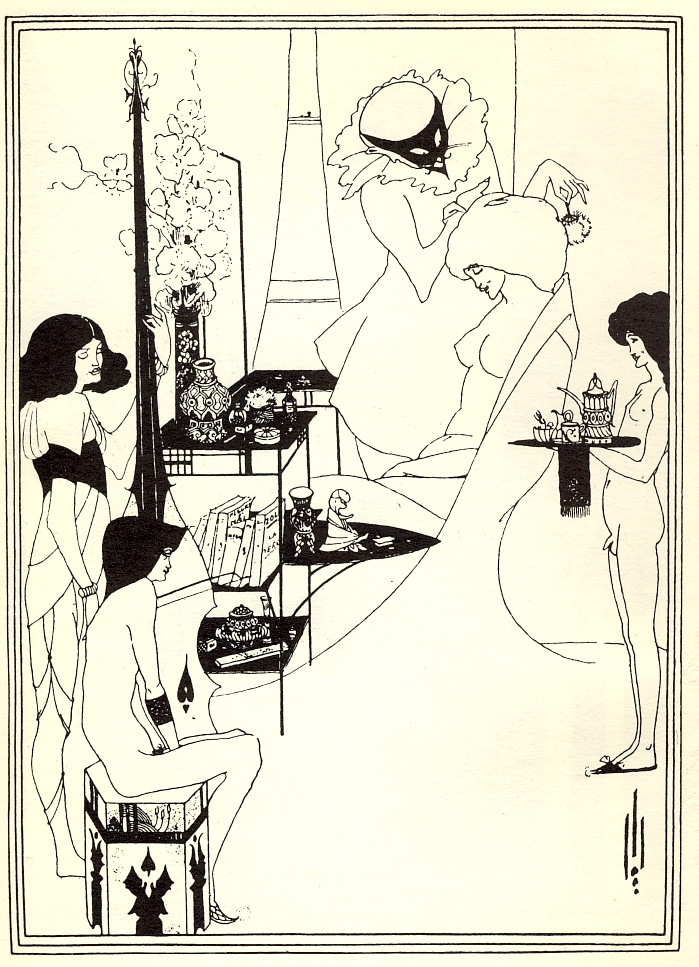

In “Venus between Terminal Gods” Beardsley’s use of what Stanford calls “disguised or concealed eroticism” is so subtle that it could easily be missed. Stanford draws attention to the floral pattern creeping up the gown of Venus “which terminates just where her thighs meet.” This illustration was to have been the frontispiece to Beardsley’s unfinished novel Venus and Tannhäuser which was published posthumously as Under the Hill, in 1907.

