“…the evident longing of our times to understand through these delightful people the intrinsic nature of our species and of human alternatives.” – from Frontiers, by Noël Mostert.

When whites first settled at the bottom end of Africa they encountered a group of people they did not understand, a group so different from themselves they could hardly see them as human, and as a result they began to treat them quite literally as vermin.

This group of people were known by the Dutch settlers as “Bosjesmans” or “Bushmen” – people who lived in the “bush”, people who “could appear and vanish as though materializing from or dissolving into sand or grass.” (Mostert, Frontiers, p31).

This group of people were known by the Dutch settlers as “Bosjesmans” or “Bushmen” – people who lived in the “bush”, people who “could appear and vanish as though materializing from or dissolving into sand or grass.” (Mostert, Frontiers, p31).

From the 17th to the late 18th Century Bushmen, or San, as they were called by the Khoikhoi, were hunted as vermin by the settlers, and, to some extent, by the Bantu-speaking people who came into contact with them from the eastern regions of Southern Africa.

Only in the second half of the 20th Century were their real significance acknowledged and a beginning was made in an unbiased assessment of their importance in human history.

Sir Laurens van der Post, famous South African writer, published the first popular studies of Bushmen in his books The Lost World of the Kalahari (1958) and The Heart of the Hunter (1961). These books promoted a kind of “noble savage” image of the San, a highly-romanticised vision of them.

A very different view is that taken by photographer Paul Weinberg in his wonderful book In Search of the San (The Porcupine Press, 1997), a collection of Weinberg’s highly evocative photos linked by his commentary on his trips to Bushmen settlements in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana spanning the years 1984 to 1996.

In an introduction written by Riaan de Villiers the gut-wrenching reality of Bushman life in the late 20th Century is put into the context of the conflict between development and conservation.

The Bushmen suffered displacement on a large scale by the development of nature reserves and the destruction of the conditions which made their lifestyles viable. Some Non-Governmental Organisations are helping the Bushmen adapt to a market economy and to develop the skills needed for survival in the 21st Century, including the development of art schools and retail outlets for their arts and craft.

But, as De Villiers notes, “…these trends do not mitigate the dispossession of the Bushmen, and should not serve to obscure it. The vast majority continue to drift further and further away from their culture as they struggle to survive.”

Weinberg noted in his entry for Tjum!kui in Namibia: “At the weekend, social dislocation reaches a crescendo. Ghetto blaster rule: men and women alternate between traditional rhythm,s and township jive. Alcohol takes its toll; some people pass out, others fight. The modern world and a stone-age culture have met – with dire results, it seems.”

One of those dire results is the continuing exploitation of Bushmen and their culture as tourist attractions. Weinberg relates how a group of Bushmen in Kagga Kamma reserve near Ceres in the Western Cape are used to provide the illusion of Bushman culture: the advertising brochure reads “Enjoy a trip with the small people. Participate in an informal experience with a Stone Age culture.”

Admittedly, for all the inauthenticity of the experience, the Bushmen themselves are better off in this set up – Weinberg notes that the clan’s “standard of living has improved dramatically,” because they are able to keep the proceeds of sales of their crafts and have land on which to farm with chickens and turkeys.

The book is full of such interesting and insightful reading, mercifully free of the kind of sentimentalising that so often comes into writing about the San.

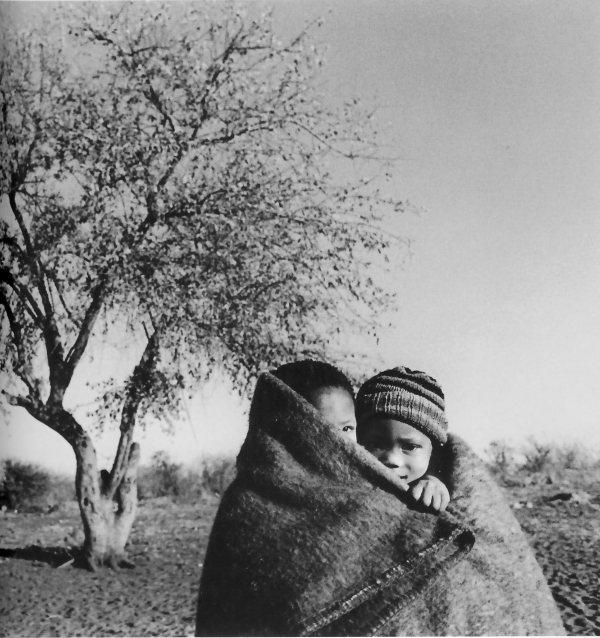

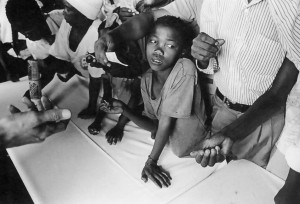

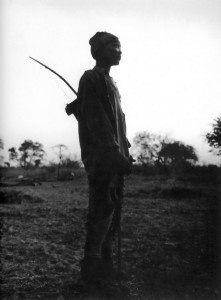

The main impact of the book is made by the superb photos which, in documentary style, show the contemporary lives of Bushmen in all their many facets – from typical hunting to drunken fights, from cute children to army recruits.

There is a richness in the images which helps the observer to get a strong sense of the impact of the collision of the modern world on the culture of what was a hunter-gatherer culture, and the impact is not always pleasant.

Another aspect brought out by the book is the fact that the Bushmen are not a homogeneous group – there are many different clans or groups which speak different languages and have different cultures.

The book is not a “coffee table” book and neither is it an anthropological text – though it has aspects of both. It comes across mainly as one person’s response to a continuing unfolding of a changing culture – a culture which in many ways provides a link between the reader’s time and a time in the almost unimaginable past.

As Weinberg notes in a sort of foreword: “I join a long line of outsiders who have studied, filmed or photographed Bushmen over the past 100 years or more. With these image, I hope to depict a once harmonious culture in a state of flux and struggle. I hope they bring the reader closer to the real San of southern Africa.”

The book, and espcially the photos, is a constant reminder that people, however we might classify them, remain people with their own sense of dignity and worth. The Bushmen are not tourist attractions but real people with the needs and wants of all people for respect, understanding and involvement. In that Weinberg has achieved what he set out to do.