Philosophy is often regarded as impractical, something separate from “real life”—whatever that might be!

Actually, as author Edward Craig writes in the interesting book Philosophy – a very short introduction (Oxford, 2002): “In fact philosophy is extremely hard to avoid, even with conscious effort.”

Craig makes this claim because, as he writes, we are all to some extent philosophers. Anyone who asks questions about values, about who or what we as humans are, about life and what it means or even if it means anything, is actually doing philosophy. And most of us ask such questions.

When a child asks us “Why?” we are being challenged to answer a philosophical question. And we all know that children are incessant askers of that question.

The relevance of philosophy to our world, to the harried, hurried world of business, of getting on or getting by, is that it helps us to think critically, consciously, about decisions and choices we make.

Without doubt the pace of modern life requires of us to make decisions very rapidly, sometimes we are even encouraged not to think too much, just to act.

Even when we have to do that, when we have to just go on and do without much prior thought, we can begin to improve our decision making skills by some thought after the event—how did that go? What are the outcomes of those actions? How can I do it differently next time to achieve a better outcome?

As soon as we do this kind of thinking we are practicing philosophy. And our decision making is improved by that practice.

While the formal study of philosophy, although it could be helpful, is not necessary, some reading that is challenging beyond simple “escapist” stuff is definitely beneficial. The brain, after all, is like a muscle—it becomes better with use.

Engaging with people is also helpful—and the more the engagement becomes interesting and useful the more we have exercised the grey matter. Like any skill, the skill of philosophy is improved with practice.

So, while sitting aloof in our own space thoughtfully stroking our beards might be for some an attractive escape from the pressures of life, the real philosophy is an engagement with life, with the people and activities around us.

Books on philosophy

Here are some suggestions of books that might help us in such engagement—and these are just some suggestions of books that I have found helpful myself:

Firstly an enjoyable read that tackles questions of values and quality is the classic from 1974 by Robert M. Pirsig: Zen and the Art of  Motorcycle Maintenance. Don’t be put off by the title – as Pirsig himself noted, it’s not about Zen and not much about motorcycle maintenance either!

Motorcycle Maintenance. Don’t be put off by the title – as Pirsig himself noted, it’s not about Zen and not much about motorcycle maintenance either!

The Oxford Very Short Introduction I mentioned at the start by Edward Craig is another fun, yet deep, read. Absolutely worth buying if you can find a copy.

The Oxford Very Short Introduction I mentioned at the start by Edward Craig is another fun, yet deep, read. Absolutely worth buying if you can find a copy.

Then there are the books by Christopher Phillips, The Socrates Cafe and Six Questions of Socrates. These are excellent books showing the practical relevance of philosophy to modern life in interesting, non-academic ways. Outstanding reads, both of them.

Finally any books by A.C. Grayling are worth looking at, though as a start I would suggest the non-academic works like The Meaning of Things and The Reason of Things (these were published in the US under the titles Meditations for the Humanist and Life, Sex and Ideas respectively).

And, if one wanted to go further, books by Albert Camus, Erich Fromm, Stephen R. Covey, and others can provide further mental stimulation and encouragement.

Philosophy is about life, and about living it to the full with conscious involvement and commitment.

