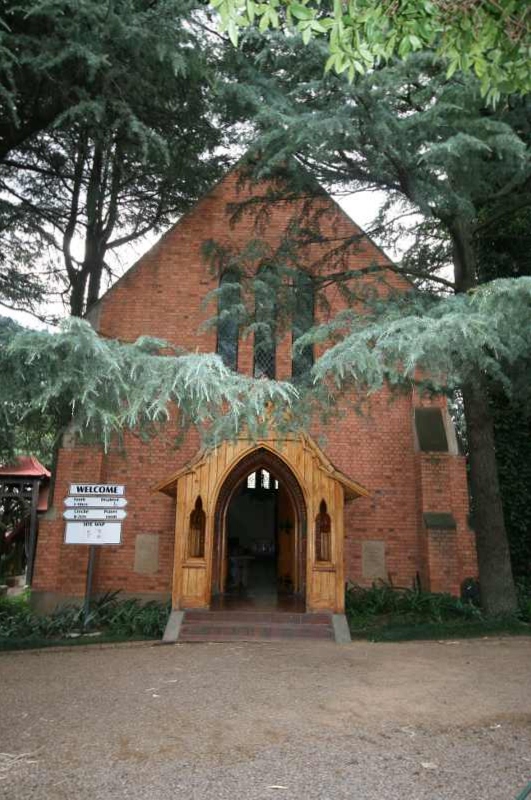

Echoes of a Victorian theological controversy which played out in the British Natal colony are heard in the Presbyterian Church of St Saviour’s in Midrand, Gauteng.

In 1853 Anglican divine and mathematician John William Colenso was appointed Bishop of Natal by the then Metropolitan Bishop of Cape Town, the Right Reverend Robert Gray. Colenso came to his new bishopric, centred on St Peter’s Cathedral in Pietermaritzburg, in 1854 and was quite soon involved in controversy around two issues – the first was his liberal interpretation of certain Biblical texts and the second was his, for the times, radical approach to the black people of the colony, the amaZulu of King Cetewayo kaMpanda.

Bishop Colenso’s views on these matters, especially his Biblical

liberalism, brought him notoriety (or fame, depending on one’s point of view) throughout the English-speaking world. The High Church party in Britain was particularly worried about the theological and political ramifications of Colenso’s opinions and Gray in December 1863 deposed Colenso after a church trial for heresy.

Colenso successfully appealed against this action but he was opposed by the Dean of his Cathedral, Dean James Green who on Colenso’s return left St Peter’s with his followers and set up a parallel Church in St Saviour’s in 1868.

Another Bishop was appointed by Gray, Bishop W.K. Mcrorie, who took his throne in St Saviour’s. Thus for a number of years there were two Church of England dioceses in Natal Colony, a situation which only came to an end after Colenso’s death in June 1883.

The two church buildings however continued to function, with St Peter’s being an ordinary parish church, until St Saviour’s was de-consecrated in 1976 and set for demolition in 1981.

Two men associated with the development of a residential township on the historical former farm Randjesfontein in Midrand, Gauteng, Charles Lloys Ellis and Keith Parker, heard of the imminent demolition of St Saviour’s and decided to buy the sanctuary, transepts, nave, chapter room and library and transport the fabric to Midrand. Here the former Cathedral was re-built under the guidance of architect Robert Brusse.

The re-constructed church is beautifully simple and elegant, retaining much of the Victorian Gothic of the original. The roof is high with lovely Gothic-style trusses and the floor of red tiles is also remarkable.

On one side of the nave is an organ loft and on the other a small baptistry chapel. The entrance to the church looks still very much as it did in 1870.

St Saviour’s, Randjesfontein, was consecrated for worship on 16 May 1985 – appropriately, the Feast of the Ascension.

The church is surrounded by beautifully-maintained gardens shaded by high conifers.

The building is still privately-owned and is rented to the Midrand Presbyterian Congregation. The beauty of the building has also ensured that is popular as a wedding venue and a venue for musical recitals and other cultural activities.

