A historical investigation into the Sea Point beachfront as a public open space throughout the 20th century with special reference to memories of growing up along the Sea Point Promenade by Leila Emdon.

Chapter Two continued – The growth of a suburb: the Development of Sea Point in the late 19th century to the 1950s

<< previous World War Two and Sea Point

The Exclusive Utopia of Sea Point- Sea Point and Apartheid

The Sea Point promenade was a safe and clean environment where the community made use of all the public facilities. After 1948, this was to become exclusively reserved for whites only.

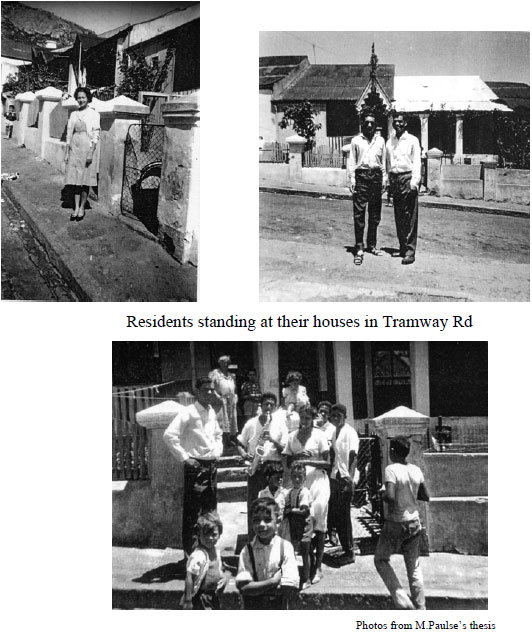

Sea Point was always a largely white suburb, an upper class suburb as well. However, living in Tramway Road and Ilford Street was a small coloured community. “In the late 19th century, British ideas on housing workers to promote economic production influenced on the elite of Cape Town, the capital of the British Colony. In the interest of the economic production of the Green and Sea Point Tramway Company, employers who began their work day at the Sea Point terminus were to live in cottages at the Sea Point station.”42 Coloured women became domestic servants and washerwomen in the area, and the men served at the Tramway company or held working class positions in the area. Their houses were small and overcrowded, as well as dilapidated. The children could not attend the schools nearby and their houses were separated from the rest of Sea Point, so as “not to disturb the belief that the municipality belonged to a wealthy class.”43

During the earliest years of Apartheid, 1949-1953, the National Party passed racebased laws that intensified restrictions to social and political life. “Apartheid legislation intensified the radicalisation of space in the country and bestowed upon white people greater privileges then before.”44 “Demarcated space informed race identity, stimulated feelings of marginalisation, provoked agency and encouraged compliance.”45 The Sea Shore Act of 1935 obliged residents of the city to bathe in racially separate bathing areas. During the 1940s whites and blacks swam in different municipal swimming baths and the main beaches were segregated. Segregated bathing, however, had long been practised in Sea Point. By 1913, whites patronised the Sea Point Pavilion and around 1917 the city constructed a bathing pool, the ‘Non- European Pavilion’, for coloureds near Queens beach near the Sea Point railway station. While the naming of the Pavilion for whites both identified whites with the suburb and reinforced the notion of the suburb as a space for white people, the naming of the recreational site for coloureds emphasised the marginalisation of coloureds in Sea Point.46 The coloured residents of the area could only enter the Pavilion if they were a servant of a white family or were doing work in the Pavilion.

The beachfront and the promenade is a beautiful place, but in this golden era one can also argue that, it was also a ‘golden bubble’. People were isolated from poverty, and given the privilege of the space because they were white. However, the white residents that I interviewed made aware to me that although they enjoyed the privileged they were aware of the exclusion. “The beaches were the same except it was strictly demarcated for whites only. Then they built a fence, halfway down they road and had the coloureds on the one side and the whites on the other side, on the beach. There was a huge outcry and they broke the fence down. Milton pool was exactly the same, even broken baths.”47

“When I hear (racist people) how biased they are, I think, “what right have you got?” There are books written now about what we saw in the Apartheid and we closed our eyes to it. There was nothing we could do about it or we would go to Jail. Why did they break down District Six? They were frightened; the Nationalists were frightened that there were too many coloureds living so close to the city. Therefore, they threw them out to Atlantis and other places. It was terrible and there was nothing you could do about it.”48

Sandra also describes how her family was always aware of Apartheid. She also lived close to Tramway road and knew the people. “I lived near Quendon road which was near Queens’s road and there was a coloured township nearby called Tramway Road. I feel very sad about Tramway road. In the 1990s, the people were supposed to have their land back but many did not reclaim it and now it is overgrown. As a child these coloured families lived there, we shared a wall. I used to climb up a ladder go over the wall, through their little lanes to get to school. It was safe. They were a wonderful community.”49 Both Sonia and Sheila also remember Tramway road and were aware of the exclusion they experienced about the apartheid. Residents that I have interviewed do not adopt a racist attitude but more one that resembles a Cape Liberal tradition. They were against Apartheid. While some did what they could to support the resistance, others realised that unless you were willing to fight, not much could be done.

42 M, Paulse, 2002, An Oral History of Tramway Road and Ilford Street, Sea Point, 1930s-2001: The Production of Place by Race, Class and Gender, University of Cape Town thesis collection, pg 36

43 ibid

44 ibid pg 124

45 ibid

46 ibid pg 124

47 Joe Maureberger, 31st August 2008, recorded interview

48 ibid

49 Sandra Sheinbar, 31st August 2008, recorded interview

<< previous World War Two and Sea Point —- Sea Point from 1960s-1980s next >>