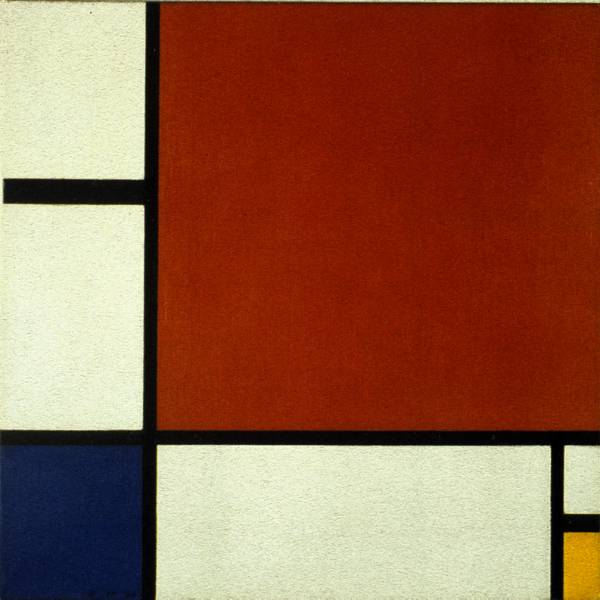

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

The ultimate challenge to the “comfort food” art was the art of the modernists like Hans Arp and the surrealists like Rene Magritte who painted a tobacco pipe and then labelled it Ceci n’est pas une pipe (This is not a pipe) and did the same with the painting of an apple. This is a direct challenge to the viewer’s normal interpretation of such a painting, or image. If asked, “What is it?” the viewer will naturally respond, “It’s a pipe.” However, clearly it is not a pipe. Asked about it the artist said “Try stuffing it.” It is an image and can be read in many different ways – it can be appreciated for the colours, the lines, the texture, the “feel” of it. But it cannot, ever, be used. Likewise the apple could never be eaten, only looked at.

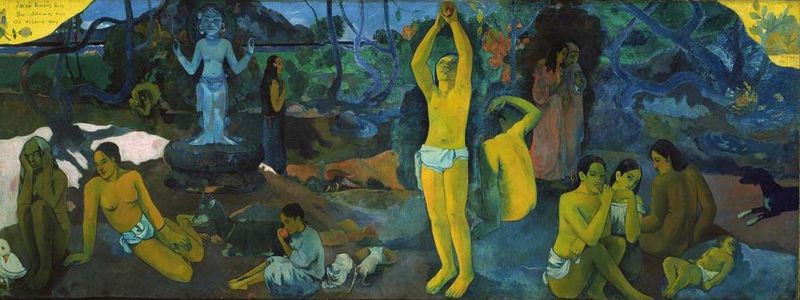

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

So while the surfaces of the two paintings are worlds apart, the meaning coming from the intentions of the artists can be seen to be related, in that both artists saw their works as having a spiritual dimension, the meaning was external to the painting, though neither literal nor literary. The paintings referred to no external “Gospel” or myth, but to the understanding of the artist.

How can whites live with the legacy of apartheid? – a moral question

Prison wall on Robben Island. Photo by Tony McGregor

South Africa has always been, in Allan Drury’s words, “A very strange society” so it should perhaps not surprise us that 20 or so years after the official death of apartheid, that strangeness still afflicts us so severely. Drury wrote his book in 1967, when official apartheid was just 20 years old. Since then the strangeness has only grown.

The 1994 settlement which saw beloved elder statesman Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela become the first democratically-elected president in our twisted history, was heralded by many as a “miracle” – and there was much that seemed miraculous. For the first time that I know of in history a ruling oligarchy negotiated itself out of power.

But that miracle had some serious flaws, flaws which are more and more coming to light as the strains of adjusting to a globalised economy and a rapidly-evolving world political scene start to take hold. The very fact that the settlement was negotiated has left us with issues that need to be resolved. Negotiation is frequently, though not necessarily always, done through compromise and letting go of interests.

Negotiations took place in the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) and the subsequent bi-lateral negotiations between the ruling National Party of President F.W. De Klerk and Mandela’s African National Congress, and then in the broader Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF) which hammered out an interim constitution for the country. In all these negotiations some critical issues were left to the future, one of them, the issue of land distribution which was greatly in favour of whites thanks to the 1913 Land Act which had made 87% of the land surface of South Africa an exclusively white preserve.

The MPNF left land tenure issues to be resolved by the so-called “willing buyer, willing seller” mechanism. By 2008 this policy had failed to resolve the land tenure issue satisfactorily and, according to Professor Ben Cousins of the University of the Western Cape, more people have lost access to land than have gained it through this mechanism. As Prof Cousins points out: “If land questions remain unresolved, the possibility clearly exists for populist politicians to focus strongly on these issues in order to build a support base, leading to unrealistic policies that promise much but fail to deliver real benefits. This in turn could lead to discontent and unrest.” (On the “Livelihoods after land reform” site, http://www.lalr.org.za/ accessed on 21 August 2011).

