Introduction

South African jazz started not long after the great explosion of the music in New Orleans more than 100 years ago – or it started long before then, depending on how you look at it.

“Almost as soon as jazz went on record in America, in the early decades of the twentieth century, those wax impressions arrived in South Africa. They landed on fertile ground, for South Africans had a rich and dynamic musical culture of their own, into which they had already drawn aspects of earlier and parallel African-American musics.” – from Gwen Ansell’s lovely book Soweto Blues (Continuum, 2004).

The rhythms and sounds of African traditional music are of course the well-spring of jazz, taken to the “New World” in the cruel holds of slave ships. The music of Africa, far from being “primitive” or simple, is in fact a highly complex music, with sophisticated harmonic and rhythmic structures which, when combined with elements from western composed and folk musics, grew into the music which, for all its variety and rich diversity, we tend to lump together under the not-so-elegant term “jazz.”

In South Africa, of course, these African sources and influences are far more directly audible. The music of Africa which we encounter in South Africa comes from many different ethnic sources, Khoisan, Xhosa, Zulu, Sotho, Tswana, Venda and many others. Each has given a particular flavour to the music of South Africa.

The Xhosa contribution

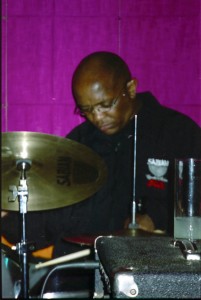

Lulu Gontsana who played in the band “Xhosa Nostra” (among many others). Here he is with the Zim Ngqawana Quartet

To take just one example of the richness of roots of African music, musicologist Dave Dargie in his outstanding book Xhosa Music (David Philip, 1988) speaks of the complexity of rhythmic structure of Xhosa songs: “It is the combination or multiplication of rhythms which brings the body to life in the song.” Of the harmonic richness of the songs he writes: “Some songs are particularly rich in vocal parts, with over thirty or even more parts being sung at the same time if there are enough singers.” He points out that “it is highly unlikely that any song will be sung in exactly the same way twice.” Sounds like jazz to me!

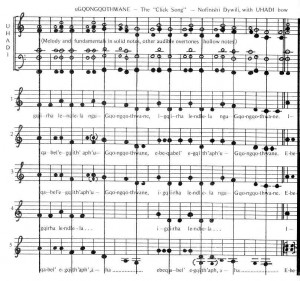

A Xhosa song which achieved world-wide fame is the so-called “Click Song” popularised by Miriam Makeba. The traditional (or accepted canon) song on which this is based is the song “uGqongqothwane”, the name the amaXhosa call the dung beetle. The name is onomatopoeic, mimicking the knocking sound the beetle makes on hard surfaces, the “q” being pronounced as a “click” produced by creating a vacuum behind the tongue against the palate and then releasing the tongue with a sudden jerk to produce that click, much as people would make the sound of horse’s hooves on a hard road surface. The “g” in front of the”q” serves to accentuate the click, making it harder.

The transcription shown here is by Dave Dargie of “uGqongqothwane” as played on the uhadi bow by the late Nofinishi Dywali, a traditional musician who collaborated with Dargie in his research.

Considering the sophistication and complexity of Xhosa music it might be no surprise to discover that a great number of South African jazz musicians came from that ethnic group. Indeed there was in the 1980s a group of Xhosa jazzmen who called themselves the “Xhosa Nostra”!

Cape jazz – what is it?

But jazzmen in South Africa have come from all ethnic groups in the country. Jazz is a music that doesn’t know boundaries of race, even though it grew out of the black experience.

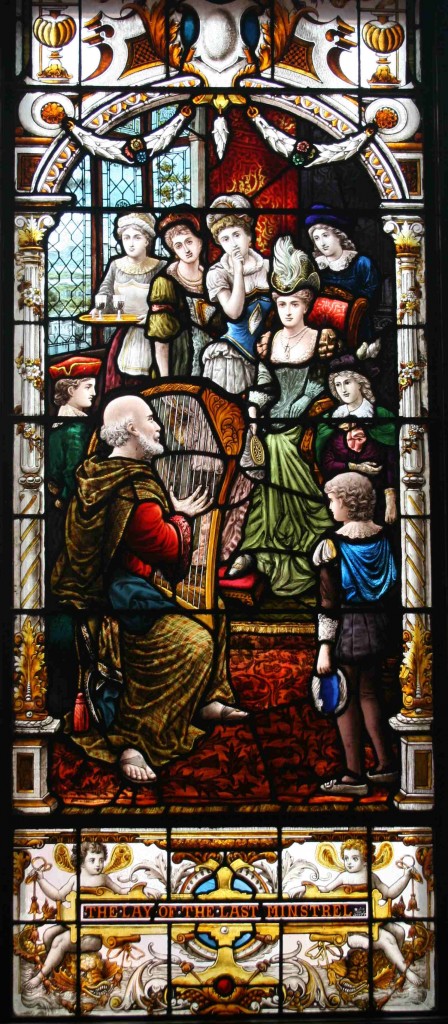

The rich cultural heritage of the indigenous people was added to by the influx of slaves into the Cape Colony, which, like the slaves which were taken to the Americas, brought their own musical traditions with them, traditions which soon were part of the great cultural melting pot of South African music. So in the music of the Cape, which is often called “Cape Jazz”, can be heard the influences of Khoi-khoi and San music intertwined with the melismatic styles which came from Malaysia and Indonesia and the rhythms and harmonies of the amaXhosa who came to the Cape in search of work in the 19th Century.

