Public spaces in cities usually attract interesting characters – especially if the spaces are also tourist attractions.

Church Square in Pretoria is no exception – and has the added characteristic that it is a favourite gathering place for the start of protest marches and trade union demonstrations.

On the morning when I went there to take the photos accompanying this article I immediately noticed two people holding a pigeon, of which there are thousands in the Square, and bending over this bird with an intensity that immediately made me curious.

I went over to see what they were up to and found that they were, with great patience and care, removing some cotton that had gotten wound around the poor bird’s legs.

“It will lose the leg if this cotton stays on it,” explained Vincent, one of the two men. Meanwhile the other man, Chicco, was doing the “surgery” to remove the cotton – and indeed I could see that the leg was already in rather poor shape because of the cotton which had made quite deep indentations in each leg, just above the feet.

It turned out that Vincent and Chicco were flower sellers, with a stand at the western entrance to the square. Their bunches of flowers around the pylons at the western entrance made a colourful and fragrant display.

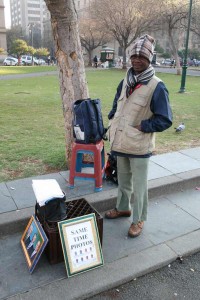

A little further I came across a man with a sign leaning against a plastic bottle crate reading “Same Time Photos” and I noticed on his sleeveless jacket an insignia: “Freelance Photographer.” Intrigued, I introduced myself to him and we got chatting. His name is Phala and his studio is under one of the trees on the square. He noticed that my camera is a Canon and proudly showed me his – also a Canon!

All the while the sound of a “vuvuzela” was blaring hoarsely over the square. The sound was coming from a group of members of the South African Municipal Workers’ Union standing in front of the Old Raadzaal waiting for their comrades to begin a march to the municipal offices down Vermeulen Street, some of whom were attracting attention to their cause by blowing their vuvuzelas.

Along the paths crossing the square were people of all walks of life, some hurrying, not doubt to offices, others strolling, no doubt waiting for something else to happen.

In the middle of the square Old Oom Paul (better known outside of South Africa as Paul Kruger, formerly the President of the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) when the Anglo-Boer War broke out in 1899) stands darkly brooding over Pretoria’s central Church Square, with his top hat often providing a useful perch for pigeons.

The statue of Oom Paul was sculptured by renowned South African artist Anton van Wouw (1862 – 1945) and was first erected in Pretoria West, then moved to a position in front of the Pretoria Railway Station before being placed in its present position in 1954.

The name “Church Square” is derived from the fact that, on the very spot where Oom Paul now stands brooding there was a church – in fact three churches were sequentially built on that spot, the first in 1857, the last demolished in 1905.

The particular character of Church Square also derives from the series of interesting and mostly quite old buildings which surround it.

One of the most impressive is the Raadzaal on the south side of the square, built to house the Volksraad (Parliament) of the ZAR. It was designed by Sytze Wopke Wierda, who had been brought from Holland to the ZAR by Kruger as Government Engineer and Architect in 1887, and who was responsible for a number of other buildings in Pretoria, including the Palace of Justice which stands facing the Raadzaal across Church Square..

The building is in an Italian Renaissance style with a figure said to be of Athena at the top of the tower which dominates the roof line. The Volksraad first met in this building in May 1890.

The Palace of Justice has twin towers and a semi-basement housing cells. The most famous trial held there was the so-called “Rivonia Trial” of 1963/4 in which Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela and nine of his comrades stood accused of sabotage and which led to their incarceration on Robben Island off Cape Town until 1989 and 1990.

Also on the north side of the square is the Herbert Baker-designed Reserve Bank which pre-figured his later design for the Union Buildings.

To the east of the square is the interesting Tudor Towers built in 1904 by tycoon George Heys, who had the famous Melrose House built for his family. This building housed his offices as well as other businesses owned by him.

On the other side of the square are the jugendstil Café Riche building and the General Post Office.

© Text and photos copyright Tony McGregor 2011