A gallery of more of my photos of this beautiful church can be found here.

Atomkraft? – nein danke!

A man looks over the expanse of ruins left by the explosion of the atomic bomb on in Hiroshima, Japan. (AP Photo)

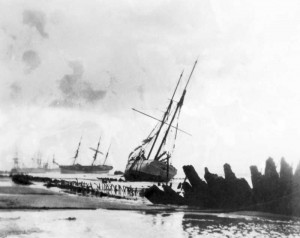

A group of schoolgirls were helping clean the streets of Hiroshima at about 08h16 on Monday, 6 August 1945, when a B-29 Flying Fortress flew high overhead. Their teacher drew attention to it – “There’s a B-san (Mr B)” and they looked up at it.

In seconds, their world, and the worlds of hundreds of thousands of others in that Japanese city, had been irrevocably turned upside down, and for many the world had simply come to an end.

There was a blinding flash of light which brought darkness to thousands in seconds after the bomb dropped by the B-29 detonated some 580 metres above Hiroshima.

It was the birth of a totally new chapter in the long history of humanity – a chapter which is still being written, and the denouement of which is still in doubt.

Albert Einstein put it well: “…the unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophes.”

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima caused an estimated 40000 deaths related to ionising radiation injuries, in addition to the

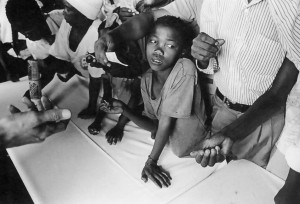

Formation of keloidal scars on the back and shoulder of a victim of the Hiroshima blast. The scars have formed where the victim’s skin was directly exposed to the heat of the explosion’s initial flash. (U.S. National Archives)

90000-odd deaths from the fires that raged after the detonation, and some 86000 injuries. The after-effects of the bomb were felt for many years afterwards with higher than normal cancer rates in survivors, and miscarriages and abnormal births at higher than normal rates among those exposed to radiation in utero.

Just three days later Nagasaki also was hit by an atom bomb, causing some 76000 deaths.

Since the bombs were dropped those dreadful August days in 1945 there have been many nuclear accidents both to nuclear power plants which have proliferated, and to bombs, though no nuclear bomb has been dropped in anger since 1945.

Atoms for peace?

The Chernobyl plant after the accident. It has been enclosed in a concrete “sarcophagus” built to last 20 to 30 years. The effects of the accident will be around for centuries

One of the major concerns about nuclear weapons and the so-called “peaceful” use of the power of the atom is the disposal of used nuclear fuel which typically is radioactive and so potentially very harmful to life.

This harmful potentiality typically lasts for a very long time – the half-life of some nuclear fuel can be up to 10000 years, during which time it has to be kept in tightly-controlled high-security containers to prevent harmful leakage.

How can we be sure in the long term that these containers will remain safe, or even that people centuries from now will really understand the dangers contained in them.

In the short term, the security needed to protect these containers is possibly not too compatible with democracy. It will take a high degree of authoritarianism to control access to these containers, which will be made more urgent by the danger of terrorist use of such materials.

Atomic energy is also often touted as a “safe” alternative to coal or other sources of energy but this I believe is not at all so. As physicist Amory Lovins has said: “Nuclear power is the only energy source where mishap or malice can destroy so much value or kill many faraway people; the only one whose materials, technologies, and skills can help make and hide nuclear weapons; the only proposed climate solution that substitutes proliferation, major accidents, and radioactive-waste dangers.”

The Fukushima accident of 11 March 2011 is an example of the risks to people and environment. Although it is not as great a calamity as the 1986 Chernobyl accident in the Ukraine it is still likely to be decades before the area surrounding the plant is decontaminated. Many lives have been irrevocably changed due to the effects of the accident.

Fukushima and Chernobyl give us a foretaste of what a nuclear holocaust could be like, and such a holocaust is by no means a distant possibility. With the levels of nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors around the world such a holocaust, though not an imminent likelihood, is certainly a possibility, especially as much of the nuclear weapons and reactors are located in politically volatile areas of teh world like the Middle East and the Indian sub-continent, China and the Democratic People’s Repbulic of Korea.