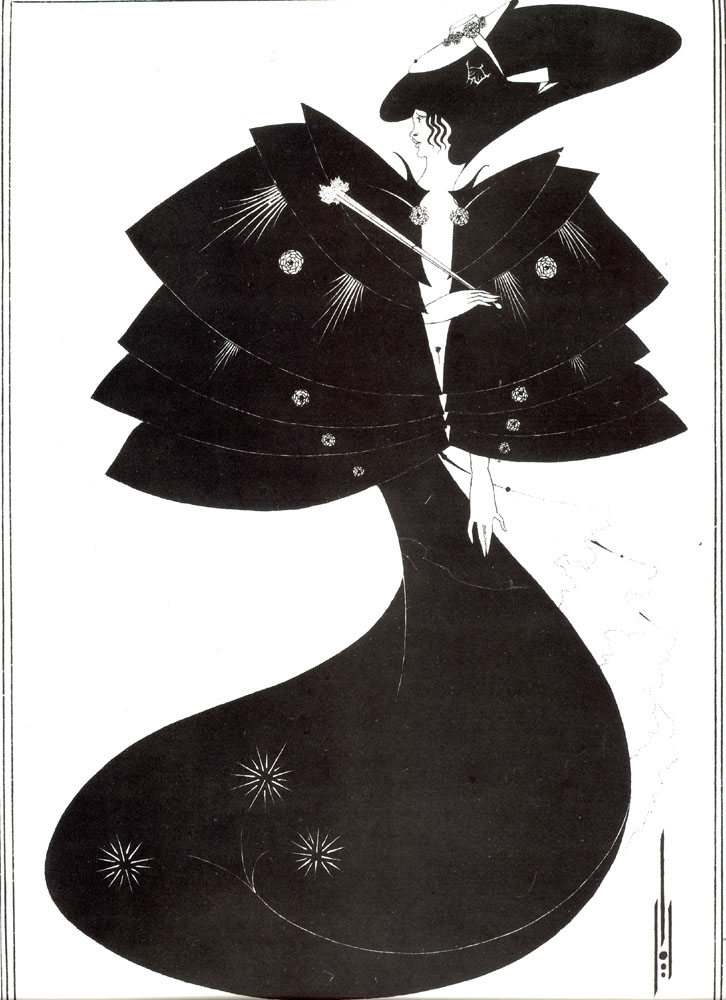

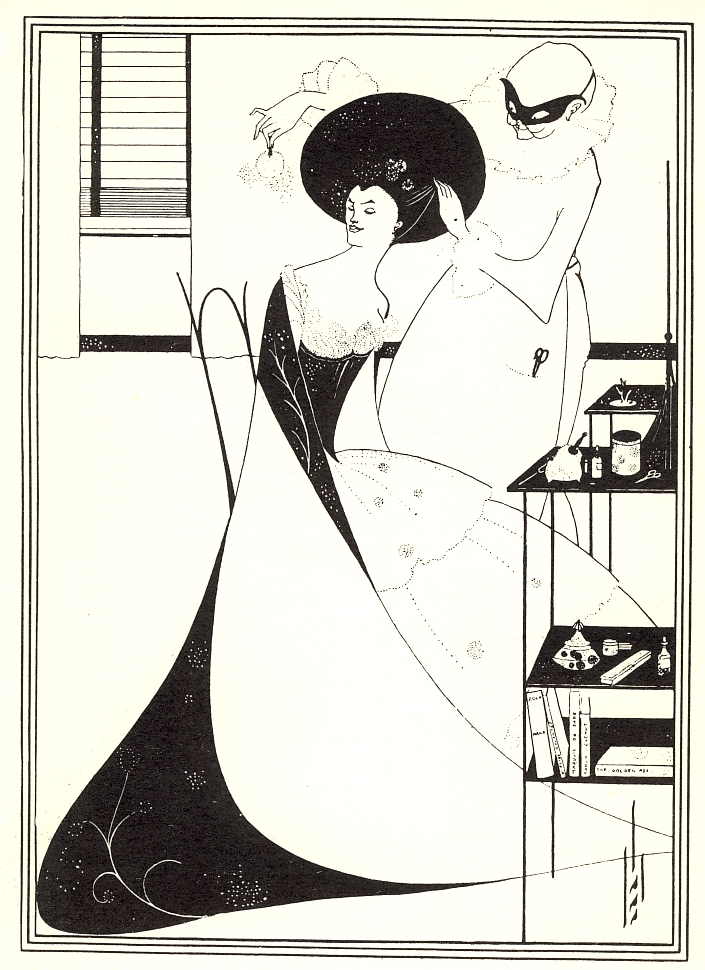

One of Beardsley’s most famous pieces is “The Black Cape”. In this work the influence of Japanese print makers is clear, even to the mark that Beardsley used as his signature. The balance and swirl of this piece is ravishing to the eye, in spite of its being in sober black and white.

One of Beardsley’s most famous pieces is “The Black Cape”. In this work the influence of Japanese print makers is clear, even to the mark that Beardsley used as his signature. The balance and swirl of this piece is ravishing to the eye, in spite of its being in sober black and white.

Beardsley had, even before his reception into the Catholic Church, a strange relationship with religion generally, and the Church in particular. His attitude was expressed in two drawings, the “Large Christmas Card”, which was a loose insertion into the first issue of the Savoy, another literary journal with which he was associated, and “The Ascension of St Rose of Lima”.