The rich diversity of jazz in the Cape is emphasised by Cape Town musician the late Vincent Kolbe in an interview with jazz expert Colin Miller, who, in his article “What is Cape Jazz,” quotes Kolbe at length:

“Now naturally you hear a lot of music. You learn to dance, you listen tentatively to the music; you listen to the rhythm, and you listen to things that encourage you to move. So you become sensitive to music. You also go to church. And there’s the organ grinding away and the hymns of all the ages and chants. And then Christmas! But on your way home from school, there’s a Malay choir practising ‘Roosa’ next door and there is even African migrants living in a kraal nearby singing Xhosa songs or hymns or something and you could have the Eoan Group practising opera at the church. Then there’s the radio and the movies. And you see this man conducting and his hair flowing in his face so naturally you go and fetch your granny’s knitting needles and you let your hair fall over the face and you conduct. So that’s the whole thing, movement and dance and imitation and living it.”

The marabi foundation

“I’ve always loved trains. And marabi music for me always seemed to have that same quality as the sound of a train: it just goes on and on, but as it goes on it always changes and you know it’s going somewhere.” Trombonist Jasper Cook who played with the African Jazz Pioneers, as quoted in Ansell, Soweto Blues.

In his indispensable introduction to the history of jazz in South Africa, Marabi Nights (Ravan Press, 1993), Professor Chris Ballantine notes: “If there is one concept which is fundamental to any understanding of urban black popular music in South Africa, it is that this music is a fusion – vital, creative, ever-changing – of traditional styles with imported ones, wrought by people of colour out of the long, bitter experience of colonisation and exploitation.”

The “marabi” of Ballantine’s title is an important concept to understand in order to get an full appreciation of South African jazz and its history. Marabi was a “style forged principally by unschooled keyboard players who were notoriously part of the culture and economy of the illegal slumyard liquor dens” which were part of every black township in the early part of the 20th Century. One can hear some echoes of the birth of jazz in New Orleans here, perhaps?

Ballantine continues his exposition on marabi and its importance to South African jazz:

“A rhythmically propulsive dance music, marabi drew its melodic inspiration eclectically from a wide variety of sources, while harmonically it rested – as did the blues – upon an endlessly repeating chord sequence. The comparison is apt: though not directly related to the blues, marabi was as seminal to South African popular music as the blues was to American. (The cyclical nature of each, incidentally, betrays roots deep in indigenous African musics.)”

In the late 1920s and early 1930s black musicians started to incorporate the sounds of the big bands from the US swing era into their marabi-based music, and the dance craze took off in the townships – marabi music played in swing style. A number of early African jazz bands started to flourish, building sizeable followings in the townships and even beyond. Their names have become iconic in the story of South African jazz – the Jazz Maniacs, the Merry Blackbirds, the Rhythm Kings, the Jazz Revellers, and the Harlem (yes, indeed!) Swingsters.

The leader of the Merry Blackbirds was Peter Rezant, and his name is still revered by musicians. His band had the edge over many of the others because all of his players were schooled, and could read music. The Merry Blackbirds even played to white audiences in Johannesburg before apartheid made this impossible.

Now and into the future

While Johannesburg on the Witwatersrand had the edge in terms of the number of people there looking for entertainment that could be provided by jazz musicians, a little town in the Eastern Cape also achieved renown as the “Little Jazz City” because of the thriving jazz scene there and the number of influential and famous musicians who came from there. This was Queenstown, at one time the centre of the wool trade in the Eastern Cape and a thriving centre from which wool was transported to the ports for export. Jazz fans in Queenstown had a reputation for being highly critical and knowledgeable about the music.

Jazz was, and still is, played and enjoyed in all the major centres in South Africa, though it has two centres of gravity, as it were: Cape Town and Johannesburg. But players and fans can be found in every corner of this great land.

There were a number of jazz musicians who left South Africa during the apartheid era because the tension between the freedom demanded by the music and the oppression of the regime was too great to bear. Many of these great musicians died in exile, and South Africa is considerably the poorer for having lost these great souls. Some did return to further enrich the great mix that is South African jazz today.

And many brave ones managed to keep the faith and the music alive in South Africa through those dark and turbulent years.

There is now a new generation of jazz musicians building on the deep heritage of the music in South Africa. There is Paul Hanmer who brings a new, almost cross-national flair to the music, with strong classical ties. There is Carlo Mombelli with deep roots in the avant garde European jazz scene and equally deep roots in South African music. There are the young musicians like Marcus Wyatt delving into the roots and coming up with fresh ideas and sounds.

So jazz is unlikely to die anytime soon. Though of course it is a living music and so is always changing, always finding new sounds and ways of doing things.

And that’s great by me – I love it all.

© Text and photos copyright Tony McGregor