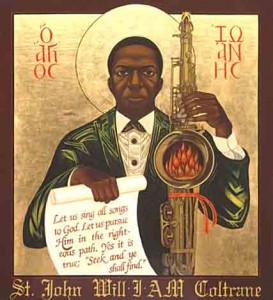

Many jazz musicians have been devoutly religious, but only one has been canonised – Saint John Will-I-Am Coltrane, who would have turned 85 on 23 September 2011.

The influential tenor player was born in Hamlet, North Carolina, in middle class circumstances into a family with deep religious roots.

He started playing other instruments, especially alto, only gravitating to the tenor sax after playing alto with Dizzy Gillespie’s Big Band until that broke up. After that Coltrane stayed with Gillespie’s small group and took up tenor.

One of the big breaks in his career came in 1955 when he was called by Miles Davis to join the trumpeter’s famous “First Great Quintet” in the place vacated by Sonny Rollins. Miles at that time was exploring modal scales which had a great impact on Coltrane. Valerie Wilmer in her book about the “New Music” As Serious as Your Life (Serpent’s Tail,1992) wrote that Coltrane had said “…he used to listen to Miles Davis on record and fantasise about playing tenor the way he played trumpet.”

Coltrane was with the Davis group until November 1956 when he rather abruptly left it. He was by this time being badly affected by heavy drinking and his addiction to heroin. In his biography of Davis (Paladin, 1984) Ian Carr writes “Miles may have tried to jolt the saxophonist from time to time to sting him into revolting against the inexorable progress of his destructive habit.” Whatever the reason or process of his leaving the Davis band Coltrane went home to Philadelphia where he managed to clean himself up, kicking the heroin habit cold turkey and having a kind of spiritual awakening with the support of his first wife Naima.

In the liner notes to his great album, A Love Supreme, Coltrane wrote about this episode:

“During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.”

In early 1957 Coltrane was offered a recording contract by Bob Weinstock of Prestige Records which led to the saxophonist’s first recording date as a leader. Recorded at the end of May 1957 it was released as Coltrane in 1957.

Coltrane’s second solo album was Blue Train issued by Blue Note records in 1957 which featured four of Coltrane’s own compositions and one standard.

Coltrane’s second solo album was Blue Train issued by Blue Note records in 1957 which featured four of Coltrane’s own compositions and one standard.

By January 1958 Coltrane was back with Davis after a six-month stint with the Thelonius Monk Quartet which produced two outstanding albums: Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane and an outstanding date at Carnegie Hall, the recording of which was only discovered serendipitously in 2005 and released as Thelonius Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall. Of great interest in the first of these albums is the contrast between an earlier influential tenor player, Coleman Hawkins, who plays on two of the tracks, and his younger counterpart Coltrane.

Wilmer wrote about Coltrane’s technique and musicianship: “Coltrane rewrote the method book for the saxophone, just as Charlie Parker had done twenty years earlier and Coleman Hawkins twenty years before that.”

In 1959 Coltrane was an influential part of the Davis group which made the seminal Kind of Blue album which has become something of a jazz classic, very possibly the top selling jazz album of all time. This session confirmed Coltrane’s interest in modal jazz and set him off on his explorations of other musics, especially African and Indian.

Shortly after completing the Kind of Blue recording was Davis, Coltrane was again in studio as leader to record the first album consisting entirely of his own compositions, Giant Steps, a breakthrough album which showed to the full his playing style dubbed “sheets of sound” by critic Ira Gitler. The complex chord sequences of the title track have been called “Coltrane changes”.

Shortly after completing the Kind of Blue recording was Davis, Coltrane was again in studio as leader to record the first album consisting entirely of his own compositions, Giant Steps, a breakthrough album which showed to the full his playing style dubbed “sheets of sound” by critic Ira Gitler. The complex chord sequences of the title track have been called “Coltrane changes”.

By the time of his recording of the album My Favorite Things in 1961 Coltrane was heavily into his exploratory phase, in part as a result of meeting and studying with famed sitar player Ravi Shankar. Coltrane used a soprano sax on this recording for the first time.

By the time of his recording of the album My Favorite Things in 1961 Coltrane was heavily into his exploratory phase, in part as a result of meeting and studying with famed sitar player Ravi Shankar. Coltrane used a soprano sax on this recording for the first time.

After some personnel changes the so-called “Classic Quartet” was in place by 1962. This group consisted of pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison with Elvin Jones on drums.

The Classic Quartet produced increasingly inventive albums, including what is considered by most to be Coltrane’s greatest, A Love Supreme. This 1964 album indicated the increasingly spiritual direction Coltrane was taking. In the liner notes of the 1995 re-release Michael Cuscuna, prolific producer and discographer, wrote: “A Love Supreme is one of the most honest musical performances put to tape. Its beauty and appeal are timeless.”

A Love Supreme has gone on to influence many generations of musicians and fans, in a way as Kind of Blue has done, who would not normally be associated with jazz.

A Love Supreme has gone on to influence many generations of musicians and fans, in a way as Kind of Blue has done, who would not normally be associated with jazz.

By the time Coltrane died in July 1967 he was a legend with a huge number of high quality recordings to his name. Valerie Wilmer wrote, “In addition to his musical importance, Coltrane exerted a profound spiritual influence on the musicians who followed in his footsteps.”

“What he did through his own example, was to give not only the musicians but the Black community as a whole, an example by which they could live,” Wilmer continued. Which is why, perhaps, he was canonised by the African Orthodox Church back in the early 1980s.

As the founder of the St John Will-I-Am Coltrane Church in San Francisco, Franzo Wayne King, said in a sermon reported by the New York Times in 2007: “The kind of music you listen to is the person you become. When you listen to John Coltrane, you become a disciple of the anointed of God.”

I do wonder what Coltrane himself would think of this, seeing that he was determinedly non-denominational?

But the influence for positive, good values is clear.

Coltrane said in 1966: “I hope whoever is out there listening, they enjoy it.” Thank you, St John, we do!