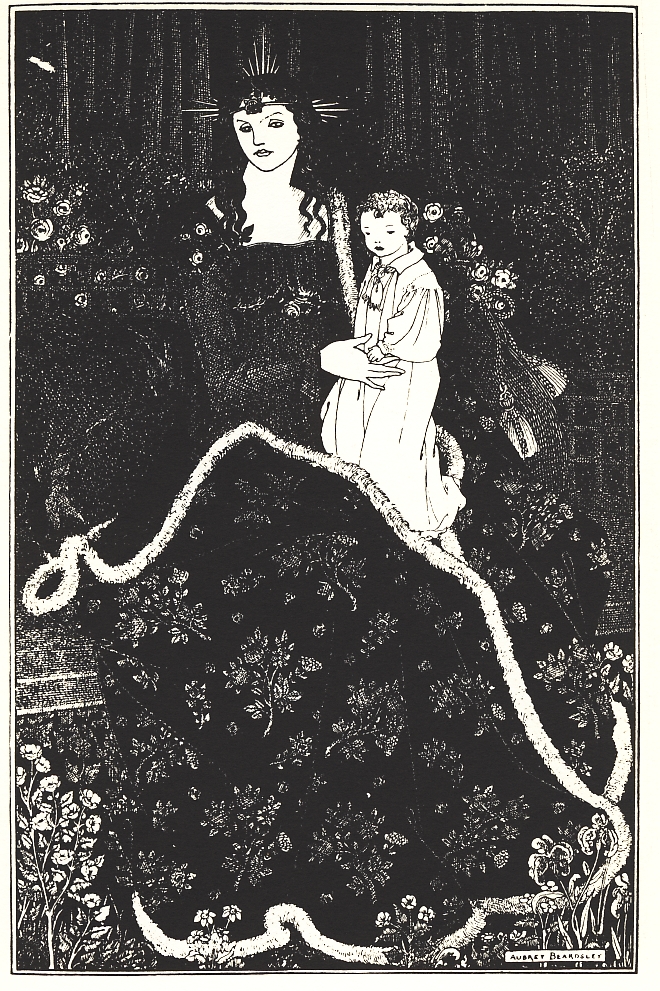

The “Christmas Card” shows an insipidly pretty Virgin holding the Holy Infant, who looks more like a very young Anglican choir boy than a new-born child. The drawing is rich in typical Beardsley-fashion floral draperies against which the face of the Virgin and the figure of the Child stand out in stark simplicity. The Virgin is given more “holy” attributes than the Child, but in spite of them her prettiness leads one to thoughts of rather more mundane than sacred love. It is, to say the least, ambiguous.

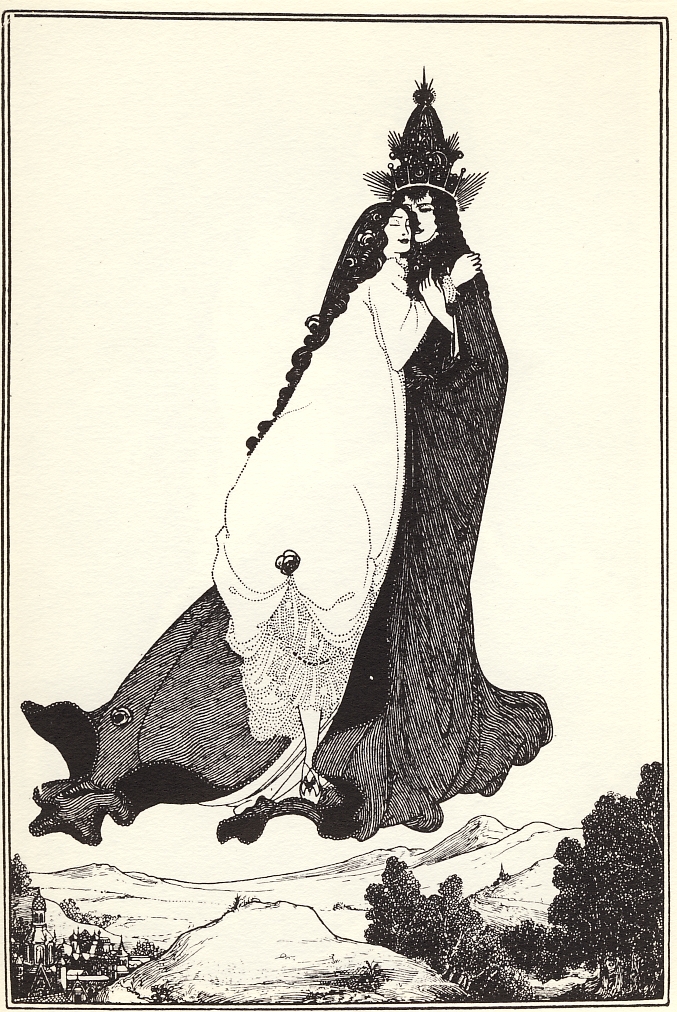

Less ambiguous is the image of love in the St Rose drawing. Here the love is clearly profane which makes the picture almost blasphemous. Indeed, in Stanford’s words, “the saint’s closed eyes and smile, in the embrace of the heavenly bridegroom, speak more of sexual than celestial levitation.”