It is this discontent and unrest that is very visible in South Africa today, and is articulated very vividly by the former president of the ANC Youth League Julius Malema, who not long ago called whites “criminals” because they stole the land from the blacks. “They (whites) have turned our land into game farms… The willing-buyer, willing-seller (system) has failed,” Malema was reported as saying. “We must take the land without paying. They took our land without paying. Once we agree they stole our land, we can agree they are criminals and must be treated as such.” Many whites responded to these statements with defensiveness which, while understandable , showed but little historical insight.

Solomon T. Plaatje

In fact much of the land was taken by force and, in 1913, by law, when the infamous Land Act was first promulgated by the Parliament of the newly-formed Union of South Africa. This Act made a black South African, in the words of contemporary writer Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje “… not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.” That perception of pariah status reached its apogee during the apartheid era and has continued to some extent up to the present.

A disturbing result of the demise of official apartheid has been the rise of white denial of the distress caused by apartheid – the rise of people who would argue that apartheid was not that bad, that blacks under apartheid were better off than blacks in the rest of Africa, and even, to some extent, than blacks in other parts of the world, for instance, the United States.

The other side of this denialism is that the same critics use the undeniable corruption that is plaguing South Africa to discredit the ANC government and imply that blacks cannot be trusted or are naturally prone to corruption and are un-skilled or other such racist inferences.

Philosopher Samantha Rice from Rhodes University in Grahamstown asked in a recent (2009, Journal of Social Philosophy) article, “How do I live in this strange place?” Rice points out that “…an honest and sincere public dialogue about race has not yet happened in South Africa—the subject is too close to the bone for many and too much is at stake and too confused—race is the unacknowledged elephant in the room that affects pretty much everything, in and outside academia”

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu. Photo by Tony McGregor

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu recently caused some more concern among whites when he raised the issue of reparations for blacks who had suffered under apartheid – remarks which, not for the first time, caused some to call him racist. Tutu has consistently argued for more moral dialogue, for a greater commitment from whites to engage with their black fellow-citizens about issues which concern both. Tutu, however, is articulating, in more reasoned tones, to be sure, what Julius Malema is also saying – for the vast mass of blacks have up to now experienced little improvement while whites continue to live much as they did under apartheid. Whites continue to live in white areas, their children go to well-resourced schools, they have regular holidays and participate in many cultural activities. Most of these things are denied to blacks.

Now of course there is the class issue – but in South Africa class and race coincide to a very large degree and whites are seemingly in the main so habituated to privilege that they don’t see themselves as privileged, and hence the denialism, the refusal to engage in the debate but rather to minimise the negative effects of apartheid. As Rice noted, “Because of the brute facts of birth, few white people, however well-meaning and morally conscientious, will escape the habits of white privilege; their characters and modes of interaction with the world just will be constituted in ways that are morally damaging.”

So how can a white person really live a moral and authentic life in the circumstances of South Africa at the beginning of the 21st Century? Certainly not by attempting to minimise or deny the evil of apartheid. Certainly not by attempting to escape the dilemma by claiming not to have benefited from the system. Rice is rather more pessimistic than I would be about this. She states flatly “I do not think that it is possible for most well-intentioned white South Africans who grew up in the Apartheid years to fulfill their moral duties and attain a great degree of moral virtue.”

Her prescription to deal with this moral issue is that whites should adopt a demeanour of humility and silence. I agree with the humility part, but not necessarily with the silence part.

In the face of the great moral evil that apartheid represents, humility on the part of whites is most definitely appropriate. We benefited greatly from a great evil, there is no doubt about that; even though many white individuals might have struggled through the apartheid years, their struggles were not of the same order, either physically or morally, as the struggles of blacks.

From that position of humility, of appropriate contrition for apartheid, we should express our solidarity with all South Africans in the struggle for a just, more equitable society, to listen to others with openness in order to understand what they would expect from us in the struggle, to accept black leadership and initiative in these matter.

Neither condemnation nor retreat is likely to be useful. A humble engagement might help ourselves and the country more. Failure to do this, failure to commit to the struggle to overcome the painful legacy of apartheid, will in a very real sense mean forfeiting our right to stay here.