The Wild Coast

The Transkei Wild Coast is a scenic wonderland of unspoilt beaches, gently rolling hills covered with lush green grass interspersed with some rugged ravines, dramatic cliff faces topped with wild banana trees with ferns growing out of the cracks in the rocks.

In summer the Wild Coast is a hot, moist stub-tropical area with mists that roll over the hills and make one’s skin damp, the leaves of trees drip and animals almost disappear on the roads, creating real hazards for drivers.

This is the region my first wife Joan (we had been married a year then) set off for from Durban in our hired car in the middle of December 1970 for a holiday with my parents and my brother Chris and his wife Maxine and their three-year-old daughter Andromeda (known as Meda). We were then living in Durban.

Lovely beyond any singing of it

The drive down to the Wild Coast was uneventful and the scenery quite beautiful, as it is at that time of year. Natal and the former Transkei are very similar across either side of the border between them.

As we drove through the little town of Ixopo on the kwa-Zulu Natal side of the border we were reminded of the wonderful opening sentences of Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country : “There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hill are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond any singing of it.”

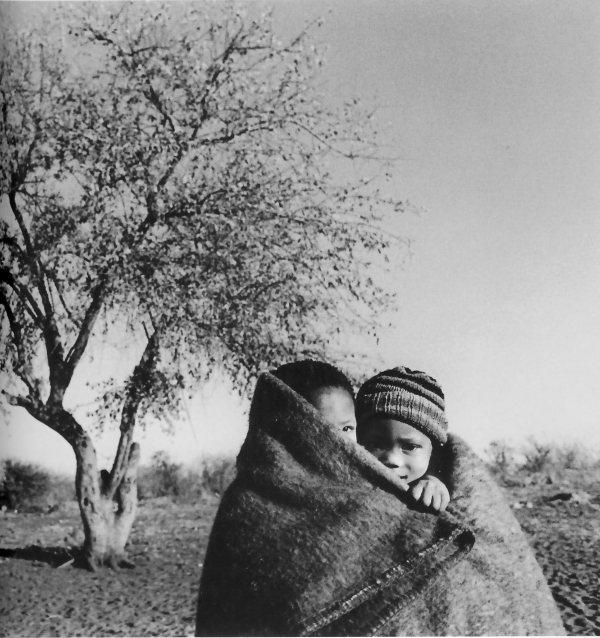

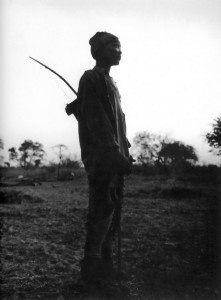

We drove along many such roads, past many such grass-covered and rolling hills, with the huts of the people and their goats and sheep and large black pigs, their cattle and stands of maize. It was a beautiful journey with a beautiful destination.

At that time I did not have a great camera, but I took photos anyway and whenever I could to try to capture the loveliness of the scenery and its people. The accompanying photos were all taken on this magical holiday, which was the last time we were all together as a family until my parents celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1985, so it is a special time in my memory.

The cottage at the sea

We arrived at my parent’s little cottage at Qolora Mouth in the late afternoon and it was a time of first meetings – Joan and I had not met Maxine or Andromeda before, and Joan had not met Chris either. My parents had brought Joan’s mother from East London to join us. So it was a happy time, as I guess Christmas is supposed to be.

Our days at Qolora were peaceful, spent in long walks on the beach and the occasional dips in the warm Indian Ocean.

Due to the legislation governing the so-called “Bantu reserves” under the apartheid regime, white people were not allowed to own property but could get permission from the local chief to build and occupy beach cottages. So the cottage my parents had was not strictly theirs. They were allowed to take holidays there only. So there was no incentive to “improve” these cottages in any way.

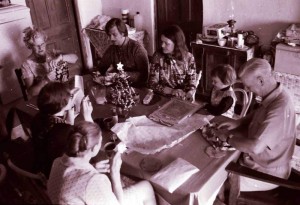

As a consequence this cottage had no running water or electricity. Water was collected from a little spring that flowed, winter and summer, with the sweetest, freshest water imaginable, just behind the cottage. At night we played canasta or read by the light of candles and paraffin lamps.

The cottage itself had two bedrooms on either side of the little living room, and a small kitchen at the back. On either side of the front stoop (verandah) were two thatched huts, in  one of which Joan and I slept and in the other Chris, Maxine and Andromeda. Joan’s mother had one room in the cottage and my parents the other.

one of which Joan and I slept and in the other Chris, Maxine and Andromeda. Joan’s mother had one room in the cottage and my parents the other.

On Christmas day the Anglican priest from Butterworth, whom we knew well, Fr Woods, came to celebrate a Christmas mass to which some of us went.

Christmas and New Year

Christmas lunch was a happy time with presents all round and of course wonderful food. My mother was especially good at making steamed Christmas pudding, something of an anomaly in the hot summer weather, but enjoyable nonetheless.

