“The search for a sense of place in a city is also a search for that place where the city is most itself. For me this is Greenmarket Square.” – from Sea-Mountain, Fire City by Mike Nicol (Kwela Books, 2001)

For around three centuries the heart of Cape Town has beaten in Greenmarket Square.

It started in 1696 when the authorities at the tiny refreshment station, founded by the Dutch East India Company (or VOC, for Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) 44 years earlier, decided that a building should be erected for the Burgher (Citizen) Militia (or Burgher Wacht) which had been established in1659 as a force for both policing and defence.

The members of the militia were given wooden rattles which with they signalled the hours, as well as sounding a warning to loiterers and others up to no good.

Mothers in the Cape taught their children a little Dutch ditty:

Moederlief, ‘k geloof vast

Dat hy op de dieven past,

Goede klaper houdt de wacht;

Ik ga slapen – goede nacht.

(Dearest mother, I firmly believe

that he catches the thieves,

the watch has a good rattle

I’m to bed – good night)

The Burgherwacht Huys was built in 1696 on what was to become Greenmarket Square. It was a simple building and no doubt a fire-trap too! Fire was a constant hazard at the little settlement at the time and one of the duties of the Burgher Wacht was to act as a fire brigade.

In 1710 the Council of Policy, the highest authority at the Cape, decided to erect a more permanent building for the Wacht and in the same resolution set aside land for public use. The land so set aside was what is now Greenmarket Square.

The building for the Wachthuys was started in the same year. It served not only the Burgher Wacht but also served as a meeting place for the Burgher Council (Raad), until in 1755 it was demolished to make way for a new Wachthuys. The foundation stone of this new Wachthuys was laid by a member of the Court of Justice, Baerendt Artoijs, on 18 November 1755. The silver trowel used for the ceremony is still in the building.

The new building was completed in 1761, although it had been in use for some years before already. The façade, still largely unchanged to this day, was designed by Matthias Lotter whose father was a stucco-sculptor in Augsberg.

The balcony in the front of the building was used to make proclamations and citizens were summoned to the Square to hear these by a bell in a tower above the balcony, now replaced.

When in 1804 Cape Town was given a Coat of Arms, this was placed in the cartouche above the door to the balcony. From this time onwards the Wachthuys was used for civic functions, which is why it acquired the name the “Old Town House”. It served as Cape Town’s Town Hall until the present Town Hall was built in the early years of the 20th Century.

The square in front of the Old Town House was used as a market by the market gardeners on the outskirts of Cape Town, hence the name Greenmarket Square. The square was first mentioned officially in 1733 but by then had already been long in use.

The square was also a favourite gathering place for slaves during their infrequent free time, when they would gather there to gossip and relax. It was also popular with visitors from all over the world when their ships called at Cape Town, the square being a jolly meeting place offering travellers all the amenities of bed and board.

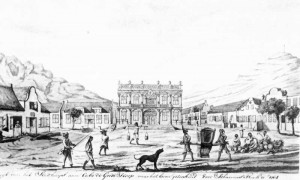

One of the travellers who spent time in the Square was Norwegian Johannes Rach who visited Cape Town in August 1762, staying for a fortnight. While in Cape Town Rach captured the early spirit of Greenmarket Square in a series of drawing like the one here.

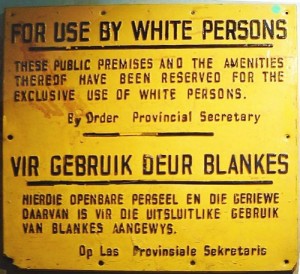

During the 1960s and 1970s Greenmarket Square entered into a period of what Nicol described as “sterility”, weighed down by the dark mantel of apartheid and its denial of life. It became primarily a car park.

One of the stories about the Square in that era concerns the farmer from the Free State Province who was visiting the Cape and had to make use of the toilet facilities in the Square. He found himself standing next to a coloured (creole) man at the urinal and was outraged. He wrote to the City Council demanding that the toilets be declared for white use only. The Council did a survey to establish who used the toilets most and found that coloured people were the most frequent users. They therefore decided to proclaim it a “coloured” facility.

The square and surrounding streets were paved with cobblestones in 1967 when the whole area was proclaimed a National Monument. This proclamation has ensured that the façades of the surrounding buildings will not be encroached on by high-rise buildings which would destroy the human scale of the Square.

In the late 1980s the Square was opened up for trading again and became a “noisy, friendly, raucous” place – it has become, as Nicol writes, “A meeting place again.”

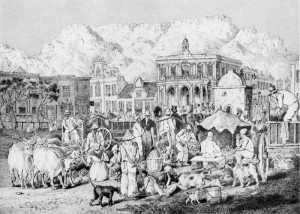

Nicol writes of the 1833 drawing of the Square and the Old Town House by Sir Charles D’Oyly shown here: “…the mountain rises behind Town House and the buildings that enclose the square in a warm embrace. I can stand where he stood, see the Town House he saw. I can imagine, then as now, disappearing into the market jostle, becoming part of the city.”

The Old Town House (centre) still keeps guard over the Square, while the Metropolitan Methodist Church (right) offers comfort to the lost and lonely, as it has done since 1879.