Jazz’s “annus mirabilis”

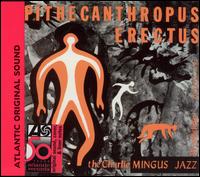

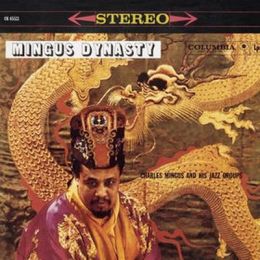

Mingus recorded four albums in this annus mirabilis of jazz: Mingus in Wonderland, a live album recorded on 16 January at Nonagon Art Gallery in New York City; Blues and Roots recorded on 4 February with Nesuhi Ertegun again doing the producing; and the two Teo Macero-produced albums Mingus Ah Um recorded in May and Mingus Dynasty recorded at the famous 30th Street Studio on 1 and 13 November, with different personnel on each day.

Blues and Roots and Mingus Ah Um stand out as works of art – albums that continue to shine, inspiring jazz musicians and fans 50 years later.

They are albums which show a musician reaching a pinnacle of creativity, and the wonder is that they are not the final words in this particular musician’s career – Mingus went on to make many more superlative albums. Somehow, though, these two are albums that fans and other musicians turn to again and again, they are both treasuries of great music that one can learn from and a great deal of fun to listen to.

Wonderland and blues

Mingus in Wonderland features John Handy on alto, Booker Ervin on tenor, Richard Wyands on piano, and Dannie Richmond on drums. Two of the tracks are songs that Mingus wrote for the John Cassavetes movie Shadows, namely “Nostalgia in Times Square” and “Alice’s Wonderland”. The other tracks are “I Can’t Get Started” and “No Private Income Blues”.

Mingus in Wonderland features John Handy on alto, Booker Ervin on tenor, Richard Wyands on piano, and Dannie Richmond on drums. Two of the tracks are songs that Mingus wrote for the John Cassavetes movie Shadows, namely “Nostalgia in Times Square” and “Alice’s Wonderland”. The other tracks are “I Can’t Get Started” and “No Private Income Blues”.

I have not been able to obtain a copy of this album and so cannot write with any certainty about it.

The album Blues and Roots is the subject of my article “Mingus gets down to the roots of the matter” and so I won’t describe it in any detail here. It was the first album on which Mingus’s composition “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting” appeared, a number which subsequently became something of a Mingus staple. This composition distilled the experiences Mingus had in the Holiness Church in his days in Watts.

Mingus Ah Um was the subject of my article “Mingus Magnificus Ah Um” and so again I will not describe it in any detail here. It introduced another Mingus staple, “Better Get It in Your Soul”, another feast of gospel and blues sounds. It also featured the song to which Mingus returned more than any other, the famous “Fables of Faubus” written in response to the attempt by Arkansas Governor Orval E. Faubus to prevent the integration of Little Rock High School in 1957. The lyrics, which included the words “Nazi Fascist supremists!” in reference to Faubus, were allegedly regarded as too extreme and not allowed on the album by the Columbia management.

Mingus Ah Um was the subject of my article “Mingus Magnificus Ah Um” and so again I will not describe it in any detail here. It introduced another Mingus staple, “Better Get It in Your Soul”, another feast of gospel and blues sounds. It also featured the song to which Mingus returned more than any other, the famous “Fables of Faubus” written in response to the attempt by Arkansas Governor Orval E. Faubus to prevent the integration of Little Rock High School in 1957. The lyrics, which included the words “Nazi Fascist supremists!” in reference to Faubus, were allegedly regarded as too extreme and not allowed on the album by the Columbia management.

Mingus Dynasty

The final 1959 album, also a Macero production, was Mingus Dynasty, which featured on the first date a line-up of 10 musicians including Mingus: Richard Williams on trumpet; Jimmy Knepper on trombone, John Handy on alto, Booker Ervin and Benny Golson on tenor, Jerome Richardson on baritone, Teddy Charles on vibes, Roland Hanna on piano and Dannie Richmond on drums.