Beardsley did a series of illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé, of which we will consider six here, the Toilette of Salomé I and II, The Eyes of Herod, Stomach Dance, the Dancer’s Reward and the Climax.

“The Tetrarch has a sombre look. Has he not a sombre look?” the first soldier in Wilde’s play asks.

“Yes, he has a sombre look,” says the second soldier. Meanwhile Herodias is becoming quite unsettled by the way Herod the Tetrarch is looking at Salomé: “You are looking at my daughter. You must not look at her. I have already said so.” This is the scene depicted in the drawing “The Eyes of Herod.” Beardsley does not leave the viewer in much doubt as to what Herod’s eyes are taking in.

The two Toilette scenes show Salomé getting ready to dance for Herod: “I will dance for you, Tetrarch.” Then, “I am waiting until my slaves bring perfumes to me and the seven veils, and take off my sandals.”

The voice of Jokanaan is heard, saying “Who is this who cometh from Edom, who is this who cometh from Bozra, whose raiment is dyed with purple, who shineth in the beauty of his garments, who walketh mighty in his greatness? Wherefore is thy raiment stained with scarlet?”

Herodias is horrified by the prophet’s words and tries to get Herod to go back into the palace: “I will not have her dance while you look at her in this fashion.”

But Salomé dances and Herod, entranced, asks her “What wouldst thou have?”

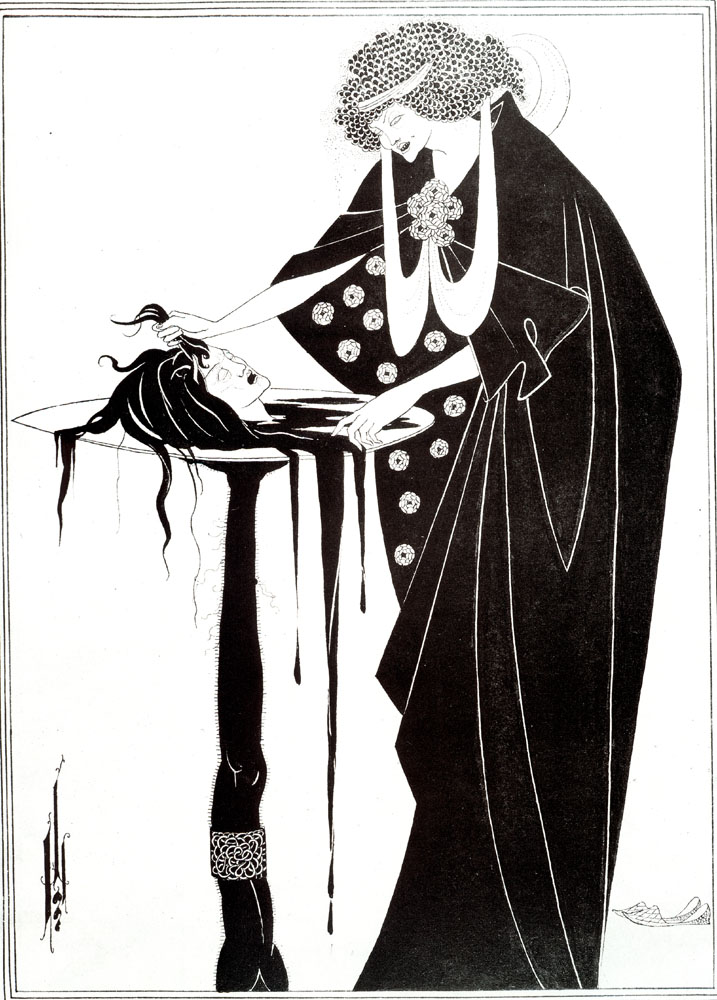

Then comes the fateful, terrible answer: “I would that they would bring me in a silver charger … the head of Jokanaan.”

“The Reward” is brought to Salomé, dripping gore, and in “The Climax” she makes to kiss the gory head: “Yes, I will kiss they mouth, Jokanaan. I said it. Did I not say it?”