“A republic of insects and grass”

Bumper-cars in the Chernobyl fair grounds, one of teh most polluted parts of the town. Photo by Sophia Walker

Author Jonathan Schell painted a frightening picture of what such a nuclear holocaust could look like in his very informative book The Fate of the Earth (Picador, 1982), originally published in The New Yorker.

It is not a pretty picture at all.

The first sentence of the book lays the foundation: “Since July 16, 1945, when the first atomic bomb was detonated, at the Trinity test site, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, mankind has lived with nuclear weapons in its midst.”

Since that time successive governments of the United States, Russia and Great Britain, among others, have attempted to control the proliferation of these weapons. The numbers of nuclear warheads is not known accurately, nor is anyone fully certain which countries have such weapons.

What is certain is that however many there are, the effects of a war in which nuclear weapons are widely used would be calamitous to humanity and most other life forms, possibly excluding only insects and grasses, as Schell titles one of the chapters of his book.

As Schell wrote: “These bombs were built as ‘weapons’ for ‘war’, but their significance greatly transcends war and all its causes and outcomes. They grew out of history, yet they threaten to end history. They were made by men, yet they threaten to annihilate men.”

Perhaps as frightening is the realisation that has grown since Chernobyl and especially Fukushima, that nuclear weapons are not the

Nature has been reclaiming the abandoned town. Wild boars roam the streets at night. Birch trees have been shooting up at random, even inside some apartment blocks. Photo by Phil Coomes of the BBC

only things that threaten humanity with extinction. The effects of the Chernobyl accident are still being felt and the area around the plant is still a no-go area with radiation levels far exceeding what is safe for people or other animals. The accident was directly responsible for 56 deaths on site, but the fall out necessitated the evacuation of 350000 people and damage to property in the region of $7 billion. An estimate states that a further 4000 could still die as a secondary result of the accident. The town of Prypiat and the plant itself are abandoned yet still present threats which necessitate constant surveillance of the area.

At Fukushima the effects are also terrifying, and will continue to be for years. The tsunami-caused accident has been described by one nuclear energy expert, Arnold Gundersen, as “the biggest industrial catastrophe in the history of mankind.”

An October 2011 study found that Fukushima was “the largest radioactive noble gas release in history not related to nuclear bomb testing.” The nobel gas involved is Xenon-133 which is not absorbed by humans or the environment.

At the same time, hot spots of radiation are being found 60 to 70 kilometres away from the plant, further away than those from Chernobyl.

Since the start of the atomic era there have been an estimated 99 accidents at nuclear power plants, 56% of them in the United States. Considering the risks and potential damage caused by such accidents, especially the long-term effects, this is not a promising fact.

As one observer, journalist Stephanie Cooke, has written about Fukushima, in reaction to those who claim that nuclear power is “safer” than conventional power generating plants:

The way ahead: allies of death or of life?

Children in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine have been suffering from the effect of the radiation released in April 1986. The Rechitsa orphanage in Belarus has been caring for the huge population of sick children. Photo Credit: Julien Behal/Chernobyl Children’s Project

Schell, in his book writes about the “two paths” which lie before humanity: “One leads to death, the other to life. If we choose the first path – if we numbly refuse to acknowledge the nearness of extinction, all the while increasing our preparations to bring it about – then we in effect become the allies of death, and in everything we do our attachment to life will weaken; our vision, blinded to the abyss that has opened at our feet, will dim and grow confused; our will, discouraged by the thought of trying to build on so precarious a foundation anything that is meant to last, will slacken; and we will sink into stupefaction, as though we were gradually weaning ourselves from life in preparation for the end.”

This is the discussion, the conversation, we as members of the great human family, must have if we are to be allies of life ionstead, if we are to, in Schell’s words, “break through the layers of our denials, put aside our fainthearted excuses, and rise up to cleanse the earth of nuclear weapons.”