On the first date the band recorded “Diane”, “Song with Orange”, “Gunslinging Bird”, “Far Wells, Mill Valley”, “New Now Know How” and “Strollin'”.

On the second date the musicians were Don Ellis on trumpet with Knepper, Handy, Ervin, Hanna and Richmond. They recorded “Slop”, “Put Me In That Dungeon” Mercer Ellington’s “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be”, and the Duke’s “Mood Indigo”.

On the second date the musicians were Don Ellis on trumpet with Knepper, Handy, Ervin, Hanna and Richmond. They recorded “Slop”, “Put Me In That Dungeon” Mercer Ellington’s “Things Ain’t What They Used To Be”, and the Duke’s “Mood Indigo”.

For me this last track is the pick of the album. It starts with a really slow introduction by the whole band with Mingus bowing his bass. Then Knepper enters with an incredibly soulful solo over the pizzicato bass. Then comes one of many abrupt tempo changes into double time. Then its abruptly back to a slow blues as Hanna takes over the solo spot to deliver a blues solo that is quite amazing, with another change to double time (punctuated by a “yeah” from Mingus) before he starts a brief solo which quickly moves into triple time – just unbelievably fleet by both Mingus and Hanna, and then it’s a tempo again as Mingus takes up the solo spot for a deep blues exploration with more abrupt tempo changes before Handy comes in to make his wailing solo and some great ensemble backing (with another shout by Mingus: “Early in the morning!”) to the end. Simply superb stuff!

Of the other tracks from the second date “Slop” and “Put Me In That Dungeon”are interesting, among other things, for the addition of two cellists to the line-up.

Apart from “Mood Indigo” the other outstanding tracks for me are “Gunslinging Bird” (Mingus’s tribute to Charlie Parker, originally called “If Charlie Parker were a gunslinger, there would be a whole lot of dead copycats”), “Slop” (a close cousin to “Better Git Hit in Your Soul”), “Song with Orange” (a great vehicle for solos by Handy and Knepper, with strong blues undertones), “Far Wells, Mill Valley” (after an almost atonal introduction, which has some echoes of “Some of My Favourite Things”, it continues interspersing some almost Oriental sounds with some straight-ahead jazz), and the short (too short?) blues “Put Me In That Dungeon” with its unusual voicings. I say “too short?” because it never seems to get going to the extent that it perhaps could if the musicians had a little more time.

Apart from “Mood Indigo” the other outstanding tracks for me are “Gunslinging Bird” (Mingus’s tribute to Charlie Parker, originally called “If Charlie Parker were a gunslinger, there would be a whole lot of dead copycats”), “Slop” (a close cousin to “Better Git Hit in Your Soul”), “Song with Orange” (a great vehicle for solos by Handy and Knepper, with strong blues undertones), “Far Wells, Mill Valley” (after an almost atonal introduction, which has some echoes of “Some of My Favourite Things”, it continues interspersing some almost Oriental sounds with some straight-ahead jazz), and the short (too short?) blues “Put Me In That Dungeon” with its unusual voicings. I say “too short?” because it never seems to get going to the extent that it perhaps could if the musicians had a little more time.

The final track is “Strolling” which is in fact “Nostalgia in Times Square” which Mingus wrote for the Cassavetes movie “Shadows” with words added, sung by Honey Gordon.

Mingus created music in this great year that has stood the test of time.

Don Heckma, in the Los Angeles Times of 11 February 2001, wrote the following paragraph which to me sums up why Mingus’s legacy is so enduring, and expecially the music he created in 1959:

“But it was probably his passionate intensity, a drive to transform his visionary ideas into the hard facts of performance reality, that made his music such an extraordinary combination of accessible melody, driving rhythms and insistent social statement. His live performances were often delivered in chaotic settings, but they were never dull. And his recordings could easily serve as the passionately interactive soundtrack for the unfolding civil rights developments of the ’50s and ’60s.”