A really horrifying climax in which the illustration, by its starkness captures the horror and strange fascination of it. There is in Salomé’s response the horror of necrophilia, the wild abandon to the lusts of death: “If thou hadst looked at me,” she tells the dead head, “thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.”

A really horrifying climax in which the illustration, by its starkness captures the horror and strange fascination of it. There is in Salomé’s response the horror of necrophilia, the wild abandon to the lusts of death: “If thou hadst looked at me,” she tells the dead head, “thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.”

A few minutes later Herod’s slaves kill Salomé on Herod’s order. A fittingly gory end to a gory, sadistic scene.

Is this pornographic or erotic? Is there more than a hint of sadism here?

By his juxtapositioning of the beauty of his drawings and the ambiguousness of what they appear to show, Beardsley is confronting the viewer with questions – what is good and what is evil? What is sacred and what profane? His drawings challenge us not to accept things at face value, but to dig deeper. At the very least the simplicity of medium is contrasted with the richness of what is portrayed and this causes us to look more deeply at the images.

Because of the depth of the questions raised by Beardsley the images have the power to linger in our minds far longer than the insipid acceptable paintings and drawings of the time, which have little power to hold us because in the end they are so literal. So which images are pornographic and which erotic?

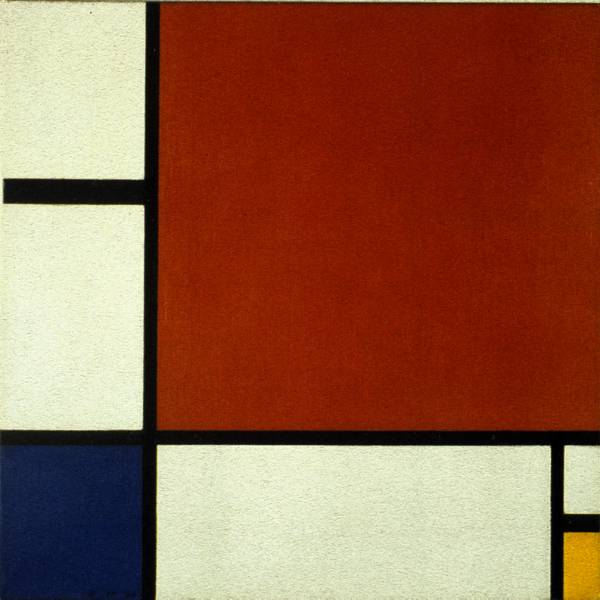

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

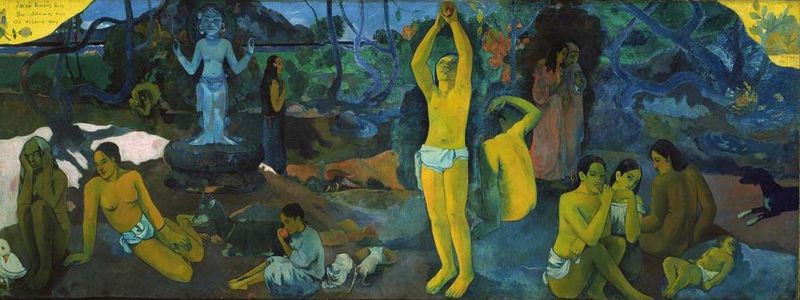

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

The past few days in Pretoria have been rainy, not the torrential rain that has plagued the Western Cape and caused such disruption, but good rain has fallen nevertheless. As always, such rain brings new life to a garden, new leaves and flowers and insects. Our small garden has become a joyful place, a place of little joys and delights that recall for me the words of Eleanor Farjeon’s popular song “Morning has Broken”:

The past few days in Pretoria have been rainy, not the torrential rain that has plagued the Western Cape and caused such disruption, but good rain has fallen nevertheless. As always, such rain brings new life to a garden, new leaves and flowers and insects. Our small garden has become a joyful place, a place of little joys and delights that recall for me the words of Eleanor Farjeon’s popular song “Morning has Broken”: The grass underfoot has indeed become springy, and a wonderful vibrant green. The trees surrounding the garden have taken on a new look, as though they have put on new clothes in honour of the arrival of summer.

The grass underfoot has indeed become springy, and a wonderful vibrant green. The trees surrounding the garden have taken on a new look, as though they have put on new clothes in honour of the arrival of summer.