“We were on a coast of centuries of sea tragedies, and of millennia of prehistoric habitation. A great deal of the strange and incomprehensible surrounded one there, and one was credulous of many things that one would not believe elsewhere. Such belief is a form of affirmation of that sense of wholeness that is so distinctively African, and upon which I have several times remarked, a purity of bond with the unfathomable, the unknowable and the long reach back that reduces the human immediate to a great littleness. It was what I chose to remember throughout the writing of this book.”

These final sentences of Noël Mostert’s great, wonderful book Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (Pimlico, 1992) are really a summing up of the experience of reading this long and absorbing book. There is so much in this book of the unknowable, of the “long reach back”, and the final littleness of our human existence.

These final sentences of Noël Mostert’s great, wonderful book Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (Pimlico, 1992) are really a summing up of the experience of reading this long and absorbing book. There is so much in this book of the unknowable, of the “long reach back”, and the final littleness of our human existence.

On one level the book is a chronicle of the incredible arrogance of white encroachment on black existence, the piecemeal and yet dogged conquest and appropriation of the land which the Xhosa-speaking peoples of the Eastern Cape regarded as their ancestral birthright.

At another level the book is an exploration of humanity, of what makes us human, what leads us to forget our common humanity, and so the book rises above mere history to become a philosophical meditation on the human condition, and especially on that condition in the South Africa in which we find ourselves in the early years of the 21st Century.

On this level the Frontiers of the title are not only the moving borders on the colonial map but also the interface between two civilisations – the white European and the black African. On this “frontier” the missionaries who came to “civilise” the black people in South Africa were key, and highly controversial, players.

The missionaries mostly brought a high Victorian sensibility to their work among the Xhosa-speaking peoples, which caused misunderstanding and conflict. The attempts at “civilising” the blacks meant that the missionaries became associated with the colonising forces in the eyes of the Xhosa-speaking people, and their message of salvation was treated respectfully but critically. This “frontier” remained largely intact even as the lines on the map shifted and changed.

In a sense, if we want to understand South Africa now, this book is essential reading. If we want to understand our fellow-citizens in this strange land, black and white, this book will deliver deep insights.

Mostert, Cape Town born and of a long line of ancestors stretching back to the early white settlement of the Cape in the mid-17th Century, is a masterful writer who manages to hold attention while delivering masses of information; drawing on a wide variety of sources his narrative has a weighty authority.

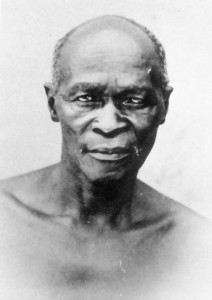

From the background of the broad sweep of the historical events colourful characters abound who stand out and command attention. There is the frontier giant at almost seven feet tall Coenraad de Buys who married many women (none of them white) and fathered a people, the Buysvolk of the northern parts of South Africa; there is the very human and yet very interesting James Read (Snr) who came to South Africa fired with enthusiasm to uplift the “Hottentot” (Khoikhoi) people and lived as one of them, marrying a Khoikhoi woman and championing their cause against the white settlers; there is the brave and ultimately tragic chief Maqoma who in the end wanted nothing but to live like a white farmer; the little braggadocio governor Sir Harry Smith who, understanding almost nothing of Xhosa culture, claimed himself to be their “Paramount Chief”; there is the sad chief Sarili who had a deformed leg and was regarded by many as a weakling, but who was the “last great independent chief of the Xhosas” and whose final tragedy was to be the chief over the great cattle killing of 1856 which brought about the end of the Xhosa-speaking people’s independence.

As Mostert notes, in spite of the way the British had treated his father and his people, “…there had never been anything in Sarili’s demeanour that suggested a hatred or a longing for vengeance. He appeared in every respect to be a larger man than that.”

Sarili, as he comes through in this great book, epitomises the tragedy of the Xhosa-speaking peoples. The various groups of Xhosa-speaking people seem to have gone out of their ways to accommodate and appease the colonists in hopes of being left in peace to continue their lives in the way they most wished to, and at every turn, they were frustrated by the demands of Britain and the colonists. They saw their land and cattle taken from them and even when they were innocent were accused of cattle rustling.

The cruelties visited on the Xhosa-speaking people were unbelievable. And yet they tried to maintain their dignity, to maintain as much of their customs and beliefs as they could in the face of the colonial and missionary onslaught. Their land they lost. As they said, “ilizwe lifile (the land is dead)” – “You kill our country by taking away our customs.”

So, as Mostert says, South Africa was born in a great tragedy, symbolised by the death of Sarili, who died in hiding at the age of 83, in 1893.

With the defeat of the amaZulu in neighbouring Natal the British had “achieved the military conquest of the two great black groups which had offered the main resistance to the white domination of South Africa.

In a final ironic twist of history, though, as Mostert noted, “It was through the Xhosa-speaking peoples, however, that African political leadership in South Africa mainly continued to express itself.” The list of 20th Century leaders who came from among the Xhosa-speaking peoples and have shaped the new democratic South Africa is impressive, among them Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Raymond Mhlaba, Wilton Mkwayi, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu, Steven Bantu Biko, Chris Hani, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, to name but a few.

Frontiers is an essential and absorbing read for anyone wishing to understand South Africa today, and an enjoyable trip through history, thanks to the skill of the author.

© Text copyright by Tony McGregor. All illustrations from the book Frontiers: the Epic of South Africa’s Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People by Noël Mostert (London, Pimlico, 1992).

[…] A book for all South Africans now is a post from: Tony McGregor […]