Christmas lunch was a happy time with presents all round and of course wonderful food. My mother was especially good at making steamed Christmas pudding, something of an anomaly in the hot summer weather, but enjoyable nonetheless.

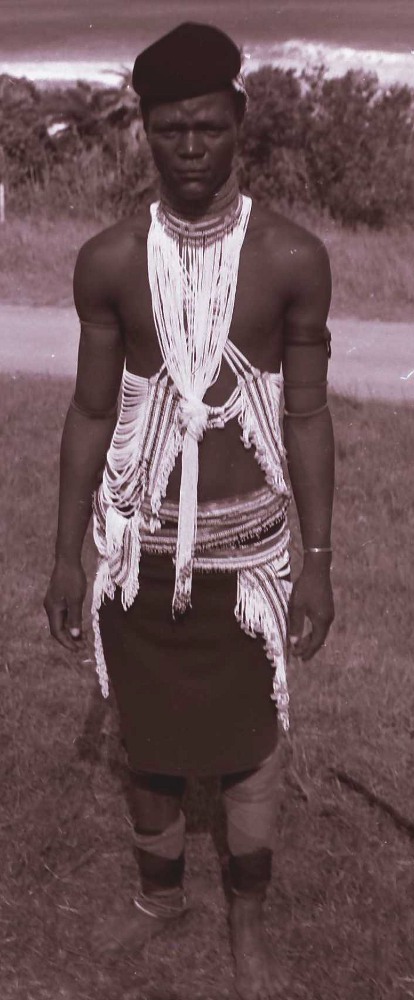

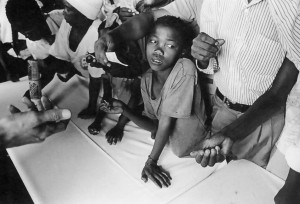

On New Year’s Day a group of local people came around looking for the traditional

“Christmas Box” and so we were entertained by their singing and dancing.

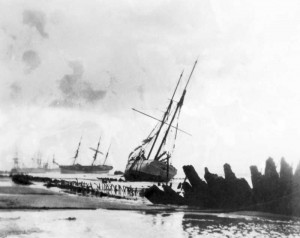

The “Wild Coast” did not get that name for nothing! Historically it was a wild place, where the seafarers of old feared the rocks and contrary currents and winds. Many a ship came to grief on the treacherous rocks that stick out into the ocean along its shoreline. There are many stories of the survivors of shipwrecks being taken care of by the local people.

But for us that December it was the setting for an idyllic time of relaxation and fun, of getting to know each other anew, of celebration.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2012

From Apartheid to Zaamheid – a book review

From Apartheid to Zaamheid is a readable and practical book about making a difference, being a positive force for change in South Africa, rather than a perpetual whinger about all that is wrong in the country.

My only complaint really is, why did the book take so long to arrive on my desk? It was published by Aardvark Press in 2004 and yet I only came to see it this week. Well, maybe I’m not as awake as I like to think I am!

The author is Advocate Neville Melville who played a significant role in the transition from the apartheid regime to the non-racial democracy we live in today. He has also been the Banking Ombudsman as well as being appointed by former president Nelson Mandela as the Police Ombudsman.

The book is 130 pages long and presents, in very readable ways, the problems facing South Africa and a number of possible ways that individuals can make contributions to solving these problems – not in grand, sweeping ways, but in small ways that touch people’s lives.

The word “Zaamheid”, Melville explains, he coined from the international symbol for South Africa, namely “ZA”, and the initial letters of the words “alle mense (all people)” to form the “Zaam”, which sounds a lot like the Afrikaans word “saam” which means “together”. The suffix “-heid” means roughly “-ness” as in “apart-ness”.

Melville defines his new word as meaning “everyone working together” and he writes, “The choice of an Afrikaans-sounding word would, in itself, be an act of bridge building.”

That introduces the major theme of the book, which is also its sub-title: “Breaking down walls and building bridges in South African society.”

Some of the chapter titles give an idea of how this theme is explored by Melville: “The crack in the wall”; “The great wall”; “Behind high

In his analysis of the problems facing South Africa Melville makes it clear that the walls, both real and metaphorical, which continue to keep South Africans apart from each other are the source of the ills besetting the country: “The affluent continue to barricade themselves from the rest of the world in security villages with checkpoint controls. The workplace is increasingly becoming a no-go zone for whites, particularly if they are males.”

In the final chapter of the book, “The way ahead”, Melville makes some pertinent points, like “We are, as a country, spending too much of our energies in trading blame and squabbling amongst ourselves. Instead we should be focussing all our efforts into the challenges that face us. Until every last person has a stake in the country’s wealth, none of our individual wealth is secure.”

The book as a whole is a challenge to all South Africans to become bridge builders rather than wall builders.